September 7, 2014

Motorcycles, Riptides & More: Chats with Loudon Wainwright, Vancy Joy, John Velghe and Rocco DeLuca

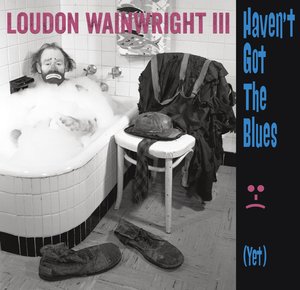

A Conversation with Loudon Wainwright III

Mike Ragogna: You've got a new album, Haven't Got The Blues Yet and it looks like you're kind of expanding your style here. What prompted that?

Loudon Wainwright: The producer on the new record, Haven't Got The Blues is this fellow called David Mansfield, who's highly regarded and pretty well-known as an all-arounder, a guy who plays a lot of the instruments that have strings on them, I believe; fiddles and guitars and pedal steel guitar and mandolin. He's also a friend of mine and has been on a lot of my records over the years. The way the record came about is that he has a little studio in Maplewood, New Jersey, and I used to go out there and he had some skills on the board, being an engineer. We just put this together over the period of about a year. I don't think we were thinking conceptually of what was going to make this one particularly different; Older Than My Old Man Now focused a lot on death and decay of course and the new one is death and decay and depression!

MR: Well, there's your expansion.

LW: I'm heading in a new direction: Down!

MR: [laughs] Yeah, yeah. Okay, how did the songs come about for this one?

LW: Some of them are new. "Lookin At The Calendar" is new. Some of them are old. "In A Hurry" was written maybe even ten years ago. Some of these songs need homes. What I've been doing on some of the last records is taking a bunch of songs and trying to create a fifteen minute sonic experience and explore a couple of themes along the way.

MR: Where do you get your inspiration as a writer?

LW: It's hard to be objective about oneself. I don't know what's different, it doesn't feel like anything has changed in the 40 years that I've been writing songs. Basically, what happens is I get an idea or something pisses me off or amuses me or upsets me, certainly, something happens to people who I love or people who I love do something to me and then I find myself grabbing a piece of paper and writing some words down and putting a guitar in my lap and trying to fashion a little tune for it. That's pretty much how it's always been. I guess my sensibilities have changed or coarsened over the years, I don't know, but it all feels pretty much like it was just yesterday.

MR: Which brings us to your new soon-to-be holiday classic, "I'll Be Killing You This Christmas."

LW: Yeah. That's a song I wrote about a year ago. I wrote it after the Newtown, Connecticut shooting. Occasionally, I get into social commentary. I'm old enough to remember when there was such thing as a protest song. I used to go to the Newport Folk Festival and hear Pete Seeger sing them. After that horrible shooting I was sitting around my house with the Christmas tree having just been erected and I made a little joke to myself, "I'll be killing you this Christmas," thinking that the song was going to become about a guy wanting to kill his wife or his girlfriend or something. Then all of a sudden, this gun thing swerved into the picture and it became a little more serious than that. It's an interesting song, but it's a tricky one. You have to be careful where you sing it but I'm happy that it came out.

MR: "God & Nature" has an interesting perspective take as well.

LW: Yeah. My mom, who was southern Baptist from Georgia always wanted me to be a preacher. Instead I decided I wanted to be an actor and a performer, but that song is like Episcopalian gospel music or something. It was a funny song that just kind of came out, I'm not even sure why. I do know that I was watching some of the debates in the lead-up to the 2012 presidential election, as I recall I was somewhat inspired by some of that stuff.

MR: What are you looking at in the news these days?

LW: Well now it's a question of what's making me look away, actually. When you see four kids on a beach that just got blown away... The news has always been pretty bad, but it just seems particularly dreadful in so many different places, but in the Middle East in particular. It's tough to watch the news or read the newspaper or to dwell on it. In terms of writing songs about it, I don't know where I would begin to write about any of that stuff.

MR: It seems like politics nowadays is all about "I'm not going to let your side win." They went after Bill Clinton and now Barack Obama viciously. Do you think this has been happening for a long time or did things get worse when Obama got in? That's sort of the elephant in the room.

