March 31, 2014

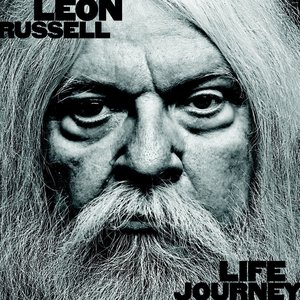

Life Journeys: Conversations With Leon Russell, Judy Collins and John Gorka

A Conversation with Leon Russell

Mike Ragogna: Hey Leon, Life Journey, your latest album, was recorded with Tommy LiPuma, Al Schmitt, Elton John...you have an awful lot of friends rooting for you. Do you feel the love?

LR: Well yeah, it was nice. Elton was primarily responsible, he wanted me to do an album of my own. So yeah, it was great, I had a lot of help.

MR: Life Journey...how did it come about and how did it get so lush?

LR: Well you've given me the benefit of the doubt that I know what I'm doing, but that's not exactly the case. Tommy and I had a lot of conversations before we made the record and I just happened to mention one day that when I was always playing my piano part, I was always imagining an ensemble when I played that sounded like Count Basie and had lines in between and so forth. So he showed up with one of Count Basie's writers and bass players and we went from there. The idea is a life journey occurred somewhat in the middle of the recording.

MR: The concept is sort of like a statement on what made you and where you are now in your life and music, right?

LR: There's kind of an explanation of it in the liner notes. They basically say there's some things that I've done in my life and some things that I've always wanted to do, so that's what it is.

MR: Some of these songs sound like they were made for Leon Russell, for instance, "Georgia On My Mind." What an easy fit this material is. When you listened back to these songs did you feel like, "Hey, maybe I should've recorded these earlier on?"

LR: I definitely wouldn't have recorded while Ray Charles was alive. He had the definitive version of "Georgia," but I was doing that on my show, actually, unlike many of the others which I did for the first time when I was making the demos for the writer to write the arrangments.

MR: And then you have what could be a slight nod to one of your own hits, "The Masquerade," with "The Masquerade Is Over," no?

LR: Well, not really. I used to go to jazz jam sessions in Tulsa that started at one or two o'clock in the morning and went to two or three in the afternoon the next day while we were jazz players that played Leon McAuliffe's hillbilly band were out there playing at those jam sessions. That's where I learned "The Masquerade Is over." I'll tell you what it is, I'd never sung that song. I'd played it for a bunch of different singers, but I never sang it until I made the demos for this record. I don't think that one has anything to do with the other, it's just a consequence of having this thing learned.

MR: At this point in your life you're turning seventy two soon, there's got to be some relfection on a lot of your sign posts and mile markers. How do you feel about your career and what you've contributed to music? What are your thoughts?

LR: I'm happy to have a job. What can I say? Sometimes one misses the sign posts as you're going down the road. They aren't as obvious as they become when you get to the end of the road, so to speak.

MR: Do you ever think about the days when you were doing the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour--you know, out on the road with Joe Cocker and Rita Coolidge?

LR: Yeah, I think about that occasionally, that was quite an event and I enjoyed doing it a lot, but the first rock 'n' roll shows that I saw were big variety shows with twenty and twenty five-piece bands and fifteen or twenty acts who would come out and do one or two songs each. I've seen shows that had Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino so that was exciting times for me. I was just trying to capture that a little bit. At modern rock 'n' roll shows you'd never see that.

MR: And that's why you touched on something a lot of people appreciated, it's an iconic album of the era.

LR: I guess so...I don't know, it got kind of mixed reviews when we did it. But isn't that always the case?

MR: Yeah, and I think over the years, it's stood the test of time. For anybody who's an afficionado of classic rock, that's a classic album.

LR: We had the movie to go off of, that helped a bit.

MR: I've interviewed Rita Coolidge over the years and every time, your name comes up with such a fondness for both those days and you. And you did write "Delta Lady" about Rita.

