- in Entertainment Interviews , Thomas Dolby by Mike

A Conversation with Thomas Dolby – HuffPost 7.13.11

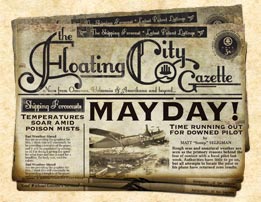

Mike Ragogna: Thomas, your new project is the transmedia game, The Floating City, that also connects to your music in a unique way. Can you go into a bit?

Thomas Dolby: The setting for the game is a sort of an alternative ’40s–sort of a dystopian vision of what Europe might have turned into had World War II ended differently. The game really combines all of the characters, storylines and places that have been in my songs right back to 1980. During the ten or twelve years that I was away from music, down in Silicon Valley, these news groups and forums started to flourish where people would analyze my songs and lyrics. They would take on the roles of characters in my songs in their handles and write this collaborative fiction based around the characters in those songs. I thought this was a great thing, but it was kind of limited to a hardcore audience of just a few hundred people. So, I thought that if I could expand this to thousands or tens of thousands of people, it might be an interesting and different way to set my music apart, and to introduce a new and younger audience to my music.

MR: Yeah, and once somebody gets into the topics and what you’ve done on your albums, they’re hooked. From album to album, you’ve always been very creative and detailed with your characters, images and storylines. Now, this game is online and free?

TD: Yeah, it’s free. You can do it with your browser–you don’t need to download software–you just go to floatingcity.com, and you can play in your regular browser. In fact, you can win cool prizes like MP3 downloads, and the ultimate prize of the entire game, which goes to the winning tribe, is a private concert by myself and my band, at which we will perform the album, A Map Of The Floating City in its entirety.

MR: A Map Of The Floating City being your next album. When’s it coming?

TD: It’s going to be a little bit later in the Summer, at the conclusion of the game. So, late Summer, early Fall.

MR: What a great idea. What has the response been so far?

TD: Well, amazing, actually. Thousands of people have signed up. The level of writing and role-playing is very, very high…very literate. It’s viewed by some as kind of steampunk-inspired civilization because there’s been some sort of terrible catastrophe on the planet, and we don’t know what it is. All that’s really left to the survivors are the relics of a former civilization, so they pretty much have to invent new technology themselves from the bits and pieces that they find. Because the temperature levels on the planet have risen so high, the only cool place to be that will sustain life is at the North Pole. So, what the survivors do is form into tribes, and they push out in the hulls of abandoned ships out into the seas and they raft up to each other until they eventually reach the North Pole.

MR: Thus, The Floating City.

TD: Thus, The Floating City. It’s a strange kind of barter community, somewhat based on medieval times in Tokyo Harbor, Japan. All the merchants used to bring their barges there to trade, and eventually there was gridlock. So, they just rafted up and it became this strange den of iniquity where you could buy silk and spices by day, and by night, you could buy almost anything you can imagine.

MR: So, does this floating city run into other floating cities, or other people that have had similar ideas along the way?

TD: Yeah, absolutely. There are three major landmasses left over called, Americana,Urbanoia and Oceanea. The survivors from each coast push north and eventually converge at The North Pole. One of the objectives of the game is to figure out what happened–everybody’s memory is kind of blurred as to what happened before the catastrophe. So, you have to piece together, with your tribe’s people, what happened that made the world go so terribly wrong.

MR: Are there clues that you’re wanting the players to pick up from the songs?

TD: Yeah. Going back to the first EP that I released from the album, which is called Americana, I’ve been laying clues. So, there was a clue in Americana, and then another clue in the second EP, Oceanea, which you need to go back and find. As I mentioned, it’s barter society, so you’re trading items from your cargo, and some of those items have special qualities to them. For example, you might find a page torn out of a scientific notebook with some equations and notes scribbled on it, and you have to figure out with the other people in your tribe what this means.

MR: It seems like a first of its kind. Have you seen anything like this on the internet at all?

TD: I’ve never seen anything quite like this. I mean, I’m not a gamer–I found a great team of game building engineers and designers, most of whom I’ve never met. In fact, I’ve never met any of them besides the main game designer, Andrea Phillips, who I met once in New York, but the rest of them I’ve only met on Skype.

MR: Wow, how does that work?

TD: We’ve been developing this thing for five months, and we just meet on Skype every day at the same time. We have what’s called a “scrum,” and we just set our objectives for the next twenty-four hours, the next week, or whatever it is, and we gradually developed the thing over time.

MR: So, there are about four or five of you working on this?

TD: Yeah, I think six, including the art director.

MR: Would they send just a screen to you with specifics or would they actually demonstrate how it worked for you?

TD: Well, it was always an online game, so we started building it online. I was able, while we were chatting on Skype, to go in there and actually play with what they’d done and make my comments. You know, I was pretty much doing it by the seat of my pants. I had a concept for it and with the game designer, we figured out a spec, but as time went on, certain things turned out to work really well, and other things just weren’t happening, so we had to be selective about what things we included. What Andrea kept stressing to me was that the players are incredibly intelligent and imaginative, and sure enough, as soon as we launched the game, I was just blown away by how into roles players got, the kind of storylines they were coming up with and how perceptive they were about the clues left for them. I probably underestimated their intelligence and their ability to be creative writers in their own right.

MR: When you look at, for instance, the Magic community, the level of character development and where they go with the stories is incredibly detailed. It must be satisfying to know that this is now being applied to something that you’ve created.

TD: Absolutely. I’ll give you an idea of one of the features we came up with. With the license that you have in your cargo, you’re able to combine them and file for a patent and you can use your patents, for example, to protect yourself from one of the weird, freak events that happens. Just the other day, there was an attack of rabid gulls, and you had to come up with a way to protect your vessel from rabid gulls and file a patent for it. Well, I put the button in there, and my plan was to announce how people should use this, but without any help from me at all, people started coming up with the most amazing inventions, using the items that they had. Not only that, they were also adding support in the documentation, such as graphics that they’ve done at deviantart.com or flickr.com–little diagrams or even Photoshop’d images of their inventions.

MR: Do players have to choose avatars?

TD: Yeah, you have an avatar and a screen name, and you get in your vessel, which is not a vessel you can go anywhere in–it’s basically an engineless vessel because there’s not fuel. The way you get around is by trading with other vessels. So, you hail another vessel, send them a raft-up request, and if they agree, then you end up alongside them. So, this is the way that the vessels gradually make their way north. If you work as a tribe, you can collaboratively move quite fast, but there are certain advantages to making alliances and doing inter-tribe trading because the other tribes have different items and different information.

MR: So, you’re playing with other partners online, much in the same way as Xbox?

TD: Yeah, and you can invite your own friends into your tribe. But when you initially sign up, you’re sorted into a tribe based on your geographic location. So, we divided the world up into nine tribes, and the reason behind that is that the winning tribe will get a concert in their general geographic area, and I didn’t want people to have to travel across continents to get to it. On the other hand, if you have friends in another country or continent and you want them to be a part of your tribe, you can invite them into the game. Most of what you do in the game, you have the ability to Tweet or put up on your Facebook wall, just by having a button checked within the game.

MR: Thomas, when you look at your body of work before this new record, are there songs that are full of clues? Is it good to know what goes on in your back catalog?

TD: Absolutely. The game involves all of my previous album, plus my brand new album. The way I started it, for example, is I made a database of every place and every character that I’ve ever mentioned in my lyrics. Then, we started to divide them up and figure out how we can combine them into tradable sets. A friend commented to me the other day that it’s as if every song I’ve ever written, going back to ’80, was a part of this big, grand scheme that I had up my sleeve. Of course, it wasn’t that way, but it certainly does fold together into a single timeline and brings a continuity to my body of work.

MR: Would you look at this as a closing volume of a big story arc then?

TD: I’m not sure that it’s a closing volume because, in fact, we’re going to sort of lay some groundwork for a sequel. I think that however successful The Floating City game is, a lot of people will only hear about it when it’s already over. So, we’re trying to create some kind of artifact that will remain afterward so it’s just not gone forever. This is something that is a slightly different discipline from somebody who is in the music world because if you make an album, then it has the potential to last forever. But with a game, it’s often a very transient thing and that’s kind of hard to stomach in some ways. I’ve tried to lay the groundwork for some continuing work in this area. So, no, I wouldn’t say it’s the close of a story arc, but it’s certainly a summary of my entire body of work to date.

MR: And it’s all self-released.

TD: It’s a self-release. In fact, to release this album, I’m revitalizing the label I formed in ’80, which is called Venice In Peril–aka VIP. So, A Map Of The Floating City is going to be self-released, and it’ll come out on my own label. I flirted with record companies, and I think I’ve really dodged a bullet in some ways because I think the record industry is in a terrible state at this point in time. I think when you weigh up all the pros and cons for somebody in my position, I think I’m going to be better off doing it myself.

MR: Yeah, that’s the whole DIY approach that everybody is resorting to. It seems like the days of the big record label and what they ultimately can do are more romantic than practical now.

TD: Well, I think they are. The flip side of it is that doing it myself has given me a slightly better appreciation of what record labels actually do from day to day. There are just a dozen different things you have to juggle at the same time, and nobody gets back to you promptly, there are deadlines, and it messes up your whole project’s schedule. It’s very easy for things to go off the rail. So, it’s given me slightly more respect for record labels now that I’m finding myself filling their shoes.

MR: (laughs) Do you have any advice for new artists?

TD: Well, I think you need a wider variety of skills than you did when I started out. You’re going to be competing with fifty-thousand other artists just like you, and in order to do that, you’re going to have to be very creative and think of new ways to promote yourself as I have done. I think on the plus side, I’d rather be competing with other artists on a level playing field than competing to get a cassette tape listened to by an A&R man, which was just the beginning in my day. That was just the beginning of the whole mountain you would have to climb before the public would ever hear your music. At least now, you can put a video up on YouTube of you singing into your laptop in your bedroom, and if you’re brilliant like Jessie J, for example, then you’re going to wake up the next morning and be a global superstar. I think that’s a much healthier state of affairs than when I first started out.

MR: Yes, the business definitely has changed, including the payoff.

TD: Yeah, the new payoff, I think, comes faster for some people because they don’t rely on the star-making machinery of the industry, which was so intangible. By the same token, there may not be billionaire rock stars living in villas anymore. I think that a much larger number of people will be able to make a living from music, and I think that is a healthier thing for the music itself. The stranglehold that was on music by a handful of companies is no longer there anymore. It’s really wide open, and it’s very inspiring to young kids starting out, and very conducive to a great new era of popular music.

MR: Plus you don’t have to rely on a handful of stations making or breaking you or your record.

TD: Yeah, it’s definitely a brand new age, and I think that I’m one of the lucky ones, in a way, because I’ve a leg up. I was very fortunate that I established a name for myself during that previous era and then I took some time off, and now I’ve come back and there are all these new tools available to do the stuff that I like to do, so it’s very exciting.

MR: Looking back at your career, how has the artist, Thomas Dolby, grown?

TD: I think the fact that I wasn’t out there treading the boards night after night, going straight from album to tour, and then back to album…I mean, I’ve had an amazingly varied career, given the people I’ve worked with, the variety of different adventures that I’ve had. Included in that, I would say the adventure of actually quitting in the early ’90s and spending time away from the business has enabled me to approach it with a freshness now that I’ve come back to it, which is something that I don’t think is shared by many of my contemporaries.

MR: Yeah, that’s true. Thomas, I don’t know if I mentioned this the last time we talked, but how I discovered your music was through New York’s big FM station, WNEW that played “Airwaves” often. That was the first thing I ever heard from you, and I felt like Steve Martin in The Jerk–“Oh my God. If that’s out there, I wonder what else is out there?”

TD: That was a blessing, really. A song like “Airwaves,” which was very moody, atmospheric, personal and cinematic, was so different from “She Blinded Me With Science” or “New Toy,” which I wrote for Lene Lovich, or “Magic’s Wand,” which I wrote for Whodini. Those were all quite extroverted, dance-y, accessible, sort of fun pop songs. I think because of the way the record industry worked, when they knew I was capable of that, there was no way they were going to get behind something as moody as “Airwaves.” They’d say, “Oh, come on Thomas. You can tune us out after more ‘She Blinded Me With Sciences’.” (But) people got into songs like “Airwaves,” “Screen Kiss,” “Budapest By Blimp,” “I Love You Goodbye”–those were the songs that they rave about on a daily basis on those internet forums. They don’t really talk about “…Science,” Hyperactive,” and the more poppy songs. I’m very glad that because I got mass exposure with those hits, it enabled people to get past that and into the meatier and more personal aspects of my music. What makes me sad is that because I made the label some money with something poppy, they were never really able to put their full support behind the more moody, personal stuff. So, one of the great things about today is that I’m only accountable to my audience and my fans, and if I want to put my weight behind those songs and not be entirely poppy and extroverted, then that’s entirely up to me.

MR: It’s a great creative freedom to make your own artistic choices.

TD: Yeah. Again, I’m feeling it and I think that artists all over the world are feeling it. They’re rocky times, for sure, in the music industry. But, ultimately, I think it’s going to be good for the music, good for musicians, and good for the fans.

MR: Any plans to tour when A Map Of The Floating City actually comes out?

TD: Plans? Yes. Fixed dates? No. Because I’m based in the U.K. now and I don’t have a label or manager or anything, it’s hard to pull these things together. I’m hoping to tour the U.S. in the Fall, I’ve got some U.K. dates set up in the Fall already–those are in November–and either the month before or after that, I hope to be touring the U.S. as well.

MR: Do you have distribution already set up in the United States?

TD: Yeah, I can’t go too far into that. As I mentioned, it’ll come out on my own label. I can get help from distribution companies, but certainly, I won’t be going the label route.

MR: This was really a pleasure talking to you, as always. By the way, like last time, I’m talking to you from solar-powered KRUU-FM, and you’re probably talking to us from your solar-powered studio, right?

TD: Yeah, you know all about my solar and wind powered studio. One of the gigs I’m doing in November in the U.K. is at The Big Green Gathering, on a stage which is entirely powered by renewable energy, so that will be a first.

MR: Beautiful. Congratulations on that. Thank you for your time, Thomas.

TD: Alright Mike, nice talking to you.

Transcribed by Ryan Gaffney