- in Uncategorized by Mike Ragogna

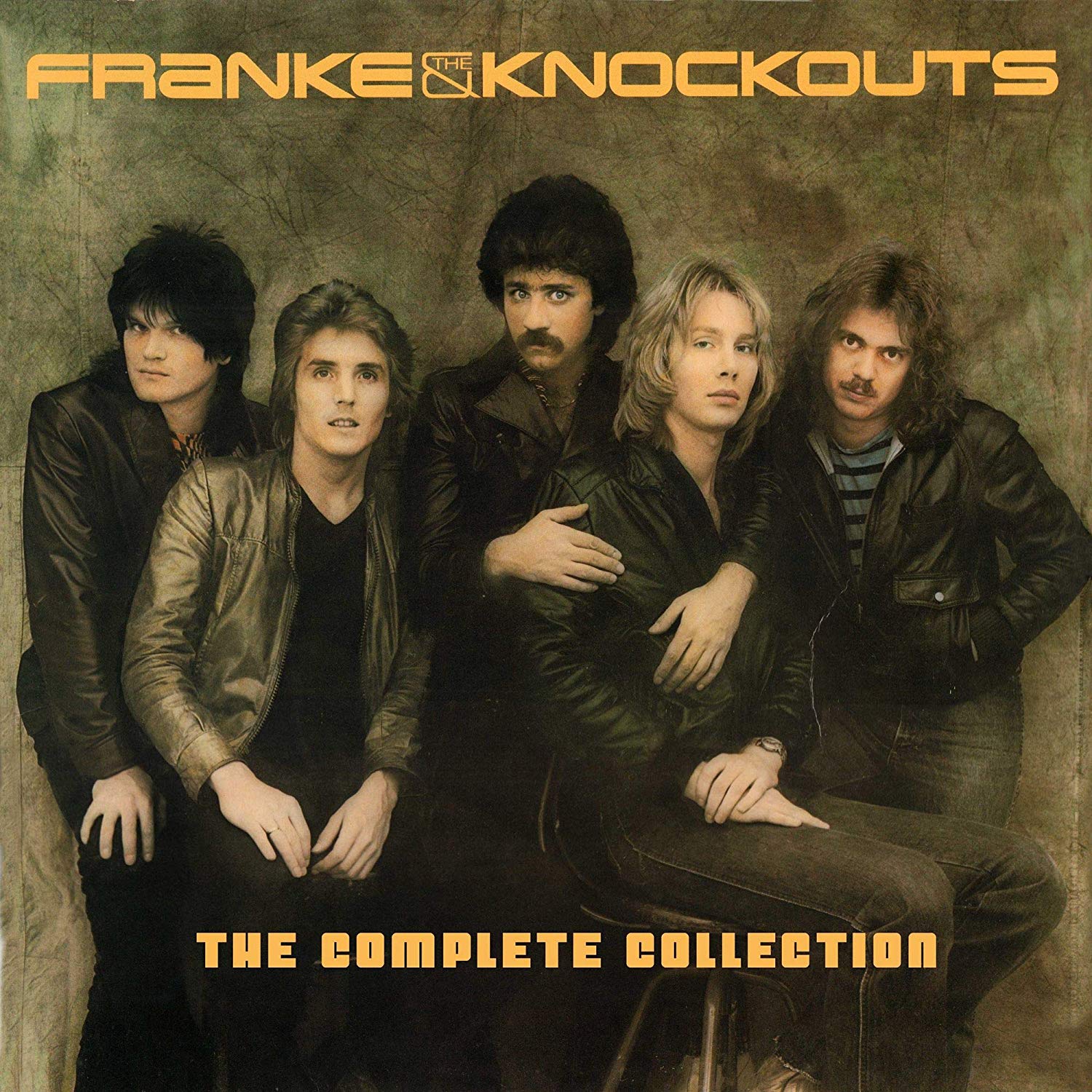

Having The Time of His Life: A Conversation with Franke & The Knockouts’ Franke Previte

Mike Ragogna: Franke, rumor has it you have a box set that has all of your Franke & The Knockouts material and beyond. What made up the package and how did the box come together?