LR: Yeah, I wrote that for her, and also the song "Superstar," I didn't write that for her, but I wrote it because of her. She was the first person I ever heard use that word. She was talking about Dionne Warwick recording an album in Memphis down there were she lived and she said it was such a great pleasure to see a "superstar." That was the first time I ever heard that word, and I was kind of fascinated by it. It wasn't in common usage at the time.

MR: Yeah. If there was a hip moment in the Carpenters' career, you supplied it with "Superstar." You helped mold history a little bit there too.

LR: Well Karen Carpenter was just a singularly amazing singer. There was just not anybody like her. I produced a gospel duet called the O'Neal Twins; they were a couple of twin brothers who were soul singers and they sang gospel songs like The Everly Brothers. I asked them one day who their favorite singer was and they both said together, "Karen Carpenter." So that's kind of amazing for me.

MR: And George Benson had a big hit with your song "This Masquerade," which a lot of people have since recorded.

LR: Actually, Tommy produced that record, too, so I'm quite thankful for him. There was a period in my life where I was trying to write standards. I wasn't trying to write hit records. Standards are different, slightly, from hit records. The guy that plays the baritone saxophone in Tower Of Power [Stephen Kupka] came up to me one day and he said, "Leon, I've written twelve Top Ten records with Tower Of Power and nobody's ever cut them. How did you get all of those people to print your songs?" and I said, "Well I'm not sure I could explain it to you, since they're different songs, but a standard is not necessarily a Top Ten record at the start of its life. It just depends on if a hundred people cut it in ten years. Then it's a standard."

MR: Some of these things have turned into standards, "Day After Day," and "This Diamond Ring" among others.

LR: I'm not sure that was a standard.

MR: [laughs] As part of The Wrecking Crew, you could've just settled as being a piano player and had an amazing career, but you went solo and had your Shelter Records plus musical workouts with Marc Benno. What made you turn the corner or were you always trying to do that and you finally lucked out?

LR: Well I wasn't much of a singer, I mostly played piano for real singers when I played in night clubs and piano bars and stuff like that, but I started singing a little bit, I got a call from Denny Cordell, who was cutting Joe Cocker, and he said he had a deal where he just listened to records all the time and picked out people he liked and then he's have his assistant round them up and he'd put them in the studio and use them to make records. I'd never met him but I got a call one day from somebody at A&M who said he wanted me to come and play on some Joe Cocker Records. I thought it was a good opportunity to produce some songs, so after the session I played those songs for him and we cut them.

MR: So you moved from The Wrecking Crew into the Shelter People.

LR: Yeah, it's odd, I'd never heard that section referred to as The Wrecking Crew, that was the name of a somewhat mediocre Dean Martin movie which I didn't play on, although some of those guys did. I never heard the section named that until Hal Blaine's book. But what was the question?

MR: It's almost like that Joe Cocker album was the big step to you becoming Leon Russell the solo artist, or at least the duet artist with Marc Benno.

LR: I suppose so. Like I said, I met Denny doing those Cocker sessions, so when I played those songs I had a meeting with him later and I said, "Yeah, I've always wanted to have a record company, sing and do all that stuff," so we formed Shelter behind that conversation.

MR: You had a number one country record with Willie Nelson and you've easily slipped from genre to genre, is that because you just see it as making music?

LR: Well some people, for example program directors, are much more aware of genres than people like me. I'm not much on french words anyway. But I just never thought of it that way. When I was playing in the section in LA, they were talking about how Nashville guys are always ready to play. They have a conversation for about five minutes, write a bunch of numbers done, and when they're ready to record it they're very fast. I'm very fast myself. One day, I was taking a car back from LA to Tulsa where I was living at the time and I went into a truck stop and there were about a thousand country CDs in there at like three dollars a piece. I'd never been in a country band, and I lived in Tulsa. It wasn't until I got to California that I got in one. There are actually more hillbillies in California than there is in Oklahoma. But I bought a hundred dollars worth of those songs and listened to them on the way home. I got to thinking, "If those guys are that quick and that ready to play, I'm ready to play." I just picked out twenty six songs that I knew, not that I'd necessarily ever sung before. Sometimes the first time I sang them was on the session. Sometimes when I'd heard several different versions of them slipping from one track to another is really kind of embarrassing, but that was the origin of that.