LW: Well, it's hard not to think that some people didn't just make up their minds to say "no" about everything. I know that there are theories and even evidence about that. Politics at that level, it's a mystery to me how it's done. I don't know why anybody would even want to do it.

MR: Do you think there's any way out of the extremely toxic legislative environment?

LW: Unfortunately, I'm enough of a pessimist to think that things are probably going to get worse. I don't know, you'd like to think that there isn't a really viable republican out there, but who knows?

MR: Now, you also have this show, The Posthumous Collaboration. What is that?

LW: When I made Older Than My Old Man Now, one of the parts of that record was that I included a couple of selections of my father's writing, I recited them on the record and then connected them to a couple of my father's songs. My dad was quite a well-known journalist in the sixties and seventies and eighties, he wrote for Life magazine, he had a column called "The View From Here." When those columns first came out, I didn't really read a lot of them because of the father-son whatever. But I went back a few years ago after I made my record and I read all his work. Then I got this idea that I could, as you say or as I said, have a kind of posthumous collaboration, combining and connecting some of my songs with my dad's writing. He died in 1988. It's been great, we originally did it down in North Carolina last September, in Chapel Hill, and then we just finished four Monday nights in New York at a theater in Midtown. I'm looking around for a more permanent home for the piece, it's about an eighty minute piece of about thirteen songs and a lot of my dad's writing. I'm having a blast doing it and people seem to like it also.

MR: Is it an evolving show? There's got to be a degree of improv in there, no?

LW: Parts of it are nailed down. I'm trying to find the right combinations and get a flow to it. I've been performing for long enough to know there has to be an arc to the evening, the eighty minutes, but it's still in development, so to speak. I think I'm close to having it pretty much finished and again, hopefully, I'm going to get to perform it in some town somewhere for a certain amount of time.

MR: You said you wanted to be an actor at one point. When did your focus shift more toward music?

LW: Well, in the late sixties I went to Carnegie Mellon, which used to be called Carnegie Tech, which is a fine acting school in Pittsburg. But then I dropped out and became a hippie and did that for a while and then wrote a song. So that's how I swerved over to music in about 1968. But occasionally, I dabble in the dark arts of thespianism. But I earn my bread and butter mostly as a singer-songwriter.

MR: I so remember your appearance on M.A.S.H. as Captain Spalding.

LW: The singing surgeon!

MR: And there's your appearance as an obstetrician in the movie Knocked Up.

LW: Oh yeah. It was great to get Katherine Heigl up there in the stirrups. I need to thank, my old pal Judd Apatow, who's been great. He gave me and Joe Henry that job to write the music, he's given me parts in a couple of his projects, acting roles. He's expressed an interest in this theatrical thing I'm doing, Surviving Twin. Judd is my patron, I love Judd.

MR: [laughs] Speaking of the hippie generation, you wrote "Dead Skunk In The Middle Of The Road," one of your trademark songs and an anthem of the era.

LW: I thought you were going to talk about "The Acid Song."

MR: [laughs] Right on! Let's get there, too!

LW: If we want to talk hippie, let's talk "The Acid Song." But yes, "Dead Skunk." We talked about the elephant in the room, now let's talk about the dead skunk! Speaking of Bill Clinton, it was number one in Little Rock, Arkansas, for six consecutive weeks in 1973.

MR: [laughs] Was that because of Bill Clinton?

LW: I somehow imagine that he and Hillary were making out in the back of a rambler station wagon and that song was on the AM radio while he was you-know-what-ing.

MR: I'm pretty sure I read that in her book Hard Choices.

LW: Yes! Hopefully. But the "skunk" thing sure paid for a lot of child support, let's put it that way.

MR: I guess we ought to weasel on over to that topic.

LW: Let's do the family thing!

MR: Yeah. You've been associated with the McGarrigle and Roche musical dynasties. You're father to Rufus Wainwright--who, at this point, is almost as iconic as his dad--plus two more amazing talents, Martha and Lucy...

LW: Well, Rufus and his sister Martha, who's also in show business, are my kids from my marriage to Kate McGarrigle. Kate and I split up when Rufus was three and Martha was just a few months old. In terms of the nurturing, I'd say I was a part-time nurturer and Kate did the lioness' share of the nurturing, and she was quite a lioness. Rufus and Martha and my daughter Lucy Wainwright Roche, daughter of another fabulous artist, Suzzy Roche, those kids have been around show business forever. Then I have this twenty-one year old daughter who can play the guitar, so look out.

MR: Seems like there are some pretty awesome genetics at work here.

LW: I suppose since the moms were artists, the deck might have been genetically stacked, so to speak.

MR: What's your view of the "singer-songwriter" genre these days?

LW: You've got me. My focus is mostly subjective. I've been trying to do my job, which is come up with the next song. In terms of what's happening to the scene or folk or Americana or whatever you want to call it--guys and gals who play guitars--it's the same five chords everybody's playing. They're singing about themselves and what's happening in the world. In that regard, it hasn't changed much. I suppose some of the haircuts have changed, but then they come back around to what they used to be. I don't know what I can say. I try not to even listen to other singer-songwriters. That is my idea of a bad time. Trapped on an island listening to the new John Prine or Steve Forbert album would be torture. I think those guys are great, but I prefer dead black jazz piano players like Thelonius Monk if I'm on my desert island.

MR: Not even Steve Forbert songs? Sorry, that was my shameless plug for Steve Forbert.

LW: I love Steve Forbert, and that's why I don't want to listen to his songs. I love him too much, I don't want to hate him.

MR: Loudon, what advice do you have for new artists?

LW: Play the guitar every day for fifteen minutes. I really don't know, I can't offer any advice, I can just only say, "Good luck and get a real job."

MR: [laughs] Is that what you would have told Loudon Wainwright III?

LW: No, I'm being disingenuous. I think it's great to not have a real job. I'm a guy who's not had a real job for almost fifty years. I think that's the goal in life; to somehow make a living without having to really have a job.

MR: One last thing. "Man And Dog," what's the story behind that one?

LW: Ah, yes. I live up there in the upper west side of New York and Harry, our dog has to be walked, as do I. We go out there and fool around in the dark--it's not what you think, of course. People love that song. In fact, we're going to make a video of that song next week. I expect it'll be going viral soon. There you go, I'm going to have another funny animal song that's going to be a hit. The bookends of my career!

MR: And let's talk about your Grammy win, sir. You got Best Traditional Folk Album for High, Wide & Handsome.

LW: Yeah, how about that? I have to thank the guy who had the idea and also produced and paid for the record, a wonderful guy called Dick Connette. He also produced Older Than My Old Man Now. I told Dick that I loved Charlie Poole's records from back in the twenties and Dick said, "Well let's do the Charlie Poole Project." It's thirty-five tracks--two CDs, a seventy four-page booklet--and we won the Grammy. So thanks so much to Dick Connette for that. Not to mention Charlie Poole, of course.

MR: What's in the future beyond Surviving Twin?

LW: I'm not looking beyond that. I'm hoping we can do that somewhere and then I'm out there hoping and wishing and fishing for the next song, because that's my real job. It's not real work, of course, but I've got to write the next song. That's how you keep going in this line of work.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

KATHY SLEDGE'S TRIBUTE TO BILLIE HOLIDAY

According to Kathy Sledge on The Brighter Side Of Day...

"I have been performing my tribute to Billie since I was 16 years old in the early Vegas days with my sisters. I have been told I practically bring Billie to 'life' on stage. So I felt, 'If this is the case, then what would it be like if we could step back in time? There's Billie, Louie Jordan and the Timpani 5, Bud Powell, Max Roach... Let's take the audience to this place.' And so we do just that!

"In the First Act, we propel you in to the forties through the music. In the Second Act, we bring Billie Holiday to life. It's very passionate to lift up the legend and the legacy! I felt like the need to focus on the depths of the music as opposed to the depths of the addiction. There is so much more to her story when it comes to the music. I am finding there are so many others embracing this concept and appreciating it as much as I am.

"The response has been overwhelming! The show has been sold out everywhere we go...'we,' the musicians, Somebody Tell Joe, The Chop Horns and myself."

Chris Surrey, Partner & Director of Creative Lab @ PaintBox Labs Media Group in Seattle

A Conversation with Vance Joy

Mike Ragogna: So what's with all this about Dream Your Life Away stuff?

Vance Joy: That's the title I came up with, just because it describes my experience of starting to write songs. Going down that path is a bit unorthodox; most people start and say, "Oh, you know what, I can't do that." I'd been doing University and other things but I'd written a couple songs because it was a dream I had been keeping secret; doing music. About a year and a half ago I decided to take the plunge and pursue that dream and I'm really glad that I did because I'm on this path at the moment that's really exciting and surreal.

MR: I hope that having a number one record on alternative radio was part of your dream because it came true, buddy!

VJ: It was just all about writing something I was proud of and felt was pretty decent, but it's a nice thing to accomplish. I know I've got a lot of people who worked hard to get the song out there.

MR: And congratulations, good for you. So let's talk about "Riptide" and what went into it.

VJ: I started writing that song in 2008, I didn't think too much of the first two lines, it was a simple song, you know? I thought, "I don't know if this is going anywhere" so I kind of shelved it. At that time songwriting wasn't really in my plans at all, it was just something I did as a hobby. I still do it, it's just like a hobby I happen to do all the time. But I left it alone for four years and then I came back to it when I started playing ukulele and I played this melody that ended up being the melody for the chorus. Those two lines from 2008 resurfaced and I built them up and in a couple of days I had the song done. It came out quite effortlessly, the lyrics were kind of stream-of-consciousness. It took a bit of fitting pieces together but there were a couple of breakthrough moments where it came together really nicely, the song stuck together really strongly. I went and played it to my friends and family and I got a really good reaction. I've been playing it since the end of 2012 and it's kind of taken on a life of its own.

MR: Awesome. You hit number one with a song that you started writing in 2008. You should test the waters with a song you started writing in 2007.

VJ: [laughs] Well, there was a song I started writing in 2006 called "Georgia," it's on the album. It was a guitar riff that I couldn't find a place for, but then on New Year's Day this year I finally found a melody that went over it and sounded good. It didn't take long for the song to come together after that--it was just that breakthrough thing that happened five or six years after the original moment.

MR: No wine is fine before its time?

VJ: [laughs] Yeah, it's a long time between drinks.

MR: You're penetrating the US market with this new album. Have you found it particularly challenging to break into our market? What would success in the US look like to you?

VJ: I've always been prepared for a long slog in America. I knew there were a lot of radio stations, a lot of territory to cover, a lot of people to convert, I guess, But I always had good experiences playing in America from the start. There were a few people who would come and see me supporting someone and then they'd come to see me. There's always a lot of hope, I think, even if it's on a small-scale it's always encouraging. I've always been pretty optimistic about being able to get a group in America and make it viable to tour there. In terms of what I envision about America, I feel that there are examples of really good artists who are consistent, like John Butler Trio who tour around America based on a loyal fan base and his consistent songwriting and the fact that he's a hardworking musician who does a lot of touring. It seems to me that if you're willing to do all those things you can have a home in America as well, and having a home in America is something that adds a lot of longevity to your career.

MR: You must have had some clue this could happen, especially when "God Loves You When You're Dancing" was big.

VJ: I'm pretty lucky. I've got a couple of good managers and they always saw it as a possibility, they instilled in me the fact that I would need to commit a lot of time to doing it, so I've spent the last eighteen months slogging it out, being on the road most of the time and facing all of the challenges of doing an album in that space. I think it's totally worth it now that we're finally coming to the surface a bit and people know my music. I've been playing in a lot of festivals, that's been amazing.

MR: "Winds Of Change" is another highlight. That came together in 2009 and you feel that was one of your strongest moments in songwriting, right?

VJ: Yeah, that was a strong moment because it was the first song I wrote that was coherently decent. I wrote that song and pretty secretly in my heart I was totally switched on to the possibility of trying to write more songs and wanting to do music and be a musician. It was a turning point, writing that song. That's why I thought it was a good emotional start to the album.

MR: Apparently, Hemingway was inspiration for your song "First Time"?

VJ: Yeah, there's a line in A Moveable Feast where he talks about listening to a story from one of his colleagues and it really hits Hemingway's heartstrings, but every time he hears it after that first telling it doesn't seem to have that same impact even though the story gets better and more detailed and the storyteller gets better at telling it, it never has the same punch. I kind of like that idea. I wanted to write a song that had that idea in terms of relationships.

MR: "Red Eye" references a modern classic movie, Scent Of A Woman.

VJ: There's a great line in that film where he's having a rant, which is not unusual for Al Pacino, especially in that movie. He has a big speech and he says, "Even a dog gets a warm bit of sidewalk to lie down on" or something along those lines. I really love that idea of the dog sunning itself on the sidewalk so I just stole that and tumbled it around a bit and put it in the song.

MR: The recording process for this album was pretty unusual. Part of it was finished in a tree house?

VJ: Yeah, the producer Ryan had this crew who were doing a show and he said, "Build a tree house for the people they're doing a show about." They built a tree house on his beautiful farm property with some old Douglas Firs in the surrounding area. They built this tree house in a couple of weeks, it's a beautiful little studio that's great for vocals and putting finishing touches on songs. We sat up there for a couple of days, it was really intimate, doing backing vocals, hashing out ideas. That was one of the really good moments in the album because we'd done much of the songs and we were just listening back and finessing a few little things.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

VJ: I think the best advice is just to worry about your songwriting. If you really want to be doing music that should probably be your first concern; making good songs. Don't worry about your style or sounding like someone else, don't worry about getting the right kind of press release for your gig and getting all of that stuff. That stuff is all important, but it's better in the hands of people who work in the industry. Just worry about writing good songs and recording them to the best of your ability.

MR: "Riptide" has had fifteen million views on YouTube, and it's not silver, it's not gold, it's platinum in all these countries all around the world. What kind of impression does that leave you with something you created?

VJ: It's kind of surreal. Last year it started making an impression on the internet and getting a lot of listens and stuff and that was when it blew up for me. I was like, "Wow, this is going to happen, people actually want to hear this song. This is good for my possibilities of doing what I want to do." Since then it's kind of kept getting bigger and bigger and I'm almost detached from it. It's really become its own thing. It's strange to think that I actually wrote those lyrics, I actually wrote that song, it actually came out of me at one point, it wasn't this big thing, it was just this little tiny song that I had written. It didn't have that aura of being a big song.

MR: What do you think it was about that song that resonated and made it that big?

VJ: I think the recording is really special. We did it in a day. My drummer and I went to a studio in Melbourne and spent seven hundred dollars recording it. It was my first proper experience in a proper studio, so there were certain naiveties that went into it and I think that comes through. We didn't play to a click track so it comes flowing in and out of time. The choruses are almost a little bit off, I think there's something really human in that, it's almost like a bizarre, strange chemistry which can work sometimes. I just did a couple of vocal takes, really raw at the end of the day and just pushed super hard. It felt like the way that I've learned to sing was probably more controlled but there's a certain looseness and lack of control which I think works for the song--besides the fact that it's a catchy song and there are really colorful lyrics. I think all that stuff comes together and makes a really tasty song.

MR: Is that also good advice for a new artist?

VJ: I think so. Recording a song in a day, or at least allowing something magical to happen by throwing caution to the wind is something that I'm a believer in.

MR: What's the best advice ever given to you?

VJ: I had a couple of good ones. A singer-songwriter from Australia said, "Just write what you write," which I really like. You get involved in songwriting and you're at the mercy of whatever. Songs come into your creative channels, so just follow that intuition. I also got another advice about songwriting which is that it's not going to be easy but every little thing that gets in the way and makes a song hard to write or makes you think that you're not at the top of your songwriting game is just an obstacle you can push through. It can be overcome. That always gives me hope. When the songs aren't coming I just think of the fact that I'm just standing in front of an obstacle that I can get around.

MR: What's the future look like for Vance Joy?

VJ: I think in the next couple of years I'll be playing a lot of shows. I want to be writing songs and record again some time, when there's a bit of time off. I don't look too far ahead, I've got vague plans but my whole mantra is, "One foot in front of the other."

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with John Velghe

Mike Ragogna: So there's something called Motor Bike Tour--The New Hearts MC Road Show occurring. In order to ask you a question, I have to understand what the heck is going on here. John, what the heck is going on here?

John Velghe: The New Hearts Motorcycle Club (MC) is a charitable organization I started this year to benefit organ donation and transplant recipients. The goal of this inaugural tour, or Road Show, is to raise awareness of organ donation, and to try to raise funds for Transplant Patients and their families. The idea came from the album, to take the concept of motorcyclists being called "organ donors" and turn that on its head. To do something throughout he bike, through music, that benefits organ donation and organ transplantation.

MR: How far back do you and motorcycles go?

JV: I go back with motorbikes almost as far back as I go with music. When I was little, my uncle--a drummer who helped my parents pick out my first drum set--used to take my cousins and I for rides on his motorcycle through the hills of Western Wyandotte County Kansas. Then when I got a little older, I used to ride one of my neighbor's dirt bikes around this school yard behind our houses during the summer. A few years ago, I bought a Monza Blue 1976 BMW R60/6. It had been in a garage for 15 years. The garage was located on the same street where my grandma grew up the East Bottoms of KC. Since then I've done a complete mechanical restoration of that bike, I call her Lola. I've had it completely apart and rebuilt it from the crankshaft out, front end to rear. It's my daily rider. I have a newer touring bike I'm taking on this tour.

MR: Is anyone in the band an actual organ donor? Just curious.

JV: Not that I'm aware of.

MR: How did the gang creatively come up with the material for Organ Donor Blues? What was the recording process like and in what ways does this album differ from your last one?

JV: I'd been writing the bones of most of these songs since the last record came out. Lyrics, chords, melodies, etc. were in the works and I'd been bringing them into rehearsal steadily since then. So we've all lived with these songs for a couple years or more. In that way, we've all been able to really dig into our parts and refine what we wanted to do before we ever recorded them. Where it really differs from the last album is in how we recorded it. The last album was done in parts here and there over months. When it came time to cut the basic tracks for Organ Donor Blues, the four of us--Mike, Matt, Chris and I--all got in the studio with Duane and just played the songs over and over until we had parts we liked. We tracked 14 songs in a day and most of the basic tracks you hear are the ones we cut in the studio. We came back and did overdubs for things like horns, pedal steel and vocals, mostly due to space constraints. Even in the nice big room at Weights and Measures, we didn't have enough space for all eight of us to do our thing without stepping all over each other. But I think the end result was what we wanted; a live-sounding record. The sound of a bar band hooting and hollering and twanging together.

MR: Considering the amount of work he contributed to the album, was it due to it being impossible to remove guest artist Alejandro Escovedo from the studio, was it a kidnapping on the band's part, a debt now repaid or something nefarious that explains his appearance on every inch of Organ Donor Blues? When you finally got him out of the studio, did he return pretending to forget something and stay another few days?

JV: Ha! I was on the phone with Alejandro a few days before we cut the basic tracks and he asked what I was doing. I told him getting ready to go make a new record and he said, "So what am I doing on it?" I said, "Whatever you want. Guitar, vocals, whatever." So come January, he travelled from a much warmer Austin to a bitter KC and took me up on my offer of "whatever you want." He spent about three days up here and kept telling, "You got me here, use me." I told him, "If you're gonna quote Bill Withers at me, I'm gonna take you serious." There are two other songs he played on that didn't make it onto this album.

MR: Was there anything during the experience of creating the album that anyone could have potentially needed or become an organ donor?

JV: Two weeks before we were supposed to record my left hand was smashed in a revolving door. A big gust of wind blew the panels and one 300-pound panel collapsed onto the other with my hand in between. It smashed my ring and the fire department had to cut off the ring. After 45 minutes of waiting on them, I couldn't grab the steering wheel on my way home. After I made sure I could hold a guitar neck, I went to the hospital and the doctor told me how lucky I was. He saw the ring and said if I'd not been wearing the ring I'd have lost at least one finger on my left hand. So, while not an organ, I might have donated a finger that day. And while I'm not a guitar virtuoso, that's the equivalent of a kidney to me.

MR: Which song on the album do you think best represents the talents of the band?

JV: I'd say "Beaten by Pretenders" or "On the Interstate." On those songs, you hear everyone brining their combination of talent, caring, and Midwestern work ethic to the cause. The vocal harmonies, Mike's guitar work, Matt's groove, Chris's sense of counter melody, and then those brawny horn lines and pedal steel. Those are the songs that make me remember what a beautiful and thoughtful band I have.

MR: And then there's that New Hearts MC Road Show. Despite this interview, that's still happening, right?

JV: It is. I leave in a few days. It's really going to be a great tour. Over 3000 miles with a guitar on a motorcycle. I'll get to see the country from a bike and friends in New York, Nashville and Durham along the way. If I can't tour with my full band, this is the next-best way to do it.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

JV: Take time every day to be centered and work on your craft. Write about everything. Feel everything. Find your own unique way to see the life you have. Do this for something outside yourself, expect the rewards to come from inside yourself, and make sure you reward everyone you work with as much as you can. People can feel unrequited, so make sure they know you love what they do for your songs. Always wear your ring when you go through a revolving door.

MR: Since Cher was part of a motorcycle movie--Mask--do you think she might like Organ Donor Blues?

JV: Sam Elliott was my favorite character in that movie, and I KNOW he'd like Organ Donor Blues. My friend was in a band called Cher UK and he likes Organ Donor Blues. So when you put those two together, it's pretty easy to see that Cher couldn't help but love Organ Donor Blues.

photo credit: Troy Critchlow

A Conversation with Rocco DeLuca

Mike Ragogna: Rocco, Daniel Lanois produces your project, a new self-titled album, though you've worked with him on your material before. How did you guys initially meet?

Rocco DeLuca: We met in Toronto once, then he came to my show with an eight ball and two hookers. I knew we would be friends for life.

MR: How does this album differ sonically and creatively from your previous releases?

RD: Sonics are high because Daniel is second to none when it comes to audio. He continues to push those boundaries with every project.

MR: What inspired or are a couple of stories behind these songs?

RD: These are inspired from letters that I would write to loved ones--some never were sent--I would come up with melodies while riding through the mountains and backroads of the country.

MR: You've worked with various artists including Slash. How have your collaborations influenced how you approach recording? How have you grown both in front of and in back of the board in the studio?

RD: I learn from everyone. Everyone has a particular line on something. I have little analog board in my little room and try to improve on things. Watching Lanois perform mixes in front if me has changed everything. I can't do it, but I know what it could be.

MR: Have you ever had any significant guidance as to your song crafting, recording techniques or musical career overall?

RD: Not really. I just read, and observe the things that turn me on like Big Bill Broonzy record on full throttle showing us what's what

MR: What is the story behind I Trust You Tov Kill Me, the album and the documentary?

RD: Never a dull moment with some good friends. They brought me along for the ride. I can't wait to get back to Reykjavik!

MR: What was it like working with Kiefer Sutherland on your video for "Save Youself," a track from Mercy?

RD: Kiefer and I just laugh at each other. He's so good at what he does. I have a lot love for him, his heart is bigger than Texas and I look forward to another project together.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

RD: I would hope that a new artist wouldn't try to please or be liked by anybody. I would hope that they did a thing for its own sake. An ambitious musician is one of the scariest things I have ever seen.

MR: What are you working on beyond the promoting the new album and what does the somewhat near future bring for you musically and personally?

RD: I want to live out my blues dream, wood shedding, sleeping under the stars, crystal clear pure tone and slide guitars moaning until I cry, and helping my friends, including Davey Cooperwasser and Jonathan Wright who are this tour with me.