Franke Previte: It really came together for a multitude of reasons. Joe Reagoso from Friday Music gave me a call and said, “You know what, there are the three records that Franke & The Knockouts did, they’ve never been released before as a box set, and that third record wasn’t on Millennium, it came out on MCA.” I said, “Yeah.” He goes, “That record really never saw the light of day and you’ve got some great songs on that record.” Yeah, that’s because when Jimmy Ienner closed up shop at Millennium, they (MCA) wanted us to sound like Night Ranger, and I was like, “Well why would you do that? You’ve got Night Ranger on your label, why do you want us to sound like Night Ranger?” They said, “Well, we would like to have Night Ranger’s producer come in and mix a single for you guys and let’s see what radio thinks.” They took a song called “Outrageous” and he did a mix on it and they sent it out to radio as a sample of Franke & The Knockouts. Radio was like, “Who’s this?” So the songs that I wrote that should’ve been the singles like “One Good Reason” or “Blame It On My Heart” or actually a song that was written in the same feel, 6/8, as “Sweetheart,” “Come Rain Or Shine” that Jeff Porcaro from Toto played on, they overlooked all those songs.They said, “Well, radio doesn’t like you guys, so we’re dropping you.” This box set gives me a chance to get that third record heard. Songs are like seeds that grow within you like children. Also, Joe said to me, “There’s plenty of room on this to put some bonus tracks if you have any songs that didn’t make the records or songs that you wrote when you were in Bull Angus, anything you want to put on here.” I put a musical history of the early seventies of me being in a heavier rock ‘n’ roll band that toured with Rod Stewart and Deep Purple and Fleetwood Mac and then I was an R&B artist on Buddah, so I took a couple of those demos that Tony Camillo, who produced “Midnight Train To Georgia,” did. Then I took songs that I wrote that didn’t make Knockout records and songs I wrote after I won the Academy Award for “Time Of My Life” that I wrote with Mark Rivera from Billy Joel’s band, and Kasim Sulton from Utopia, Todd Rundgren’s band. There’s a really cool mix of my history of me as a songwriter, and you can see how Franke & The Knockouts got created from this heavier rock thing to this R&B thing to this blue-eyed soul, rock ‘n’ roll band.

MR: “Sweetheart” was a kind of afterthought, no?

FP: Jimmy Ienner said to me, “Are you sure you want to put this song on the record? It’s really pop and radio’s gonna think you’re a pop band. You want to put that bullet in the gun?” I said, “Yeah, let’s do it.” After playing that song out with the band, it took on a whole other edge. It became a little rockier and a little edgier.

MR: The live material seems pretty revealing about the band.

FP: There are six live Franke & The Knockouts tracks on this box set, which I’m proud of because the band really kicked ass and it showed that we were really a rock ‘n’ roll band.

MR: I know the licensing world can be tricky so this must have been challenging. Did you own the rights to any of the properties or was this some kind of joint Sony/Universal project?

FP: I was able to purchase the masters so I own them.

MR: Did you have some foresight that you would want to do something with that material in the future?

FP: I never really had an outlet for those songs. They were always songs that were in my drawer, and I would put together a little collection of them if we were taking a road trip. I’d put five or six of those songs on a CD, get in the car, and play those songs for my own pleasure. When Joe said, “Hey, you can put some (more) songs on,” I was like, “How many?” “How many you want to put on there?” I’ve written about two hundred or so songs. I would just go through songs, try to pick an era, and try to think of a song that I enjoyed listening to, a song that I thought I sang pretty good on, and a song that helped guide the direction of who I became and who I am as a songwriter.

MR: How did “Sweetheart” come about and why do you think it turned out to be a little different from other Knockouts material?

FP: It was the last song that I wrote for the first Knockouts record. It was kind of an afterthought because we had already picked the songs. At that point, I was writing it about a father talking to his young daughter, that she’s the star in his eye. Jimmy looked at me and goes, “No. You’re not going to sing about that. You’re going to make this about a boy singing to a girl and she’s the light of his life.” I said, “Okay, I’ll tweak some lyrics.” I didn’t have to tweak too many but that’s what it was originally, a father loving his daughter. That’s me at the age of twenty-nine and most of my friends being married and having kids already, and me still being a rock ‘n’ roller and thinking I was missing out on seeing all my friends and relatives with their kids. I had a sentimental moment. When I brought it into Jimmy, he did say, “It probably is a hit record but it’s very pop.” When we rehearsed it with the band in the first two or three weeks that we learned the song, when you’re just starting to feel comfortable, the band is in a memory mode of trying to remember the song. When you play it in front of people, you start to realize that the energy you created for an audience is a much different energy than trying to play it perfectly in the studio. It has this little bit looser, rockier edge to it and we started putting kicks in the song that weren’t in the recording, like at the end of a recording, these little vibes, and we’re like, “Yeah, that’s cool!”

MR: I love that. Do you have a couple of other songs that you can give some background on?

FP: “Hungry Eyes” was written for the fourth Knockouts record. “She’s A Runner” was a story I wrote about somebody that was in my life at the time, somebody that I loved and cared about, but she was kind of scattered. She had a chance to be something great, but if you listen to the lyrics, she’s suffering from a bad case of blues, and she’s trying to get over it. She picks herself up because she’s a runner, but she’s a long way from home. She’s a long way from who she wants to be.

MR: How personal does it get when you’re writing?

FP: The songs, as you write them, especially for your first album, is almost like a greatest hits album because you had your whole life to get to that point to make your first record. Then it’s like, “Okay, you’ve got fifteen minutes, write a second record.” You’re on a tour bus and you’re writing with the band and you’re practicing new songs during sound check. We had this song on the second record called, “Never Had It Better.” We didn’t have any lyrics, we just had this jamming groove. We ended up getting an encore and the band goes, “Let’s just do that groove.” I go, “I don’t have any lyrics!” “Make up some lyrics!” So for that evening the song was, “Let’s Get It Together.” Usually, when I write a song, I have to find the melody first, and in writing that melody, phonetic words and sounds come out. When those happen, I usually record them or write them down because my inner seed is telling me that that G chord needs an “Ah” sound. So I’m jamming and I’m spitting out sounds, and sometimes, I’ll spit out a whole chorus. It’ll just come out of me. It wasn’t from an experience, it was just from a jam moment and my inner seed brought that out of me. The music made me create that.

MR: Do you find yourself versatile in your songwriting?

FP: I’m not a great piano player. My father was an opera singer so I’m more of a singer. Melody is my strong point. With lyrics, I really have to bust my ass and write and rewrite and rewrite. Sometimes when I’m starting to record the song, I’m rewriting it because I don’t like the way it sounds when I hear it back in the recording. Everything is a process and everybody has their own crazy way of figuring out the puzzle. You have prolific writers like Bruce Springsteen and Dylan and McCartney where magic happens for them and it comes out of them. For me, I’ve got to really work at it.

MR: Are they some of your favorite writers? Have they inspired you over the years?

FP: Really who inspired me earlier on because I come from that Italian opera background was listening to The Rascals or Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield (The Righteous Brothers) or The Temptations or The Four Tops, soul guys, because I was looking for the blue notes. I was hearing all the other notes at home.

MR: All the additions they make to chords, the fours and sixes.

FP: And nines–all the stuff an opera singer wouldn’t think to do because they want to be more articulate and on the point. Broadway singers, they’re another singer that I look at and they don’t have the blue notes for me. They’re too straight. I looked for these other R&B artists, blue-eyed soul singers, to really influence me as a singer. Stevie Wonder is an awesome singer and writer. If it’s good, I listen to it.

MR: Some of the proceeds of this project are going to the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network because of your relationship with Patrick Swayze.

FP: Patrick Swayze was a guy that I met at the Academy Awards and he confronted me saying, “Who sang the demo?” It was really important for him to know who the singer on the demo was. I said, “Why is that so important?” and he goes, “Because we filmed out of sequence, we filmed that last scene first and we filmed to that demo.” I said, “Well, I sang it with Rachele Cappelli.” He goes, “First of all, you’re the only one that did a duet and second of all, we listened to a hundred and forty-nine songs and turned them all down. We were getting to film that day to a Lionel Ritchie track that was a really good song but it wasn’t an original song that we could embrace as our own. When ‘Time Of My Life’ came in, I said, ‘We’re making the movie to that song.’ We hated this movie up until that day because we didn’t have an ending. After that day was over, we had such a phenomenal ending the camaraderie was a one-eighty, and we all said, ‘Oh my God, let’s go make a movie.” He said, “It really changed everything for us. The next day we filmed to you singing ‘Hungry Eyes.'” It was an interesting lesson for me to learn how they make a movie and it was also interesting to learn how much the power of music influenced those actors. After Patrick passed away from pancreatic cancer, I said, “I’ve got to do something, I’ve got to figure out a way to help.” I found out where Lisa Swayze was donating her energy and her time and money, and I found out it was to the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. I called up Pamela Acosta, not knowing who she was, and she happened to be the creator and CEO of that charity. I said, “I have an idea. I would like to take the original demos plus a song that’s now in the stage play Dirty Dancing called, “Someone Like You,” and I’d like to put them together on a CD and on Facebook. I want to sell them. Whatever money I make from them, I’ll donate to the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network in Patrick’s honor.” I’m doing kind of the same thing with this box set. I’m taking money from this box set and it goes to PCAN. Through the years, I’ve been doing this. Can you believe that Dirty Dancing was like thirty-two years ago? It blows my mind, man. Thirty-two years later, me selling these demos from my Facebook page, which is Dirty Dancing demos. I’ve raised about thirty grand for them. It’s important because Pamela told me pancreatic cancer is the least funded cancer charity by our government. I have this theory that if everyone in the world gave a buck, we could beat it.

MR: Beautiful. Can we talk about how those songs were created?

FP: Many years ago, Jimmy Ienner, president of Millennium Records closed up shop and decided he was going to go into the film industry. He went over and started working with Vestron Pictures, the company that did Dirty Dancing. So it’s two years later and Jimmy gives me a call and says, “Frankie, I’ve got this little movie I want you to write some songs for.” I said, “Really, man, I’m trying to get another deal, I don’t have time.” He says, “Make time! This is going to change your life.” I’m thinking, “Yeah, you’re going to change my life. You shut your label down, MCA dropped you, you’re going to change my life.” He says, “No, I’ve got a good feeling about this movie.” I said, “All right, what’s the name of the movie?” He goes, “Dirty Dancing.” My hand goes over my forehead, I’m thinking, “Oh jeez, Jimmy’s doing porn.” He goes, “No, no, man, it’s a cool little movie,” and he gives me this five minute description of Johnny meets Baby and the father doesn’t like the kid, and it’s in the Catskills but they end up together. That’s what I knew of Dirty Dancing.

MR: That’s some description. “Yeah, sign me up.”

FP: “I’m in, man, I’m gonna write you a hit record!” [laughs] He says, “The good news is, you’re going to write a song. The bad news is the scene’s seven minutes and the song’s gotta be seven minutes long.” I’m thinking I’ve got to write “MacArthur Park” here. He said, “Just try to come up with something. So I call John DeNicola, and he happened to be a songwriter I had just written a song called “Hungry Eyes” with. John was a bass player and he sent me a track, and I wrote “Hungry Eyes,” which every label turned down, by the way. I said, “John, we have a shot here at a song in a movie, it’s got to be seven minutes. Why don’t we start this song with the chorus up front and we’ll do it in half time and then on the verse we’ll double time it. It has to have a little bit of a Latino groove to it because they want to dance to it.” So John sends me a track, I play the track over the phone for Jimmy, and he says, “I like the track, make it a song.” I’m on the way to the studio to finish up another song, I’m on the Garden State Parkway exit 140 paying the toll, and I’m listening to the cassette and going, “na-na-na nime of my life–what the hell am I saying?” I’m scribbling “Time of my life…” on an envelope, going off the road. So the seed, that “na na nime of my life,” phonetic thing that I do created “Time Of My Life.”

MR: You were given footage at some point to complete the thought, right?

FP: No. Zero. I knew nothing. Patrick said to me, “It’s amazing that you wrote these lyrics. It’s like you were here watching through these lyrics. That’s how close and how relatable these lyrics are to our story.” The man upstairs wrote that song, really. Think about it. I had nothing to do with it. I was the conduit.

MR: When each of the recordings were played back to you, what did you think?

FP: My reaction was, “Bill Medley! Icon!” I got Bill Medley singing one of my songs so I was thrilled. I was also told by Jimmy Ienner that I could sing “Hungry Eyes.” I had set up a whole recording date with all of the players, I was getting ready to play the song, and then Emile Ardolino who was the director, called me and said, “I need another song, can you come in?” So I went into New York and I’m watching this other scene, and he said, “Oh by the way, what are the bpms (beats per minute) for ‘Hungry Eyes’ because they’re having a hard time linking it to your demo.” I’m going, “What are you talking about? I’m recording it Monday.” He says, “Oh. Bob Summer was just hired as president of RCA and he just signed Eric Carmen. You’re out and Eric Carmen is singing the song.”

MR: God. Welcome to entertainment.

FP: I’m like, “Okay, I’m good with him, he’s a good singer, but jeez, somebody oughta give me a heads up. I’ve got some recording time and I’ve got to make a lot of calls now and tell everybody that there’s no gig.” I think Eric did a great job and I’m thrilled to have both of them singing my songs. I think it would’ve rekindled my Franke & The Knockouts career but I think it also helped Eric Carmen and Bill Medley rekindle their careers.

MR: Personally, I think “Hungry Eyes” might be Eric Carmen’s best recording.

FP: It’s funny because there was a bit of a back-and-forth with Eric. When people start to listen to demos, they get what I call “demo-itis.” “Eric, can you do that little turn Franke does?” “Dudes. It’s me. I’ll sing it my way. I’ll sing the melody but I’m doing my turns.”

MR: Let’s talk about some of the other material on the package like the previously unreleased bootleg live recordings referenced earlier and the demos. Do you have any info on the studio demos?

FP: There’s a song that I have from Bull Angus called “Sweet Marmalade.” The recording is from back in 1975. It was a demo, a one-take winger, throw whatever vocal you were using as a guide on it and we’ll keep that. We were just collecting songs to do another Bull Angus record. We had already done two records so this would have been our third. That group broke up so we have that song on there. Then the songs from the Tony Camillo era, the Buddah Records era… One is called “Never Gonna Leave LA Again” It was kind of a blue-eyed soul song. Every time I wrote a rock song, it went in Tony’s drawer. If I wrote an R&B song, we recorded it.

MR: What was it like working with Tony Camillo?

FP: Tony became my mentor along with my dad, because I would sit there and watch him producing other people’s tracks. His studio was in his basement in his home. You’d walk in this small little ranch and he’d take you downstairs into this major studio, and you’re like, “Oh my God, what is this doing here?” That’s where he recorded “Midnight Train To Georgia” and all of these great records. He’s a Grammy award-winning producer. He produced me and I went to school. I learned a lot from Tony Camillo. Then there are songs on the box set like “Desperately,” on which you can start to hear “Franke & The Knockouts,” the blend of Bull Angus and R&B. “Desperately” has this taste of Foreigner in it. There are songs that I wrote with Todd Rundgren’s Utopia, Kasim Sulton, who was the bass player, and Mark Rivera. There was a song called “Imaginary Line.” Then there are a couple of songs, “Faded In The Night” and “Heartache Avenue,” which were just songs that I wrote with Billy Dietrich who was a writer that I bumped into. He had a couple of tracks and I would write a song with him. These were all songs I was collecting for the next Franke & The Knockouts record, songs that I thought deserved to see the light of day and that I thought I was singing well.

MR: What about the live material?

FP: The live material has “Sweetheart” on it, it has “Without You,” it has “Never Had It Better,” it has “One Good Reason,” and “You Don’t Want Me.” There’s a song from every album on there.

MR: And that’s all from the various tours you were on. You toured with bands like Fleetwood Mac and other heavyweights. Are there any guests from those bands jumping in on the recordings?

FP: Tico Torres plays on a lot of those live tracks but he was a member of the band so you can’t say he’s a guest. But he was the drummer for Bon Jovi. Leigh Foxx was our bass player and for the past twenty-some-odd years has been playing in Blondie, Debbie Harry’s band. They’re not guests, they were band members, but they were guys who went on to do other things. Bobby Messano was in that band, he played with Stevie Winwood and a lot of other people. He has his own blues albums out now. The other guys are out there still being musicians, doing what they do. I kind of lost where Billy Elworthy and Blake Levinsohn went to. They were on two original pieces that I wrote, “Sweetheart” and “Annie Goes Hollywood,” a couple other songs like “She’s A Runner.” I can not find them. I tried to reach out to them on Facebook, reminisce, where you been? But I can’t find them.

MR: Franke & The Knockouts’ roster evolved over the years. What was the core and how did the policy of other people coming and going begin?

FP: The core of the band was Billy Elworthy the guitar player, Blake Levinsohn the keyboard player, Leigh Foxx on bass, the drummer was Claude LeHenaff and me. As we started building the songs in the studio, Blake really was more of a piano player than he was a synth or colors player. Because I had played with him before, I asked this guy called Tommy Ayers from Poughkeepsie, New York. Tommy Ayers was and still is one of the best keyboard players I ever played with. He came in and I asked him to join the band. He said, “No. I don’t want to be on the album. I’ll play on the album but I don’t want my picture on the album.” I said, “Okay, well, come on in and play because you play great and I want your sound on there.” Claude LeHenaff was from Poughkeepsie, New York, and I knew him from that area because Bull Angus used to live up in that area. I knew where those players were, who to ask, and who were the good players. I brought those players in. There was no Franke & The Knockouts. What I mean by that was I was writing with Billy Elworthy. He and I lived in an apartment in New Brunswick and I was selling cars out of a driveway to make ends meet. Billy would go into the city and play with Cherry Vanilla and some (other) band. He said, “Let’s add this keyboard player, I think you’d like him, he may have some good songs.” When Burt Padell, who was the accountant to the stars–like Madonna and all those stars–I met him and he took my demo and gave it to Jimmy Ienner. He did in three weeks what I couldn’t do in two years. When I met Jimmy Ienner and he said, “I really love your voice and I think these songs are really good, do you have a band?” I was like, “Sure, yeah, I got a band,” and it was just me and Billy, really. After I grabbed all these guys and said, “Let’s go do a record,” there was no endings to songs. It was just us for the next six weeks in the studio rehearsing and putting some songs together. All these guys went on their own way after the record came out. All of a sudden, “Sweetheart” starts going up the charts and Michael Kleffner, who was our music manager, called me and said, “There’s a show that’s called Fridays, it’s on Friday nights, it’s kind of like Saturday Night Live. I’d like you to watch that show tonight.” I go, “Why?” “Eh, there’s a band that I manage, Jefferson Starship, and they’re playing on it.” “Okay, great.” So I’m watching this show and at the end of the show, Larry David comes out and says, “And next week’s special guest, Franke & The Knockouts!” I’m like “Okay. I haven’t gigged out in two and a half years, there is no band Franke & The Knockouts, it’s me and Billy.” Michael calls me and goes, “What do you think, bud? What do you think!” I go, “Michael, there is no band.” He goes, “You’d better have a band by next Friday because you’re live on national television.” So I called the guys up, we learned “Sweetheart” and “Comeback” and put an ending on the songs. So our first gig was Fridays, our second gig was the next day, Saturday, on American Bandstand. Our third gig was Sunday, Solid Gold, and then Michael said, “In two weeks, you’re on tour with The Beach Boys. Put a set together.” That was Franke & The Knockouts.

MR: Awesome. Did you record anything new for the box set?

FP: No, I didn’t record anything new, because I had all of these other songs. I’m working on a project called Calling All Divas, which is a play that I kind of wrote. It’s a jukebox musical that the guys from Jersey Boys are sponsoring. I’m writing songs for that so they wouldn’t have fit on. It’s these four girls who are competing against each other to become the next super star, all at different ages of their career. One’s a gal in her fifties, one’s in her forties, one’s in her thirties, one’s a nineteen year-old girl that we find in a subway. They all compete to win the favor of this guy who’s going to break one of them to become a superstar. He can’t figure out which girl he likes best, so in the second act, he makes them a group called The Unforgettables. The whole second act is a concert of The Unforgettables. [Note: The show premiered in March at the Keswick Theatre outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.]

MR: Can all this action lead to something else, like maybe you performing out more or working on other kinds of projects? Is this inspiring you?

FP: The label has said it to me, “Why don’t you put the band back together? Why don’t you go out and play some of these songs?” Friday Music also has Utopia. He says, “Todd Rundgren’s selling tons of records, they’re back together and they’re playing out.” I said, “Let’s put it out, let’s see if the response from the people is good.” I tell you what, I’m pleasantly surprised that I’m getting a lot of reaction in England and places in the Midwest that really love Franke & The Knockouts. I had no idea because the label was always, “Eh, I know you went top ten but you’re not very popular in Europe,” and I found out that we really were.

MR: Franke, what is your advice for new artists?

FP: There is something that I live by and that is for anyone and everyone out there: There is a star in all of us. We just have to realize that. Eventually, if you keep believing in that… It’s not an age thing, it’s about a belief thing. It’s about staying the course. I can’t tell you how many times I got knocked down. The theory for me was, “Will I get back up?” There’s a star in all of us, just believe that and search for your star.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne