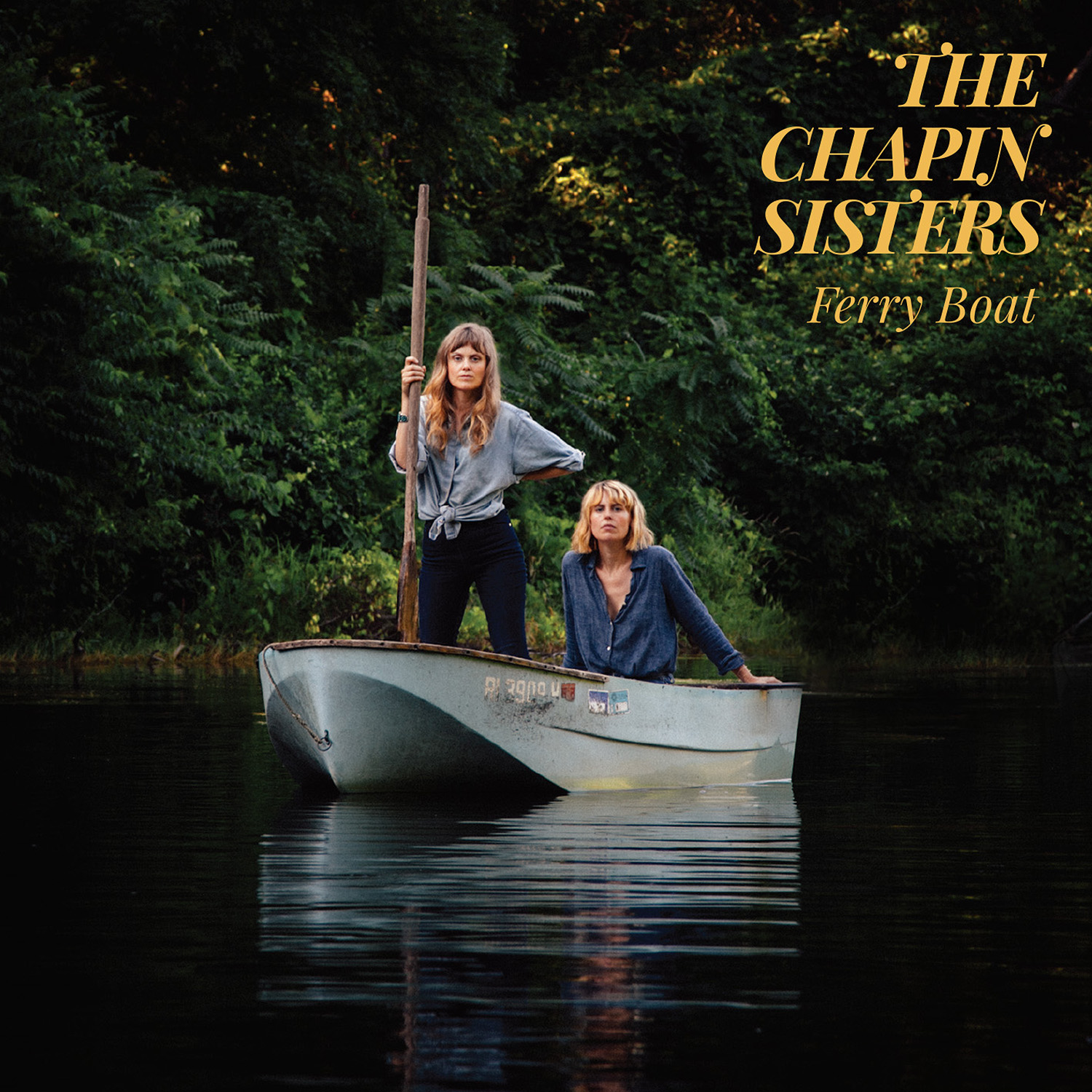

Ferry Boat: A Conversation With The Chapin Sisters

A Conversation with the Chapin Sisters, Abigail and Lily

Mike Ragogna: It is so great to talk to you ladies again! So your new EP Ferry Boat is somewhat inspired by current American politics, although it’s not overtly discussed in the work. Did they affect the writing process?