MR: When you had a number one record with Willie Nelson did you think, recording country music had kind of paid off?

LR: Not really. I met Willie at a time when my profile was somewhat higher than his. He said to me one day, "You know, we ought to make records. We'd be the biggest thing in country music." I thought he must have been kidding. I didn't imagine myself as a country artist, I didn't know much about it. But later when he was on Columbia, he asked me, "Let's do this duet album" and so perhaps he was right, I don't know.

MR: And of course you did the duet album with Elton John. The Union was called the third best album of 2010 by Rolling Stone. That's pretty impressive.

LR: Yeah, I'm glad that they liked it.

MR: So far, you've had an amazing and varied career. When you look at the contribution that you've made to music, is there something you'd like to be known for?

LR: Well I don't really think of myself in the third person. To me, it's a different point of view. I'm happy to have a job. I play a little, write a little, perform some, it's not like it's an engineered, well-manufactured plan or anything. I just do what I do.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

LR: I think probably my main advice to new artists is if you want to be in the music business you, need to be dang serious about it because it's a rough business. It's what my uncle told me when I was going intol the music business. He was a great guitar player and a singer. He was a master sergeant in the air force for twenty-five years and ran gun clubs all over the world. When I told him I wanted to be a musician he said, "It's a rough a business." So that's my advice to them.

MR: Was it a rough business for you?

LR: Oh yeah, it was pretty rough. I started playing in night clubs in Oklahoma when I was fourteen. It was a dry state, and there were no liquor laws so consequently there were no laws about minors playing in night clubs, so I had the oppportunity to start early. I went out to California the week I got out of high school, I was seventeen, and found out that they weren't goign to have any sense of humor about that, they weren't going to let me play or even go into the night clubs unless I was twenty one, so I had to borrow IDs. The musicians' union wouldn't let you play--they called it "home stay"--they didn't want people coming into California and playing in night clubs, so in order for me to join the California union, I had to not work for a year. I said, "You'll have to explain what you're thinking about that." I had to borrow union cards and borrow IDs and if they had a different guy at the door who didn't know me and I'd already given my ID back to the person I borrowed it from. It was tough. I caught pneumonia out there and the doctors wouldn't help me in the hospital because I was a minor and I didn't have any adults so they wouldn't treat me in the hospital, but I got over it more or less. But it's pretty much a warring state out there.

MR: With your challenges over the years, did you ever feel like, "Dude, I've had it. This is it."

LR: Oh just about every other day. Like I said, it's a rough occupation.

MR: You're going to be touring for this album, right?

LR: Well I stopped for two years, but I've mostly been doing this kind of thing for forty-five years, so the public is more or less aware of me, I've been working the whole time and it's not changed. I play about a hundred and eighty shows a year.

MR: So the tour continues.

LR: Yes, it's a continuation.

MR: Is there a project that you're dying to get to? Do you look to the future and say, "I really have to do that," whatever that is?

LR: Once again, you're giving me the benefit of the doubt of knowing what I'm doing. I don't think of it that way. One day, I'll have an idea. For forty-five years, I've always had a studio in my house and usually live-in engineers so if I have an idea, I'll do it right there and it'll come out on a record. I'm not able to plan that far ahead, I'm sorry to say.

MR: So everything continues as it is until you just don't want to do it anymore.

LR: Yeah, I do that all the time. I really write more if I have a reason or a project or something, but about the time when I was doing The Wedding Album, I was getting upset because studios spend a lot of money and then sit there for months and months waiting for inspiration and I thought, "I need to be able to do this on call," like an accountant, you go to work, you do your job, you go home, eat dinner and go to bed. So I did a little bit of research when I was working on that album, I read a book called How To Write A Popular Song. It really helped me out quite a lot. I could probably write you one right now. That hasn't always been the case.

MR: All these years later, when you listen to your classic "Tightrope" what are your thoughts?

LR: Well, Edgar Winter said three out of five notes that I sang were out of tune and I said, "Edgar, don't hold back, tell me what you really think!" I can't really become too critical. I have to keep going.

MR: But it was fun to have to have such a huge, huge hit at the time, right?

LR: It's number eleven, it's the hugest hit that I ever had. I didn't have a lot of hits, actually. I was being played on what they called at the time, "Underground Radio." But I never had a song in the top forty pretty much.

MR: By the way, every time I hear one of your signature songs, "Roll Away The Stone," I still smile a little. And I'm sure there are many other lives that song and so many more of your others have affected, so I'd like to thank you, Leon.

LR: Oh, bless your heart. I appreciate it.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with Judy Collins

Mike Ragogna: So this love affair with all things Ireland has been in your life for a very long time. When did you first become aware of Ireland's beauty and history?

Judy Collins: I grew up with all of these songs, that was so extraordinary. My dad, who was such a great singer and a wonderful, wonderful performer had always sung the Irish songs. I grew up with them because they were in his repertoire. Not only he, but my godfather sang them, too. They sang "Danny Boy" and "If You Ever Go Across The Sea To Ireland" and "I'll Take You Home Again Kathleen," and all those amazing songs, so they were there in my life. As a matter of fact, I was quite sure that they must be Rodgers & Hart because all of the other songs that he sang, except for ones that he wrote, were Great American Songbook songs. So they were there, and the first folk song that I knew was a folk song was played on the radio and sung by Jo Stafford which is kind of a weird history because I knew her as this great singer of the Great American Songbook, and there she was on the radio on the record made by herself and her husband Paul Weston singing the songs of Scotland and Ireland. So that lured me.

MR: Can you remember which Irish songs you learned first?

JC: Oh sure, "Danny Boy" naturally. I knew "Danny Boy" before I could walk, probably.

MR: Where does the passion and the connection you have to this come from?

JC: I think there's a certain spirit of the Irish music, and of course you get to know all of the poets, I recorded William Butler Yeats' "Song Of The Wandering Angus" on my second album. I think maybe that song was written by Burl Ives, the melody-- I once asked Will Hope, from whom I heard it, "Did you write that?" He said, "No, no, I didn't." I think that Burl Ives probably wrote it, but during a time when people were afraid to take any kind of copyright rights on their versions of things that were considered either traditional or from other resources.

MR: Right. Do you look at how how Irish music has been passed down and evolved through the generations?

JC: I think that the Irish tradition has flooded into my own music, all kinds: the kinds I write, the kinds I listen to, I think it's very much a part of pop music because I think the tradition of Irish song really entered into the mainstream of Irish music a long time ago. There are a lot of roots there that we don't even know about which are hangovers from "Danny Boy" and "The Rose Of Tralee" and Molly Malone. I think they're there whether we can see them or not.

MR: You have a few guests on this album, such as Mary Black, and you have Emily Ellis.

JC: Isn't that wonderful? That's on a song I wrote called "Grandaddy," which is about one of my Irish grandfathers. She's a lovely young woman, and Mary Black is a very famous singer of Irish songs, she's known all over the world actually. She's famous, she's wonderful, she's a gifted artist. I was lucky to get her on the show.

MR: There are a couple of songs you're known for that are on this project, material like "Chelsea Morning" and "Amazing Grace." But "Bird On A Wire"...it seems the Leonard Cohen songbook slips very nicely into this genre, as well as Harry Chapin's "Cats In The Cradle."

JC: I know! I think again that there is this tradition that seeped into Canadian songwriters, Leonard, of course, being the Canadian whose songs I've recorded the most of, but I do think the connections are very strong. With "Chelsea Morning," Joni is another Canadian who had, I think, tremendous Irish influence in her writing and it's different; it has a kind of freedom in the writing that is a little different. With Leonard, of course, it's what charmed me into being able to write my own songs. There's a new song of mine on this project called "New Moon Over The Hudson," and that's really about the Irish diaspora, but it also goes into my actual story. You know my father's father's fathers came from Ireland shores, and they fought in Lexington and also the Civil War on the Union side, by the way, and died for the country. That I was not really sure of until recently; I have a geneologist who helps me locate these pieces of history in my own background. I'm very happy with that song, I think it reflects something that I've always been getting at, which is that family bond of poetry and music and lineage that has always been there.

MR: It does seem to be entrenched in American culture more than it acknowledges.

JC: Yes, absolutely.

MR: Do you keep an eye on Ireland both culturally and politically?

JC: Well, to some extent. Of course, we know about Ireland's troubles lately and about her troubles in the past and about her political problems and her history, I know all about her history. My father was so vehemently Irish that he didn't want to hear the name England spoken in the house. He was rampantly anti-England, although he was half English himself. Go figure. But he was mad as hell and with good reason. Of course, now everyone is getting over that antipathy and getting along. I did have the experience of going to Quinnipiac University up in Connecticut. The University has the only museum of the art from the Irish Hunger in the world. It's very powerful stuff, really deeply upsetting and disturbing, but also very beautiful.

MR: Have you ever been tempted to record a concept album around Ireland specifically?

JC: No, I haven't, but maybe I will, who knows.

MR: I was just wondering if it's tempting.

JC: Yeah, I think now we have to celebrate the music and the verse and the beauty of the Irish spirit over all and try to get beyond the antipathy and the rage of those years. It was brutal.

MR: There are other songs like "She Moved Through The Fair," which depicts a different kind of Ireland.

JC: It's the heart of Ireland, really, it's the beauty of their ability to tell stories and to connect nature and music. It was so beautiful to be there in Dromore because it's in County Clare, and it's just a beautiful place. It's so physically beautiful and that castle is just strikingly gorgeous. It's funny because "The Gypsy Rover," which I learned from the radio, I never did record it until too recently--it was at least forty years before I put it on a record of any kind. I think I put it on the Live At Wolf Trap album in 2000. I hadn't recorded it in all the years that I had known it and that's a funny thing because it talks about this young girl who runs off with a gypsy and when he reaches his home, it turns out he lives in a castle. So I finally got to the castle this time around.

MR: Ever since I saw that first shot of you with The Clintons, it's seemed more and more like you're a musical diplomat.

JC: [laughs] I think that's true. You can say anything in music and you can say it any language and in any country without compromising either your dignity or your political integrity, I think that's very true. It's a fortunate mantle that either I developed or inherited or created or taken on or something, but it's true. Music is the language of the heart and it travels very well.

MR: Are you watching younger artists and feeling this music is in good hands?

JC: Oh yes, and I have on my own label a number of artists who are honoring the tradition, people like Kenny White and Amy Speace who's going on to other kinds of things, but she's going to be in concert this year and so is Kenny White and Walter Parks and Ari Hest, who's a marvelous young artist, he's on the show of course doing a duet with me on one of his songs, "The Fireplace." So I think yes, it's in good hands and there are wonderful young artists writing about interesting and topical and certainly heartfelt new music about life and politics. Noel Stookey has this contest called "Songs To Life" and it focuses on politically sensitive songs and all kinds of wonderful things and I'm a judge on that, so every once in a while I'll pull out a song like the one I sang on the last PBS special called "Veterans' Day," which is a duet with Kenny White. It's about war and about veterans and about the universality of veterans and how everybody's got a veteran in their culture, and they're all on both the wrong side and the right side of history in a way, because they're in conflicts which wind up being essentially human without any tag of nationality. That's what we do, we fight and sometimes we win and sometimes we surrender and if we're lucky we start to get to the negotiating table before we get to the battlefield which is to be deeply desired.

MR: What are your thoughts on the tensions between the US and Russia?

JC: Well, it just makes me sick. That's how I feel about it. I think it's pathetic and human and upsetting.

MR: Throwing a non-sequiter out there, what advice do you have for new artists?

JC: Be careful what you wish for. It's the same advice I would give anybody in any arena of life, but I think it's not for everybody, that's for sure, but you have to do it of course if it's your passion, but be prepared to miss lunch. To be a dreamer you have to be realistic and to be a dreamer whose dreams come true you have to be extremely fit, so keep your stuff together and don't go too far out of bounds because the body that you're singing with today might have to last your fifty years.

MR: Judy, are you still a dreamer after all of these years?

JC: Oh absolutely. Absolutely, in the biggest kind of way. I have very big dreams and I don't miss lunch, but that's because I really do prepare. I don't let things take me by surprise.

MR: Well that's perfect for my last question: What does the future hold for Judy Collins?

JC: Right now, I am deep in the throes of Stephen Sondheim songs. That's the next big project for PBS.

MR: Judy, you also seem to be a PBS diplomat.

JC: [laughs] Oh, I love PBS. I'm bonded at the hip with PBS as we all are for all of the shows we want to watch, from Downton Abbey to The Eagles' live reunion. They're just the best. They do for music what we really need and they do it so well and at this point in our lives, most of the artists who survived the sixties and went on to thrive and concertize are the latchkey to the garden because they get music out for people. It's hard to reach people now, there aren't any music stores. I was in the Amoeba store in LA yesterday signing the new album and the new DVD and it's huge. It's acres and acres of DVDs and CDs and vinyl and every artist you've ever dreamed of seeing or hearing...and of course, they're one of a kind. Those places don't exist anymore, anywhere that I know of, anyway. So PBS is doing what we couldn't for ourselves. It's providing us with a platform and an avenue to get out to our audiences and we're very grateful for that. I love PBS.

MR: It's curious how they want to pull back funding from PBS periodically.

JC: Are you asking about why the government doesn't support the arts?

MR: [laughs] There you go!

JC: [laughs] I look at the sixteen days that we didn't have any government and I think my old friend Lingo the Drifter in Colorado used to have what he called his "Dormant Braincell Research Foundation Speech." During those sixteen days, I thought I should go down to Washinton and give Congress that speech, because what a bunch of idiots, excuse my French. Where are their priorities and what are they thinking? I guess I don't have to go too far to tell you where my politics lie.

MR: Beautiful. You're very consistent after all these years.

JC: After it all, I am consistent.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with John Gorka

Mike Ragogna: John, it is a pleasure. I have always wanted to have an interview with you. Your new album Bright Side Of Down features some label mates including Michael Johnson on the first track. What went into this project?

John Gorka: I think the approach was a little different from other albums I've done. Probably one of the things that makes it different from the others is that instead of trying to do it all at once or with deadlines in mind I wanted to do it a little bit at a time, mainly building around my vocal and guitar performances and then trying to see how the songs and performances held up over time. I was just kind of living with them for a while so that I could hear them with some kind of objectivity, like a listener who wasn't involved in the process.

MR: A lot of artists' work ethic while constructing an album comes from not only set deadlines but also because it's just traditionally the way it's done, in one scheduled run. But there's something to be said for savoring the material and letting it grow and letting you grow along with it, because there will be changes that may come down the pike affecting perspective, right?

JG: Right. There were lines that I wondered about going into it and then as I listened to them down the line I said, "Okay, yeah, that does need to be changed." I wanted to do it like the last one, which was also built around the vocal and guitar performances, because that's how people see me most of the time, always solo. I wanted that to come through the recording. This was the longest time it ever took me to make a record. I'm happy with how it turned out, but I don't know if that's the way it will be next time. One of the things about this group of songs, I wanted to have it really reflect the vocal and guitar performances because I can play with other people but often it'll change what I do. Sometimes that's a good thing and sometimes that's not, so to find my zone on the song and build around that was kind of the goal, but things change. You go in with one idea and it changes along the way.

MR: This is your fifth album working with Rob Genadek.

JG: That sounds about right, yeah.

MR: And you've included many of the same musicians on this project. Even though this was a very introspective process, it's nice that you still remain loyal to your session players in addition to your bringing in new cats. What is it that they bring to the mix for you?

JG: It's kind of fun, Rob always picks good people. He's never recommended somebody who's not right for the part. Bringing some of these guys in who I've worked with over time is a lot of fun because they bring so much to it, they have so many ideas and it's just a matter of choosing which ideas to use. They're really lots of fun to work with. Jeff Victor, the keyboard player, is hilarious. They're all great people, so it was kind of fun. I just know that these are great musicians and they can come up with any number of ideas. Beyond that it's kind of like "Make it up as you go along." There's never any real grand plan going into it other than what I said about having the vocal guitar be featured.

MR: Can you tell us what some of these guests, such as Michael Johnson, added to the project?

JG: I've gotten to work with Michael and travel with him. I was a fan, I got his record at a used record store when I was in college or shortly after college, I got his album called There Is A Breeze. I've been a fan ever since then and when I got to see him play live, he's just a phenomenal guitar player as well as a great singer and he's got great, great stories. So just having these people, they bring all of their talent and experience to the studio. It was kind of a delightful thing to work with them. Some of the others, like Claudia Schmidt, I was glad we had this song for. The percussion was made up of Rob, who's a drummer as well as an engineer and producer, and he made sounds hitting various parts of his body as well as tapping his foot on the floor to make kind of a groove that everything played to. We had this long fade at the end and I wondered what to do with that. Claudia came in and sang three parts one after the other and then she did a free vocal at the end and it was really great to see. I knew she was capable of doing that because she's so talented, but she even exceeded my hopes with her performance on that one. I'm glad to have these people on there. My hope is that maybe some of these people have not heard Claudia before so they could now check out her music.

MR: It must great to be part of a musical community.

JG: Yeah, I was glad to have all of these mainly Red House people; the players and singers are all great. They're maybe not celebrity cameo appearances but they're still some of the best people I could hope for. I was glad to have so many Red House people on there, like Amilia Spicer singing on a Bill Morrissey song because she's a good friend of Bill's, and having Antje Duvekot sing on the last song. Again, she came up with parts that I couldn't believe. She just sang it to her computer at home and she sent along what she had come up with and I was knocked out by it. But she couldn't figure out how to get those parts out of her computer so she did go to a studio and re-did those. It's a remarkable vocal arrangement, what she came up with.

MR: Since 1987 with your I Know project, you've had a very prolific relationship with Red House. You went to Windham Hill High Street for a while, but all of your material is at those two labels. When you look at this body of work, what do you think as far as John Gorka's career? Are you on target with where you wanted and now want to be?

JG: My goal, I guess, was to be able to make music and discover the music that was inside me. If I could do that for a living, that was my goal. Beyond that, I've not really thought that much about it. I'm grateful that I get to do music and I get to make records and travel around and people show up. That's a lot of fun and it's more fun now than it was in the beginning. But beyond that I'm not sure. Mainly I just wanted to play, and my goal now is to get kids through college and I can play as long as I'm healthy. I guess those are my short- and long-term goals.

MR: What is your advice for new artists?

JG: I was focused on my songs and the live show, but I'm kind of learning from new artists how they do it. It's harder now. With Red House and Windham Hill, I was able to reach a large group of people all at the same time, so I was able to have a base to build on. For new people... Some people are great at doing the online YouTube videos and stuff like that. Antje Duvekot is one of those people. She's kind of a next generation after me, and she's able to do YouTube videos, she recently did an animation where she drew all of the backgrounds and created this very low-tech animation using her iPhone. The track that she recorded sounded like a record and she sang that on GarageBand through her computer. So I think the main thing is to concentrate on good material. My general philosophy is high standards, low overhead, realistic expectations. So don't put out a record until you feel like you've done the best you could. Don't put out stuff just to put it out. There's a line in Suze Rotolo's book about Greenwich Village growing up in the late fifties and early sixties; she was Bob Dylan's girlfriend for a while, she was on the cover of the Freewheelin' album, she said, "The difference between then and now is we had something to say, not something to sell." I thought that was great. The main thing is to have something to say first and then do your best to make it as easy as possible for the world to find you. There's a lot you can do on the internet now. I was just reading a story in a guitar magazine about an acoustic guitarist who put up YouTube videos and became very well-known, so I think that would be a good way to go. Other than that, for the acoustic singer-songwriter a few of these festivals have emerging artist showcases and contests. The Kerrville Folk Festival has that, in Kerrville, Texas, the Rocky Mountain Folks Festival has that in Colorado, the Falcon Ridge Folk Festival in New York State, there are all these places you can send stuff to and then if they like it you can come and play those songs. Other than that, the thing is it's a very different world from when I started, there were record companies and record stores and ways of reaching a large block of people in a short amount of time. Now everything's very fragmented and it's difficult to get known. You can make a lot of music on your own, you can make records and potentially reach a huge number of people, but since everything is kind of fragmented and compartmentalized it's difficult to reach that critical mass of people. That's where record companies still have a role. Red House still does what they do better than I could ever do, so I'm glad to be able to work with people who care about the music and know how to get the word out.

MR: I'm especially fond of "Holed-Up Mason City" because it's the story of you driving through Iowa--I'm in Iowa right now, so I get the story. So did it actually happen, you getting blinded by the snow here?

JG: Oh yeah, yeah! I had rented a minivan because my daughter was having a tubing party with a bunch of her friends because we had two vehicles and one of them wasn't large enough to transport all the girls who were coming. So the plan was when I went to drop my batch of girls with their parents I would then begin to drive towards Iowa because there was a storm coming on. It turns out that the storm started that night. I was able to get to southern Minnesota but it was already terrible, it was icing over the windshield, so it was really difficult to see. On the day of the show, I stopped north of Des Moines because I wanted to drive partly back after the show. I was able to get to the show and it snowed and snowed all of that time. When I came out they asked, "Where are you staying?" I was about twenty or thirty minutes north of Des Moines and they said, "Oh, you'll never make it. You'll end up on the side of the road in a snow drift." So I took their advice and ended up getting a second hotel room and in the morning I was able to get back to my first one to get all of my stuff and head home. That's when it really started. It had become more of a ground blizzard and the snow was heading out of the west. It was a wicked wind, and like in the song I found out that the van I rented had no snow tires, they were all-weather tires, so I'm moving sideways seeing people flying past me on the left, so I pulled over to the rumble strip with my flashers on and eventually I thought, "This is not going well." So I was able to get off the interstate and headed towards what I thought was a town. Some of the roads I took I had to turn back because they were drifted over. Five foot drifts covering the roads. Eventually, I made it to Mason City. I ended up staying there and then I realized that that was the airport that Buddy Holly and his friends had flown out of in 1959. That's how he ended up in the song. There is no Big Bopper diner in Mason City, but I did find out later that there is a Big Bopper diner in Solvang, California. Eventually I was able to make it home. It was kind of funny because there was still ice on the road, but also a blue sky by then. The blue on the sky was reflected on the ice on the road, so that's where the "ice blue highway" line comes from. It's a pretty scary ride.

MR: I also wanted to mention another highlight of the album was "Don't Judge A Life," your tribute to Bill Morrissey.

JG: Yeah, I was at a folk festival and we had just done a set of Jack Hardy's music...he had passed away March of 2011. I sang at that and his kids were there and his ex-wife, so I was glad to be a part of it because Jack was somebody who encouraged me when I needed encouragement the most. The next day, I got a call from a friend telling me that Bill Morrissey had died, so I started it right after that. Since then, that song also applies to other people that have passed, so I'm glad to have that on the record.

MR: After all these years, you've got this reputation for being the songwriter's songwriter. So where do you go from here? Do you just keep getting better and better or something?

JG: I guess it's one song at a time. When I forget how much work went into this record I'll start the next one. I'm thinking maybe May. I've got some other songs I'd like to record. There's some from this project that didn't make it onto the record. I liked them well enough, but they didn't go together as well as this batch seemed to go together. One of the things I've been doing lately, instead of thinking I had to write a song for the universe I think about one place and one room, one group of people, one moment in time and have a song for that moment. Then if I can do something with that it seems like it makes it easier to come up with something new. I don't feel that it has to be for everyone and forever. It seems to free the process. If I can play with that a little bit to make it go beyond that room and that moment of time then I'll go about that, but that's kind of my current approach to new songs.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne