A Conversation with My Mentor, Tommy West – HuffPost 8.17.11

Mike Ragogna: Tommy! Finally, huh?

Tommy West: How’re you doing, Michael?

MR: I’m great, Tommy. Man, where do we start? Okay, recently I had the pleasure to work on a double disc set that includes Hometown Frolics, your solo album from ’76.

TW: Right.

MR: Now, Ace Records, in England has combined Hometown Frolics with Terry Cashman, your longtime musical partner’s solo album. Both the albums were fleshed out with bonus tracks and some recordings that were left off of earlier projects that were relative to them. Let’s start with that album, Hometown Frolics. Now, that started off being the fourth Cashman & West album, right?

TW: Yes.

MR: How did it split into solo albums?

TW: We had been together for about fourteen years, and we started writing for a fourth album. We were both going through personal changes in our life that were fairly meaningful. It was one of those things like when Simon & Garfunkel had to stop because they were going in different directions–Garfunkel wanted to make movies, and Paul Simon wanted to keep writing–so, it was inevitable that they broke up. We never broke up when we realized that our songs were going in two different directions. Cashman was more into urban, his stuff was grittier, it hit harder, and it was more pop. I had recently moved out here to the country, and I was an ersatz cowboy, so I was leaning toward country. We looked at the body of work and we said, “There’s enough stuff here for two albums. Maybe that’s what we should do.” I don’t know if it was a good decision or a bad decision, but that’s the decision that we made.

MR: Well, the two albums that were a result of that decision ended up being, perhaps, more focused than they might have been had you kept them together.

TW: Yeah, that’s a good way to put it.

MR: The Hometown Frolics album, for many, is a brilliant album. In fact, Trevor Churchill from Ace was so determined to put that out as opposed to putting out the more obvious material, which would have been the Cashman & West albums. He really loved that record and wanted to make sure that it had its day in the sun.

TW: That was really nice of him. We’ve become pals on the internet.

MR: Yeah, and it was great working with him. He is, of course, the overseer for a lot of projects that come out of the wonderful compilation label, Ace Records. Let’s explain the ersatz country thing. You moved out to Pottersville, New Jersey, from New York City. Pottersville is a kind of country town, which is something that most people don’t realize when they think about New Jersey.

TW: Right. It’s only fifty miles from the Lincoln tunnel, but it’s a world away in terms of the vibe of the place and scenically. It’s New Jersey horse country, and there are a lot of people out here whose major problems are cash flow problems. They don’t work.

MR: (laughs) Nice. And you still live on your 13 acre farm with a barn and horses.

TW: Well, we had horses for the first eight years, but when we moved to Nashville for a while we gave up the horses. Now, part of our acreage is available so that the horses that live next door can come over and graze on our property.

MR: Very nice. And to this day, it’s still country living, complete with a general store and everything.

TW: Yep, it’s like Norman Rockwell.

MR: Now, the front cover of Hometown Frolics features a certain couple of rascally kids.

TW: Those are my two stepsons, who, at the time, were about seven and nine. We used them on the front cover, which is the Oldwick General Store.

MR: That album came out right during John Denver’s arc of hits, and the mood in the US was sort of like, “Let’s get back to the country,” so it was a perfect time for that album.Hometown Frolics even featured a really great cover song, Ed Bruce’s “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys.” Wasn’t your single version of that song the inspiration for Waylon and Willie recording it?

TW: Well, they heard my version on the radio, and they copied my format, where I started with a verse, as opposed to Ed’s version where he started with the chorus. I could hear it in the background, as their record goes into the last chorus, they sort of tried to do what I did with the background vocals, but they either didn’t like what they did or they turned it way down.

MR: You also have “Old Radio” that relates to your childhood.

TW: When I was a kid, the radio was a constant companion. When my mother and father would fight, I’d go into the bedroom and turn up the radio. I can’t go to sleep without a radio on to this day. I keep one with a speaker under my pillow, and I almost have an anxiety attack if I’m on the road someplace and the batteries go out. I constantly have to have a radio next to me.

MR: Do you listen to talk shows or music?

TW: I try to find what the most interesting thing is on the radio at that time. If it’s a music show, like a music special about somebody, I’ll listen to that. If it’s a talk show with an interesting political person, I’ll listen to that, or if it’s a sports show, I’ll listen to that.

MR: Nice. Hometown Frolics, the title of that album was based on one of the shows you listened to.

TW: Very early, back in Newark, New Jersey, in the late ’40s, there was a station called WAAT, and they had a show with a guy named Lyle Reed. The name of the show was “Hometown Frolics.” It was an early afternoon DJ show. Then, another guy named Don Larkin took over his slot. It would start off with “Back In The Saddle Again” as the theme song, and my mother and I used to listen to that show every day.

MR: “Back In The Saddle” is part of a medley on Hometown Frolics with “Don’t Fence Me In.”

TW: Yeah.

MR: And there is also an Anne Murray-inspired song called “I’ll Sing For You.”

TW: Yeah, I wanted to write a song I thought Anne Murray could sing, and later we used the intro of “I’ll Sing For You” for “The Wayward Wind.”

MR: Making the connection even stronger, nice. “The Wayward Wind”‘s from her big comeback album, Croonin’, that you produced.

TW: Yes.

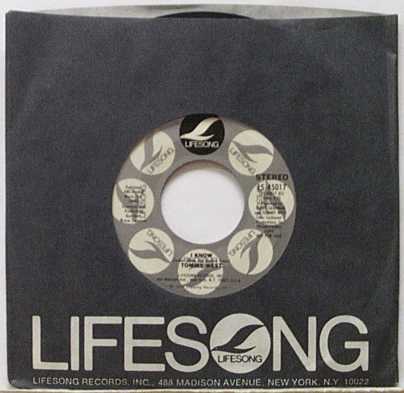

MR: Would you go into the story of your single “I Know”?

TW: Well, I have a tendency to get depressed a lot when I’m working. One day we finished early and I was there by myself with the engineer, Bruce (Tergesen), I said, “Turn on the machine, I want to do something.” So, I got my Gibson guitar, and I played the musical changes to “I Know,” which is a song that was out in ’59 and ’60, by a group from Indiana called The Spaniels–a very legendary r&b group led by Pookie Hudson. I’d always loved that tune. It was written by Luther Dixon, who was a good songwriter, and I said, “Someday I’d like to record that.” That day we weren’t doing anything, so I put down the guitar track, and then I put down seven or eight vocal passes with finger snaps–I just kept singing for a couple hours, and that’s what came out of it. I also did it as a tribute to my oldest friend in the world, Tim Hauser from Manhattan Transfer, and that track is dedicated to him.

MR: Nice Tommy. I caught The Manhattan Transfer at The Blue Note recently, Tim loves you right back. Anyway, the fully-produced version of that ended up being the single, and you played all the addition instruments on it, right?

TW: Yeah, right.

MR: Let’s go back to what you just said. Now, you and Tim Hauser were very close friends in your childhood. How did it begin?

TW: It started in September of ’56, I believe. I was going into my sophomore year of high school, and we were out at recess. I had not even met Tim–he hadn’t gone to the same grammar school–but I heard this guy talking about Frankie Lymon. Frankie Lymon and The Teenagers had just done a show the previous month in Asbury Park’s convention hall that had degenerated into a race riot because black guys were dancing with white girls, and that was a no-no in those days. Tim wound up backstage with The Teenagers–someone had gotten him out of the way so he wouldn’t get hurt–and he saw The Teenagers singing and said, “That’s what I want to do.”

We started to talk, and he said to me that he had a vocal group in Wanamassa, where he lived, and wanted to know if I wanted to be in that. I said, “No, why don’t we start our own group?” When he realized that I could play piano and sing, harmonize, and do arrangements and stuff, he knew he had found a good partner in me. Tim was a guy who really wanted to be in show business and he was a lot more aggressive than I was, so we kind of balanced each other out. We started a group, and we called it The Criterions, which is grammatically incorrect, but halfway decent. We named it after a candy shop in Asbury Park. Then, we started doing practices at my house, and I started teaching him the parts.

We ran into a guy in an elevator in New York named Al Brown, who was an r&b producer from Brooklyn. He produced some demos for us, but we had to pay the band. We went to Bell Sound Studios in New York, and did a song called “Don’t Say Goodbye” that I had written, and a song called “Juanita” that The Crests had done. You can find those two cuts on really obscure compilations of Brooklyn doo-wop albums.

MR: And those singles got airplay and were regional hits, right?

TW: Well, the second version became hits. Tim was the original singer, then we replaced him with a guy named John Mangi, who was more of a trained singer. He became the lead singer, and if you do hear us on the radio, it would be the ones with John singing lead, mostly.

MR: And then, you went to college.

TW: We finished high school together, then we both went to Villanova. By that time music was changing, and The Criterions became a folk group called The Troubadours Three.

MR: Who was the third member?

TW: Jim Ruff, who was also with The Criterions. Jim Ruff went to Penn, and Tim and I went to Villanova, so it was easy for us to get together and sing.

MR: Now, you’re at Villanova and you meet a certain person who you develop a close friendship and a musical career with for a little bit.

TW: The beginning of my junior year, I was assigned to be the student conductor of the glee club, and also audition perspective members. In walked a guy with a big nose and a guitar, and it was Jim Croce. He invited me to his house, I invited him to be in glee club, and we became good friends until he died.

MR: Wow. Now, you had been working with Jim on and off throughout the years, even before his records became hits. You had taken him through several stages including recording him and his wife, Ingrid. Can you give us a quick version of that story into how Jim Croce records became hits?

TW: Well, in the beginning, Jim and I used to sing as a duo. First of all, we were in a twelve folk group at Villanova in ’62 and ’63. Then I graduated, and then he graduated in ’65, and by that time, he had met Ingrid and they became a duo. I brought them to New York and introduced them to my partners Terry Cashman and Gene Pistilli, and they were the first act that we signed when we started our production company, Interrobang Productions and publishing company, Blendingwell Music.

We did an album with him. We were on Capitol Records at the time and we gave it to Nik Venet, who was a legendary producer that had done The Lettermen and some early Beach Boys because we figured he had the juice at the label to get Jim and Ingrid started. So, we gave up the production to him, which was a mistake because the album really wasn’t very good, and it also led to a period of dissension between all of us.

Then, one day, Jim sent me a cassette with “Time In A Bottle” and a couple of other tunes, and he had started to play with Maury Muehleisen on guitar. Maury was brought to us by a guy who was a classmate of mine at Villanova. We signed Maury and did an album with him on Capitol, which didn’t do much, but was critically well received. The thing was, nobody could play guitar like Jim, and Maury helped Jim. I don’t know if he helped write the songs, but he was there as Jim was writing a lot of them, and would shape the chord changes and arrange incredible solos. Terry Cashman and I knew we had something special when Maury joined Jim.

MR: Yeah, they had an incredible guitar sound together that no one to this day can duplicate. The perfect example of that sound would be on “Time In A Bottle.”

TW: I’d never met another human being who could play like Maury did until I found a kid out here named Matt Jaworski, who plays saxophone and a number of different instruments. He’s the only guy I’ve ever seen that could play both of their guitar parts–not at the same time–but he could play what Maury played, and he could play what Jim played.

MR: Wow. What are his other influences, do you know?

TW: He’s a younger guy, but he loves folk music. He loves all that singer-songwriter stuff.

MR: Maury Muehleisen’s album Gingerbreadd has been reissued on CD, right?

TW: Yes.

MR: Okay, let’s go back to your story at the end of college. What was it like going out into the world to make a living in music?

TW: Well, I got a job at a radio station. I had always loved radio, I had done radio shows at Villanova. I got a job a WRLB-FM, which was one of the first stereo FM stations in the country. It really had an eclectic format, which was this: Do the news, put on a Percy Faith album, and let it play. Then, when side one ends, don’t worry about dead air, just gently flip it over and play side b. Do the news again, do a bunch of commercials, and put on another Percy Faith record. It was that kind of format, which was death. But it had a great signal and a great sound. I’d be playing classical music at night, and I’d get all these calls, so I asked the owners if I could do a morning show as a disc jockey. So, I became the morning man at WRLB for awhile, but I realized it was going nowhere.

So, I moved to New York and got a job at ABC Records as a promotion man, which I was terrible at–if there was a cloud in the sky I wouldn’t go to work. But I wound up going to demo sessions because on the same floor as my division of ABC was the publishing division where Terry Cashman was the manager, and he had signed Gene Pistilli. I realized that Cashman was the same guy that had sung with a group called The Chevrons, who were out when The Criterions were out. So, they invited me to go to demo sessions, I ended up singing with them, and we became a trio. One night, while I was singing a demo for Cashman, a kid named Kenny Karen, who was a jingle singer, was looking for another jingle singer to do a jingle for White Rock soda to the tune of “Hey There, Georgie Girl.” He heard me sing, and he invited me to be on the demo commercial. The next day I quit my job and became a studio singer.

MR: So, you’re on that classic jingle, “Hey there, White Rock Girl.”

TW: Yeah.

MR: As a jingle singer, you’re also on “I’d Like To Teach The World To Sing,” that famous Coke commercial, and as a background singer, you’re on Frank Sinatra’s “The World We Knew.” Okay, then you begin the next phase of your recording career as Cashman, Pistilli and West.

TW: Yeah, we started that in ’68.

MR: So, when Terry Cashman–or Dennis Minogue, as he was known at the time–oversaw the publishing company, what was his job like?

TW: Well, his job was to find songs to get to producers, he signed a number of different writers that he had found. He was a great publishing guy–Dennis had great ears, and he knew a hit when he heard it. He and Gene had written a song called “Sunday Will Never Be The Same,” which they had originally written as a follow up to “Walk Away Renee” for The Left Banke, but they didn’t want it. Then, Jerry Ross heard it and cut it with Spanky & Our Gang, and it was a big, hit record.

MR: What were you, Cashman and Pistilli doing together at that time?

TW: We did the studio group thing. We wrote a song called “One Wonderful Moment,” and we called ourselves The Shakers. Then, we wrote another song about Twiggy, the British model, and we called ourselves The Magpies. It was just silly stuff, but it gave us an opportunity to get into the studio and learn how to produce records, which was a great experience.

MR: And then comes the first official Cashman, Pistilli and West album, Bound To Happen.

TW: Right. Then, we left ABC and went to Capitol where we did what we call our “White Album,” Cashman, Pistilli & West. It was on that album that we did my favorite song that we recorded, “Some Of My Best Friends Are People.”

MR: Jeez, there’s so much more to talk to about in that period, like your hits as The Buchanan Brothers that included “Medicine Man” and all your other recording monikers like Central Park West and CPW. What happened between the point when Gene left and you became Cashman & West?

TW: After we did the Bound To Happen record, we realized that nothing was going to happen at ABC, and Cashman wanted to leave there. Somehow, our stuff had gotten to Nik Venet, who had moved from California to New York to run the A&R division at Capitol Records. He heard what we did and he really liked it, so he brought us into the studio and we started doing our “White Album.” During that time, we were working with John Stockfish, who had played with Gordon Lightfoot, and Croce used to play back-up guitar on some of those tracks. The album got tremendous critical acclaim, and it did okay–it sold a little bit. Nik had a habit of leaving the studio before the group was finished with the project, so we wound up mixing things ourselves, and again, it gave us more time in the studio.

Then, we decided to write a follow-up album that was never released called Out Of Time, which was deep concept album about war babies, baby boomers, and all that stuff. At the same time, Gene wanted to go off on his own, and he wound up in the initial lineup of The Manhattan Transfer with Tim Hauser and my ex-wife, Pat. Gene went on his own, and Cashman and I decided to stay together and became Cashman & West. We also did studio group things for Capitol. We recorded as Laredo on a song called “She Never Looked Better.” We were trying to find that elusive major hit, which we never really had, but we did well enough that people know who we are today.

MR: Would “California On My Mind” be considered the first Cashman & West single?

TW: In a way, I guess it could be. We were into jingles, and somehow, we got an assignment to write a song for Kodak. “Kodak makes your pictures count” was the tag line, and that line was given by the ad agency, which I think was J. Walter Thompson, to four or five different production companies and writing teams. So, “California On My Mind” wasn’t even conceived then–it was just “Kodak makes your pictures count.” Well, they used our track as their jingle for a while, and we decided, for whatever reason, to write a song to that track, and that became “California On My Mind.” We put it on a little label called Vent, which was a little indie, mostly black label, and we knew the owners, so they put it out and it made the charts. The funny thing was, you could listen to a radio station, and the disc jockey would play “California On My Mind,” and then he’d play the Kodak commercial, and it was the exact same music track, just with a different voice.

MR: You had some other commercial staples, like the one for Total, right?

TW: (singing) “Today is the first day of the rest of your life. Start it right with Total.”

MR: (laughs) Nice, thank you, Tommy!

TW: That was on the CBS Network News with Walter Cronkite for a long time.

MR: Right, that’s right. You also had a Remington commercial?

TW: (singing) “Remington’s electric shaver, why not do your face a favor?” We got sued by Bobby Russell, who wrote “Little Green Apples.” He thought we stole it.

MR: What was the outcome?

TW: Nothing happened.

MR: We talked about “Sunday Will Never Be The Same” by Cashman and Pistilli, but there are songs your wrote with Terry Cashman that were covered by other acts that did very well.

TW: Well, off the Bound To Happen album, there was a song called, “But For Love” that was cut by seven people.

MR: Right.

TW: Eddie Arnold cut it, The Mills Brothers–my favorite vocal group of all time–cut it, a guy by they name of Jerry Naylor did it twice as a country record. Then, off the “white” album, “Sausalito,” which was going to be our first single, got pulled from us and given to Al Martino, who had a major MOR hit with it. Cass Elliot did “A Song That Never Comes” offBound To Happen.

MR: There you go. I remember when I was working for you and Dennis (Terry Cashman) at Blendingwell Music, you had all those singles on the cork wall in the music room. It seemed like there was one being added every week. That was a beautiful period.

TW: Yes it was.

MR: Let’s talk about The Partridge Family, but to get into The Partridge Family, you have to talk about your recording of “Child Of Mine.”

TW: In the last part of Cashman, Pistilli & West being on Capitol, I heard a song called “Child Of Mine,” which I really loved, by Carole King. Wes Farrell produced a version of that with us. Capitol had brought him in to try and get a hit single with us. The first single was called “Goodbye Joe,” which didn’t do too well, then I wanted to do “Child Of Mine,” so we did sort of a country pop version of that.

MR: Now, there was a song in that same period that went unreleased, right?

TW: Wes cut a track on “Candida” with us, and then he must have cut the track that he used with Tony Orlando because all of a sudden, he lost interest in our track.

MR: So, Wes Farrell then produces The Partridge Family…

TW: …yeah, Wes had done a bunch of bubblegum records, and he told us one day that he was going to do this TV project called, The Partridge Family. He invited Cashman and me, and a bunch of writers to watch the pilot to the show, and he said, “I want all you people to start giving me songs.” We wrote “Only A Moment Ago” and “She’d Rather Have The Rain,” which were the first two songs accepted.

MR: Now, “She’d Rather Have The Rain” was on The Partridge Family’s Up To Date album, and I think it’s one of the only Partridge Family songs where you can actually hear Shirley Jones singing a little on there.

TW: Uh huh.

MR: And there were six other Partridge Family favorites like “Come On Love,” “It’s Time That I New You Better,” and “Sunshine Eyes” that you guys penned. You also had the Cashman & West song “Follow The Man With The Music” from your album Moondog Serenade covered by a well-known group, right?

TW: Yeah, a country/gospel group, The Imperials.

MR: Alright, I’m getting ahead here. Cashman & West sign with the label ABC-Dunhill, and that’s how Jim Croce got his recording contract.

TW: We had been trying to place the finished You Don’t Mess Around With Jim album with a label for months, and nothing would happen. We basically made a deal with ABC to just put out a single and we’d leave them alone. Marty Kupps, the promotion man, got “You Don’t Mess Around With Jim” on KHJ, and the rest was history.

MR: That’s funny that nobody wanted it, and then it became one of the biggest albums ever.

TW: Yep.

MR: And Cashman & West had their own hit on Dunhill.

TW: Well, our first single off the A Song Or Two album was “American City Suite.” That was noteworthy in the fact that it was so long.

MR: (laughs) Okay, and it was compared to Simon & Garfunkel material, it predating “My Little Town” by like four or five years.

TW: We had done most of the album and we were looking for something special. That was when the Hari Krishna people were going through Manhattan on their wagon, and a lot of bad stuff was happening in the city. So, we put together a medley, which I call a suite of songs, like a classically arranged suite of songs, and that’s what made it different. There is a section in the third song, “Goodbye is too hard for me to say,” just before “All Around The Town” starts–I think that was the best vocal sound that we ever had as a duo.

MR: Yeah, “American City Suite” is beautiful, it’s got to be nice to have as part of your legacy. And I believe “A Friend Is Dying” being the climax of that piece, tempted stations in a lot of markets to highlight just that segment.

TW: Yep.

MR: Tommy, Cashman & West had three albums on ABC-Dunhill–A Song Or Two,Moondog Serenade, and Lifesong. Simultaneously, you two produced albums and singles by Jim Croce, Mary Travers, Dion DiMucci, Eric Anderson, Henry Gross, Jim Dawson, Adam Miller, and William St. James. Then there was a certain point where you wanted to start a label. Can you go into why?

TW: Like all people who all of a sudden become successful, we figured that if we had our own label, then we wouldn’t have to schlep up the streets of New York trying to sell people what we were doing. I don’t know if it was a good idea or a bad idea, but we did it, and we called it Lifesong, after the album, Lifesong. We tried to find the finest singer-songwriters because that’s what we were, and it was easy finding the artists because we were successful–everybody who played guitar came through our offices at one time or another.

MR: Yeah, I remember James Taylor pitching Livingston when he dropped by to buy LSR guitar strings–your business venture will Phil Petillo–and Aztec Two-Step as well.

TW: So, we went in that direction. We signed Henry Gross, we signed an extremely talented (artist) by the name of Dean Friedman, and a band called Crack The Sky that I still think is one of the greatest bands ever formed.

MR: Absolutely.

TW: We had some success–Henry Gross’ single, “Shannon” sold a million and a half copies in ’76, one of only a handful of songs that went platinum that year. Dean Friedman’s “Ariel” stayed on the charts for a number of months. Crack The Sky got great critical acclaim.

MR: Including Rolling Stone‘s ’76 Debut Album of the Year, I think.

TW: Really?

MR: Yeah. I remember Lifesong’s musical genres being very diverse and eclectic, ranging from the fabulous comeback album by Dion DiMucci, The Return Of The Wanderer, to a Spider-Man album. Then came Gail Davies, your first real country act.

TW: I started going down to Nashville. I had met Ed Bruce when I did his song, “Mammas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys,” and all of a sudden, somebody brought in Gail Davies to listen to. I knew she was extraordinarily talented, so we signed her. We had a label deal with Epic at the time, so our country stuff was distributed through Epic in Nashville. So, by the end of the ’70s, I was producing everything I did in Nashville–I became Tommy West, country producer for ten years.

MR: Where you also produced a number of Top Ten hits and albums for Ed Bruce on MCA. From there, you started up the MTM label for Mary Tyler Moore’s company in Nashville. Basically, it was built around all your acts and productions.

TW: Well, they had a label all ready to go, because I had about twenty-eight masters produced in the time before MTM that had not been released.

MR: Who were some of the acts on that label?

TW: The Girls Next Door, Judy Rodman, Holly Dunn, and The Almost Brothers.

MR: That was a really great period where, literally, everything you produced charted. It was a very good run for a label like that, coming out of nowhere and just showing up in Nashville.

TW: Well, I wanted it to be kind of a country Motown, which it was for a while, and then politics hit it and the rest is history.

MR: After that, you hooked up with Anne Murray. You were obsessed with her records from her first single. What’s that story?

TW: It was ’70, I was on my way to do The Mike Douglas Show as Cashman, Pistilli And West, and I heard a song on the radio that I’d heard once before, but I didn’t know who the singer was. We’d had a little fender bender at a red light, and as we were pulling off the road, I said, “Leave the radio on,” and the guy on the radio said, “That was ‘Snowbird’ by Anne Murray.” It was like God came to me and said, “You’ve got to get this voice.” It was like love at first listen. So, I wrote to Capitol in Canada because I’d found out that she was on Capitol like we were, and she sent me a copy of the album, which I wore out. I still listen to it with earphones and sing along. I’d never heard a human voice that was better than that, and it only took me twenty years to get her in the studio. But once I did, it was a match made in heaven.

MR: It certainly was, you had many gold and platinum records producing her withCroonin’ being an instant classic.

TW: Yep.

MR: And I would say you basically revived her career, and in her book, she says some really amazing things about you.

TW: She really was very complimentary, and Anne is very conservative with her praise. Her applauding me is like a four star review. In all the projects I did with her, I never heard her complain about how hard it was to get something, and I never heard her sing out of tune, ever–even when she wasn’t feeling well. She was just one of those forces of nature. People really don’t give her the respect she deserves because people thought she didn’t sing fancy enough sometimes. But I can put stuff on that I did with her back in ’93 and it sounds as fresh as the day we recorded it.

MR: And I imagine there are great memories of her in the studio too.

TW: Oh, it was wonderful.

MR: You also produced a guy named Bob Hillman, right?

TW: Yep, you brought Bob Hillman to my attention. I remember playing the demo you had given me, riding with my wife. I said, “What do you think?” And she said, “I think you’ve got to record this guy.” So, we did two albums, which I played recently, and they sound better now than they did then.

MR: (laughs) You’ve been accused in the past of always being ahead of the curve.

TW: Either that or so far behind it that I’m ahead.

MR: (laughs) Tommy, I think Bob Hillman is one of those artists that was a joy for us to watch grow. God, he’s such an incredible songwriter, such a well-rounded human, and your productions with him were a perfect match. But then, you’ve always been great with new artists in and out of the studio, one of your qualities that I’ve tried to emulate over the years. So, with all your experience working with them–and there’s almost no one who’s more qualified to answer this question–what kind of advice would you give to a new artist these days?

TW: That’s really tough. Well, if you’re serious about being in the business, learn to take rejection, and don’t let it stop you because nobody really knows anything in this business–it’s a business of feel and intuition that is later backed up with marketing. Now, because of the internet, anybody can be a record label. I hear names of groups that I’ve never heard of getting a million hits instead of selling a million copies, which is just as good. The good part is that you can sort of support yourself if you know how to have a decent website and play live. But to sell tonnage, you still need a major distribution network. When I started it was really hard too, though it always looks simpler in hindsight. In those days, you made a record, did a demo of it, scraped up enough money to do it, you knew an uncle who knew somebody he was in Pearl Harbor with that went into music, and you got lucky. Then, you wound up like Elvis did–somebody who was so different that he couldn’t be denied. That happens. These forces of nature come along every now and then that can’t be denied.

MR: You’ve had so many different roles in the music industry over the years–what did you like doing best?

TW: Overdubbing my voice…singing harmony, either with myself or somebody else.

MR: You also had a period where you did…you called the project “Nuwop,” right?

TW: Yes.

MR: That was a bunch of songs that you had recorded as another solo project and those are also on the reissue of Hometown Frolics.

TW: I love those things.

MR: What is the story behind those tracks?

TW: Well, I had bought a lot of sound equipment to put in my barn and I was trying to figure out how to use it. So, I picked up a microphone, sat behind the control board and started singing–it was a song I’d always loved called, “Babalu’s Wedding Day.” I just kept singing and singing, and it took me a week to get through about thirty passes of “Babalu’s Wedding Day.” I said, “Boy, this really sounds good.” Then, there was another song called, “Girl Of My Dreams.” I knew I would never do anything with it, but I have the tracks to “In The Still Of The Night” and a bunch of other things. They’re like synthesizer tracks with vocal backgrounds that I just never put the leads on. I don’t know what I’m waiting for.

MR: Yeah, what are you waiting for? I want that album. (laughs)

TW: Maybe when I’m on my deathbed, I’ll do the vocals and it will be more effective.

MR: Oh my. Hey, there was a song in that batch by Tony Romeo, right?

TW: Yeah, “On The Night We Met.”

MR: All three of those Nuwop tracks are just beautiful.

TW: I also recorded that song with my daughter Cheyenne and two other girls.

MR: And all three of those appear on the double disc reissue of Hometown Frolics andTerry Cashman. Tommy, this has been incredible. I really appreciate your time and stories.

TW: You know what I wish you’d do?

MR: Anything, what?

TW: As a closing song, would you play “The Dreamer” by Cashman? (Note: This interview was broadcast on solar-powered KRUU-FM)

MR: Yeah. Do you want to go into the story of that?

TW: I don’t know if there’s a story to it.

MR: (laughs) Well, that was one of the songs that you guys had when you were starting your fourth album, before it became two albums, right?

TW: I think so. When I listen to that song, I get very nostalgic because I knew that Cashman And West wouldn’t be singing much anymore. There is something about the vocal blend on that that is just fabulous.

MR: It is. Tommy, thanks again for the time. Out of all the people that I’ve interviewed, this is probably the most important interview for me because of our connection and the fact that you really started me in the music business. I just want to thank you. I’m almost getting teary here.

TW: That’s okay. Make sure you play this on a sunny day, when you get a lot of power. I stupidly think that on a cloudy day the station isn’t as powerful as on a sunny day.

MR: (laughs) Maybe it’s not. What I want to know is, why isn’t everybody using solar power? It’s here, it’s cheap, it’s free.

TW: That’s the reason–nobody can make money off it.

MR: That’s a shame. Anyway, let’s close with “The Dreamer.” Thanks Tommy for everything.

TW: Thank you, Michael.

photo credit: Mike Ragogna

HAPPY BIRTHDAY TOMMY!

Patiently Transcribed by Ryan Gaffney