Abigail Chapin: The songs were written mostly before the election…

Lily Chapin: …although not a hundred percent. We finished them all after the election.

MR: So the creative process started before the election, but might it have affected the song reads, maybe causing some lyrical tweaks?

AC: We were working on the songs leading up to the election, which was a very dramatic time. We had also just both had babies about six months before. Those things, politics and our new roles in life, were very much in the mix. We knew we were going to the studio the third week in November, just a week after the election. When we were actually recording the songs and finalizing arrangements and lyrics, we were very affected by that. That is why the content of the material is not written as a reaction to the election; it’s just that there was no way to separate songs about anything from politics. Everything is tied up together. We were very shocked and outraged and heartbroken at the moment. Some of these songs are about heartbreak of another kind, but it didn’t hurt the performance. I think it helped the performance to really feel the heartbreak about something totally macro instead of micro.

MR: To me, songs like “Lost,” if it weren’t directly related to the 2016 election, it did feel like it had the undertones of an “Oh my God!” moment.

LC: Yeah, that’s true.

AC: That’s the last song that got written.

LC: We were changing and adapting the lyrics, really, up until the last minute.

AC: I have an anecdote about that song that I remember. We write most of our songs together but that one was more of a Lily song. Lily’s the one who sings it. I do remember when we were finalizing lyrics, she said, ”You were leaning in, pushing too hard, running the yard. It’s like Hillary! She was pushing so hard, it was too hard, women are never allowed to…”

LC: …the “leaning in” lyric definitely was put in as a reference to the Sheryl Sandberg book, the crazy controversy of that moment in culture where everybody said, “You have to read this book! It’s the best book ever,” and then everybody said, “It’s the worst book ever!” There was so much controversy about the right way to be a feminist and the wrong way to be a feminist and the right way to be aggressive if you’re a woman and the wrong way to be aggressive and the ways women talk to each other about these things. Then there’s this other idea about being too passive and how maybe you’re sleeping in and just kind of giving up. These are definitely personal thoughts, too, about my own life and our own lives as women, but they certainly do feel appropriate at that moment. What we were facing politically was quite a crisis in female identity for sure.

MR: And this happened before the “Me Too” movement. This has been a problem in the culture for so long and people weren’t speaking up about it, or when they did, they were dismissed or trivialized. Do you feel like things have changed since you were having those sort of polite discussions of what was going on in the culture then versus now, in 2018, when there’s so much more of a focus on women’s issues?

AC: I’d just like to say I don’t know that people weren’t speaking up about their experiences. I think for whatever reason, this time, it feels like suddenly everybody cares. Women have known this has been part of everyone’s daily lives for time immemorial. I don’t think it was that women weren’t speaking up, it’s just the culture at large was either taking it for granted and saying, “Yeah, boys will be boys. Women, it’s just part of being a strong woman. You just have to deal with it. It’s flattering.” Suddenly, for whatever reason, we’re at a moment where there’s outrage about it. I think that’s almost the more shocking part. Everyone’s known about this forever. It’s interesting that suddenly people care—people being men or just the culture at large. Suddenly, it’s a conversation. Definitely, at the very least, what has changed is that it’s cool to talk about it now. It’s definitely a talking point that everyone’s interested in. Before it felt a little like it was easy to be seen as a boring feminist who just wanted to talk about women’s issues, and that wasn’t cool.

LC: It was seen as a niche issue.

AC: Exactly. Somehow women—fifty percent of the population—were seen as a minority; a small subset. It’s like how if you play one woman band per hour that’s enough.

MR: Is it possible the timing also was right because of a reaction to the extremes of Trump years? Everything seems like it’s getting unearthed about, well, everything now.

LC: I would say it was the low point of public perception based on the fact that we just elected someone into office who’s a multiply-accused sexual assault perpetrator. I think the outrage was warranted and it was a symptom of a real crisis. The crisis goes beyond women’s issues or any type of political subgroup; it’s a crisis of our democracy, really. It’s a crisis of who is our leader, morally, ethically and professionally. If our system is so broken that we’ll elect a person who is so overtly under-qualified for an office over his opponent and one of the main reasons that seems to have occurred because of some people’s biases toward another person’s gender; that is an issue. So saying, “Oh, it was the perfect moment, all of these things came together,” makes it seems like it was an opportunity, and I think people have turned it into an opportunity out of despair over what a crisis it was. I think that’s the only thing you can really do when you’re faced with a wall coming at you is fight it. I don’t necessarily think of it as an opportunity so much as a crisis that needs to be faced head on. As a woman who went through high school in the late nineties in a suburb of New York City, we were a little bit naive about the world. We thought that a lot of these issues had been fixed. That is a very naive stance to take, but we thought that women’s equality had been somewhat achieved, we thought that the horrible racial abuses of the past few centuries were on a trend toward getting better. I think what Trump exposed is not so much the lack of his own character but the gross naiveté of this feeling in our country that things were becoming more equal and that people were generally becoming a little bit more accepting of people who are different than them. I think the majority of the people in this country are becoming much more open-minded, and the evidence is that people who live in close proximity to people who are different than them are much more accepting of those people. And it’s people who live far away from people who are different from them who become fearful.

AC: I think white liberals were very, very surprised by Trump’s election. We were very, very shocked. We were shocked by the fact that it meant that white people were as racist as people of other races have known. There are neofascist movements happening all over the world and we’ve been looking at those things and saying, “It could never happen here.” We were just being very naive, I think. People in other countries know how easily it happens. Even very recently. As a culture, in every way, our American exceptionalism—even in people who aren’t flag-waving, America-first people—we have had this ingrained in us that we are better. Our country was founded on these principles that are so important to our country that we thought it couldn’t happen here. We’re just realizing all the time that these things are very tenuous. Our constitution, our beliefs in ourselves are not what we thought they were. But other people did know that.

MR: The thing that surprises me is that most was that forty percent of the country seems behind someone with this much toxicity.

AC: It’s not an accident that our education system has gone down so far. People don’t learn civics. They don’t understand how the government works. And it’s not “they.” It’s everyone. It’s all of us. The way that our grandparents or our grandparents or even we in the nineties were taught things, it’s getting eroded every year. There’s less and less money for education, there’s less money for teachers, it’s not seen as important. Then you end up with a populace who doesn’t even know what the different cabinet positions are supposed to do, so they don’t care and they believe the hype that they’re being fed all the time that the government is just there to take all their guns away.

MR: Since we’ve touched on kids and education, let’s bring the album back into the discussion and dig into the new family aspect. How does it feel to be moms now and how did that affect your creativity?

LC: Time management becomes a huge element. The way that you structure your day is just different when you have a small child in the house. That’s a huge thing, but the flip side of that is everything becomes much more meaningful everywhere in the world, and that can lead to creative expression and creative epiphanies and a deeper understanding of other artists’ work that you’ve taken for granted in the past. Everything starts having more meaning. You suddenly start listening to different kinds of music around the house to pep up a little kid. Every night, we sing lullabies; every nap time we sing lullabies. My daughter is constantly singing around the house. Abigail’s daughter is constantly singing and playing her little ukulele. Our dad is constantly singing for the kids and writing songs for them. Now we frequent our friends’ sing-alongs in New York City. We have a friend named Hopalong Andrew who’s an urban cowboy who does sing-alongs. It just shifts things a little bit. I think it deepens the creative process ultimately.

AC: It makes your creative time more valuable in some ways. You have less of it. With no structure to my days, it’s very hard to get anything done. So in a certain way, with the two-hour nap time in the middle of the day, that’s my time to do X and Y. I think for songwriting or just creativity in general, the more structure you can put on it sometimes helps because, for me at least, the enemy of creativity is a blank page, in every metaphorical way. The more ways you can hem it in with a task like, “I’m writing a song about this, I have this amount of time to do it, I have to have it done by then,” that has been helpful. Although, I will say when we were collecting songs for the EP and we were trying to go through multiple songs and whittle them down, that was a productive time for writing and finishing things. I’m a great starter of songs, and then, unless I have somebody saying, “You have to send me demos tomorrow,” they never get a third verse. It was good to do that and since then I have yet to finish that much.

MR: As a fan of your family forever, I imagine that you dad is fast at work coming up with a children’s album for your daughters, no?

AC: Since they were born, I think he’s put out three adult records and they’re two. He’s busier than ever. He’s super prolific and he loves keeping busy. He did write a song for each of them when they were born.

LC: And he did write two songs about being a grandfather right after they were born, so he’s having some introspective grandparent time. And he plays for them all the time. They love his records. He’s got two littlest, newest fans.

MR: {laughs] The Chapin Dynasty really is like none other, possibly with the exception of the Taylor-Simon gang. You have The Chapin Sisters, Harry, Tom, Jen… So why did you record an EP and not a full album this time around?

LC: Very good question! I think the reason is our good friend Evan Taylor, who has music directed The Everly Brothers project with us and he’s played drums live with us going back quite a few years now—we met when he was producing a Black Flag country record way back when—he is an incredibly talented guy and he wanted to start a record label. He said, “I’m going to fund this project and put you in the studio and this is how many songs.”

AC: He wanted to do an EP.

LC: This was his brainchild in terms of being the label, so we just gave him an EP because that’s what he wanted for this project. We could have certainly continued with it. We have other material that will eventually make it onto some other recording. It’s like a short story versus a novel, I guess. It’s kind of a fun thing to do an EP. It can be all of one piece. It can feel a little less serious, less daunting. “Oh, what are some songs we’re working on right now? What would be fun to do?” It had a little bit of that adventurous quality because of the format. When you do an album it’s like an “album” with a capital “A.”

MR: What charmed you into doing a Hilary Hawke song?

AC: It was kind of timing. She had just played it for us when we were working on the songs and we had loved it and performed it maybe one time—it all happened within a couple weeks. We were playing songs for Evan and he fell in love with it just as we had. She’s a really amazing banjo player, that’s kind of her main job in life. She plays on Broadway and she plays with a million bands. She’s a songwriter, obviously, and has a few projects, but in our band, she was playing upright bass since we met her at a concert a couple years ago, and she’s been playing upright bass with us for the past couple years. She was going to be in the studio with us anyway, and Evan knew her through us so he was charmed by the song and wanted to include it, and we did, too.

LC: She brought the song to us and said, “Hey, I wrote this for you girls too sing.” We thought that was the sweetest thing, and it was nice that we loved it. She had a vision for it to be sung in two part harmony and immediately, upon hearing it, we knew exactly what to do with it. It was in our wheelhouse. We thought it sounded like a classic and we loved it.

MR: Evan’s worked with other artists in addition to you two. Do you feel his adventures with other groups come into play when you are making records together?

LC: Evan Taylor brings a lot to the table musically. I think it all gets filtered through the various projects he does. It’s hard to know exactly what comes from where.

AC: He’s also very personally reserved and private. When Bernie Worrell was still alive, he had us play with the Bernie Worrell Orchestra, singing one of our songs. We have experienced that, and Jimmy Destri was also in the orchestra for that show, he was the other special guest. We definitely have seen that side of Evan. He was the music director of both of those projects as well, and they’re a huge funk band. On the surface, it’s very opposite of a soft folk duo, but I think that his musical influences are very vast and varied and I think they definitely do filter down.

MR: You’ve mingled with what you’ve learned from those experiences, then incorporate them consciously or unconsciously into what you’re doing? Like maybe when you recorded with She & Him?

LC: I think unconsciously, yes. Consciously, you can’t separate anything out; it’s all like a big soup.

AC: And also both Matt Ward and Zooey Deschanel, obviously, are extremely talented performers and musicians, so spending that time with them, watching them, learning from them, I think they definitely have influenced us in many ways. They also were very good at really crafting a show. That’s something that I think about sometimes. Zooey had really specific ideas about the set list and how it had to go, like in what order, which song had to go at what point, because of the arc of the audience’s emotions. Sometimes I think about that when I’m writing our set list.

MR: How do you feel that you’ve evolved from your Toxic album to now?

AC: When we started with Toxic, it was definitely on a whim. We definitely didn’t think that we were a band. It was just everybody’s side project. It was done in a very ironic way. It was supposed to be a joke, kind of. As we recorded those songs, and especially that one [“Toxic”], it wasn’t a joke, and we realized that it touched a lot of people and it got a lot of airplay and we realized that singing together with our sister Jessica at the time was something that really was important to us. At that point, we didn’t really write songs, so that was really the beginning of our trajectory. From there, we’ve definitely gone through a lot. We learned to write songs, learned to play guitar… We grew up in a musical family but we weren’t trying to be musicians. We didn’t want to perform, really. That was the family business that we were running away from.

LC: We sang in harmony all the time when we were kids, and with Jessica our other sister whenever we were together, but it was never something we took seriously; it was just sort of a silly thing. It was kind of a way that our parents got us to stop arguing when we were kids. They’d be like, “Let’s sing together!” It was something that we always got so much joy out of but it was a very casual thing. I don’t think we really realized that it was different from what other people did until we started arranging these songs. I don’t want to say it was a secret thing we’d always done, but once we put it out there, it was like, “Oh, this is fun but people will actually support this as something that we do?” It was a bit of a surprise. It was something that you do in the privacy of your own little world and then suddenly, it’s validated by people outside of you. It was like a door opening and sunlight pouring in over all this possibility. I think that was really what happened. We all kind of thought, “Well, this is fun,” and then we didn’t really know where we were going with it, but we didn’t want to stop.

MR: That sun pouring in was probably California sun thanks to KCRW that takes credit for launching The Chapin Sisters!

LC: [laughs] Exactly. It was probably literally sunny that day. And it was an adventure, really, to be doing that. Jessica, our other sister was a bit older than us, we were just out of college, and she was living in LA. So was our brother and he was part of the motivating force for doing those recordings. He had heard us all sing together at my college graduation. We all just jumped up on stage. At my college, they had my dad do a little set because they would tap people’s parents to do fun things at the graduation. We jumped up and the three of us sang a song together and our brother was like, “Whoa. When did you start doing that?” He kind of hadn’t realized we were doing stuff like that. You know, it kind of happened that we had some support around us and that was really important to us. I don’t think that any of us had the confidence at that time to veer off track from what we were doing to do something like that, but it worked. The stars aligned and we were all going through life transitions and it worked that we were all in the same physical space to do it.

MR: Considering you’re Chapins, it seems like you were doomed to do it whether you like it or not. Can we talk about your family for just a second? Let’s go to WHY. You’re all still pretty heavily involved in World Hunger Year, a foundation started by your uncle Harry decades ago. What is the foundation doing these days? How has it changed or evolved and how are you both contributing to it these days?

LC: The organization has grown so much and the work that it’s doing is really amazing and it deserves to have a spotlight on it any way it can. I think its mission has broadened from the specific focus on hunger to the broader concept of “food justice.” You don’t want to just give people any old thing to eat. People need healthy food and they need to build self-reliance. There are food deserts all over our cities and all over our country, rural areas as well where you can’t find food. You can only find highly-processed, packaged food. You don’t see grocery stores that have fresh vegetables and you don’t find necessarily affordable ways to feed your family in a healthy way. All of these things have come into play beyond just the traditional food bank, which is still a very important aspect, but it’s also getting lots of local organizations together and shining spotlights on people who are doing really amazing work all over the country and the world for the food justice movement. It’s creating communities of change and self-reliant systems.

AC: And just connecting the people who need those resources with the resources. One of their most tangible day-to-day things is a hotline that hungry people can utilize. If somebody that you know is hungry and needs some help or some food, they connect you with the correct food bank in the area. On a very simple level, that’s one thing under the umbrella for all of those organizations in the country. We are not board members but we help them in every possible way that we can. They’re our organization of choice. We donate time and benefit concerts and proceeds from album sales to them. I would definitely like to be more involved in the future. Our band is a board member, Jen [Chapin] is a board member, our uncle James was a board member. The family is very, very involved.

LC: It’s a very large and very professional organization. They have incredible people working there day-in and day-out doing the hard work of running this organization and keeping it going. We want to shine a spotlight on those people. We’ve also been recently interested in another cause, which is the National Diaper Bank Network.

AC: It’s kind of a tangential association.

LC: Food stamps do not cover diapers. There’s no public assistance program for diapers, which is something that probably we should all know but we don’t really think about it. This is an issue that affects families because it’s just another reality of life. We’ve been kind of talking with them and trying to work with them as well. That’s another cause that really deserves attention right now.

AC: It’s again one of those things that people see as a women’s issue, so it doesn’t get the coverage or the concern—not from people at large but the from the government. The people who are running food stamps. The thing is that we all wore diapers. Men and women are both parents and men and women both care about being able to afford diapers for their children. And they’re very expensive! They really are. There’s also a very large hierarchy of diapers, and bad ones are noticeable. There’s also a hygiene issue and health issues that go along with not being able to afford to change a diaper as often as you should. At the moment, now that we’ve had our babies, we learned about the diaper bank association and we also just realized, “Wow, that is a considerable expense in our lives every month.”

MR: You’re creative artists, new mothers… How do you also find the time to be socially conscious? Is that a Chapin gene?

LC: We’re trying. [laughs] I don’t know if we’re succeeding at all of it. It’s what every mother does. Everybody is juggling. We are more privileged than many, many, many people on this planet.

MR: How do you keep your energy going through these toxic times?

LC: I would say coffee.

AC: [laughs] Yeah. Having a young child is a thing that also gives you energy in a way, especially for the social issues, because you just realize how unfair so many things are and how luck-driven everything is. Poverty and all of that stuff is completely imbalanced. For me, becoming a mother gave me so much more empathy. I feel like I was a pretty empathetic person, but now imagining trying to do everything… Like Lily said, we’re extremely privileged, we’re working mothers, but we also get to spend time with our children which is a luxury that many, many people in the world don’t have. We’re able to take our kids with us when we do a lot of work and we’re very flexible because we’re self-employed and we get to spend time with our babies. So many mothers around the world just don’t have that luxury.

LC: Or we should say they don’t have that choice. There are some men who equally would want to be with their kids. The luxury is the choice.

AC: I don’t mean it like, “You should be a stay-at-home mom.” I just mean some people don’t get to spend any time with their children.

MR: And what advice do you have for new or emerging artists?

LC: I think it’s a good time to be an emerging artist because you can just make music and put it out.

AC: But that being said, it’s very hard to find visibility. I think the most important thing is to just keep your eye on the joy of doing it. That’s the most important thing. If it’s not fun, what’s the point?

LC: Play and try to listen to people who are better than you, and play with people who are better than you. Don’t shy away from seeking out the people in your community that are already really deep in this stuff because they’re everywhere and there are people around that have a lot to pass on.

MR: Right, and intimidation tends to be a factor for many creative people. I think as a creative person, it’s natural to protect your heart.

LC: Exactly.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne