A Conversation with The Flaming Lips’ Wayne Coyne – HuffPost 4.15.11

Mike Ragogna: Hey, it’s Wayne Coyne — master genius, lead vocalist, and experimenteurof The Flaming Lips.

Wayne Coyne: Well, thank you Mike, now I don’t know what to say. I thought we’d (talk about) “She Don’t Use Jelly,” and you’d say, “Wayne, why’d you write such a silly song?” Now, I feel obligated to love you for all of that.

MR: Wayne, why’d you write such a silly song?

WC: (laughs) You know, if you’re lucky, you don’t know what you’re going to write. If you’re lucky, something comes out that has this element of you in it. Sometimes, people think, “Wayne, that’s such a quirky song,” but I don’t think it is. To me, if you were around me, you would think, “Oh yeah, you guys are sort of like that.” I think that that song — probably because I’ve said it — people have taken it as meaning sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. When people say, “She Don’t Use Jelly,” they always think I’m referring to some kind of sex jelly or something, you know? But I wasn’t! When I was writing this song, it was simply about, instead of putting butter and jelly on toast, we were talking about putting Vaseline on toast, tricking someone. Sometimes, we would think that the butter we were using was basically just grease anyway. So, it was based on this silly, but realistic version of what was happening in our lives.

MR: You’re just a bunch of Heady Nuggs, aren’t you.

WC: (laughs) See, that term “Heady Nuggs,” that’s not my term. That’s a term that someone alighted me to. I thought it sounded cool, but everybody said, “You know, Wayne, everybody has been saying that for years.” I thought it was kind of something the guys I was around made up, but isn’t that a great term?

MR: Yeah, it’s both heady and nuggy. Alright, let’s get to those vinyl Heady Nuggs, which is your first few albums for Warner Bros. packaged together in a nice set, basically ranging from ’92 to ’02, oui?

WC: Well, we don’t really have a logic to it. There is one record that is not in there, and some of these were records were slightly released, going back to our first release on Warner Bros. in ’92 but wasn’t released in America. So, it’s a collection of vinyl, but it’s not every record that we’ve done. Part of the reason, and I’m not sure why it was collected this way, but we decided this makes perfect sense for The Flaming Lips. It wouldn’t make sense for every group, but it makes sense for us. So, it’s a collection of not even our first five records because I think there’s one record that’s not in there. You have to remember, it’s a long time ago that we started to make this record that came out in ’92, but since we do most of it ourselves, and we’ve had this long relationship with Warner Bros., a lot of this repackaging is still kind of available to us. So, we had to redo, or remix the music, and repackage, which meant finding all these photographs, and all these things that built the initial twelve inch, vinyl record that you could buy way back in the day in ’92. Luckily, I still have all of that. There was a toilet — for the people who don’t know this record, Hit To Death In The Future Head — which was only issued in Germany, the cover is this toilet that kind of has this psychedelic toilet seat on it.

MR: I owned it, sir. The album, not the toilet seat.

WC: Well, that’s the photograph that’s on the cover. As a testimony to how stable and resilient my life is, that toilet is still being used upstairs in my house.

MR: (laughs) Wow, that’s really wonderful.

WC: This isn’t just some photo a some crazy toilet, somewhere in the world, it’s actually still in my house, so we just took another picture of it and said, “Here it is now.” I’m amazed at how well a toilet seat can hold up.

MR: Truly resilient, yes. (laughs) Hey, you’re one of the kings of experimentation, and you’re one of my personal heroes in that regard.

WC: Thank you, thank you. To me, anytime someone is doing art, music, or any of these things that involve trying something new, if they’re not willing to experiment, they’re not going to get anywhere. It’s this idea that you’re always trying things, wanting to try things, and not worried about things failing. To me, this is how we should live our lives anyway. We have to try new things and see what happens. With music and art, that’s that only thing we have. I never wanted to make art or music just to do the same thing every day. I want to do new things, try things, go new places, meet new people, and do weird things that I’ve never done before. So, to me, that will always be part of it.

MR: We’ve made music generic, and put it into little safe places for so long–you’ve got pop, you’ve got rock, you’ve got this, you’ve got that. But I feel that output from people like you should be more referred to as “expressionism” because it encompasses so many realms. For instance, Zaireeka, your four-CD set that was meant to be played simultaneously.

WC: Yeah, exactly.

MR: See, that’s different, not easy to categorize. Also, when you did the “The Parking Lot Experiments” and “The Boom Box Experiments”…

WC: … but a lot of people would say, “Isn’t this absurd? Isn’t music already wonderful the way that it is?” To them, I would say, “It is, and if that’s the way you look at the world, that’s fine.” I’m not trying to change anybody’s world. To me, it’s just curiosity of my own world, for my own entertainment, really. Like you’re speaking of, I think there are a lot of people out there thinking the same thing I do, saying, “Oh, this is wonderful that this doesn’t have to fall into a category. We don’t really have to know what it is, it’s music, we don’t really need it to be in a category.” A lot of people, I suppose, want things to be in a category, they want to know what’s going to happen before they get there. It’s kind of like watching a trailer to a movie, “Hey, I kind of want to know what I’m getting before I get in there,” and that would be true, but if you know The Flaming Lips or understand us, you kind of already know what you’re going to get. But it’s hopefully going to be full of surprises.

MR: I always looked forward to each album. I loved Embryonic, but bizarrely, The Flaming Lips and Stardeath and White Dwarfs with Henry Rollins and Peaches Doing The Dark Side of the Moon…

WC: …that’s our little dog walking in the background.

MR: (laughs) See what I mean? You can’t help yourself. I bet you’re recording this interview and it will be part of some experiment.

WC: I could be. I’m actually speaking in a room that has a lot of microphones, but it would mostly just sound like me talking, and we have a lot of that, you know?

MR: (laughs) Alright, The Flaming Lips and Stardeath and White Dwarfs with Henry Rollins and Peaches Doing The Dark Side of the Moon, well, you listen to it, and that title actually makes perfect sense.

WC: Well, even the idea of having someone like Henry Rollins be involved with a Pink Floyd album. I’ve known Henry since about ’83, when I saw him play with Black Flag way back in the day. But of all the humans that love music as intensely as he does, of all the humans in the world, he is the one guy that I know had never listened to Pink Floyd’s Dark Side Of The Moon. So, he was the exact guy that I wanted to call because that’s exactly what we were doing — we were just injecting another version of what has now become universal music, what it could be. Some of the music that Pink Floyd has done is like part of our DNA, it’s part of what music is to people, not because of Pink Floyd, but because it’s universal — sort of simple, powerful sounds. So, Henry, being this voice — the voices on the original Dark Side Of The Moon are just strange, kind of whimsical, English guys, and Henry is not whimsical. Henry is intense, and he’s like a motivational speaker. So, to hear him talk about things like wondering about suicide and violence, to me, gave it even more power, and put a new twist on it.

MR: This is what I’m talking about. What you did is, you took someone as wonderful and intense and knowledgeable as Henry Rollins, and you used him as an element of Dark Side Of The Moon because he’d never heard it before. It’s intellectual and proactive.

WC: Well, I’m very lucky that people are trusting enough, and are willing to take a chance with me. Someone like Henry could easily say, “Wayne, I don’t really like that music,” but I think he trusts that we’ll use him and abuse him in a great way. That being said, I’m very lucky that people are willing to take a chance.

MR: Wayne, you’re also associated with a college out in Oklahoma City, aren’t you?

WC: Well, it’s a new sort of music school called, The Academy of Contemporary Music. Our manager, he’s the CEO of it, and I don’t think the school would have existed or had the inertia to come into existence without him. He does all the work and I get all the credit because I’m in a band and people love the music that we make. Depending on what city you’re sitting in, you could say, “That’s not that big of a deal.” But I would say, for Oklahoma City to have something like this, where kids — and it’s not for everybody, you have to have the grades and do the work — where kids can meet people like them, who are into production, playing instruments, and people who are into singing and writing songs is changing everything here. It’s changing things so people don’t feel like, “I’m a musician, but why do I want to live in Oklahoma City? Why don’t I move to LA or New York or somewhere where there is a music scene.” For some people, that’s never going to be possible because they can’t leave, this is their home, and they don’t have a choice. In fact, a lot of people think that’s what happened to me, but that’s not what really happened to me. I never thought that I was trapped in Oklahoma, I just thought you could make music, and it didn’t matter where you were. But that’s not as true for everybody as it was for me. I was lucky. So, this school acts as a sense of saying, “Yes, make your music, live your life, and become the thing you want to do.” It also lets you meet other people who are thinking the same way you do, which might otherwise be impossible in a place like Oklahoma City.

MR: It’s associated with The University of Central Oklahoma, right?

WC: That’s right.

MR: That’s cool, not only that it’s accredited, but also, it seems to be continuing a trend where music departments are giving more credibility to teaching more contemporary applications of music. In the past, it would be more conservatory based, but now it seems that they’re getting the point that the kids want to go to — speaking loosely — schools of rock, you know?

WC: It’s exactly that, but I don’t think they have to be bad. I think any kind of exposure that people get to people who are interested in the same thing is going to push them along. You might have people helping you with an idea that you think is important now, but the more you learn about it, you might think, “Wow, there’s so much out there.” Any exposure, any time you’re hearing new ideas and new music, anytime you’re around people who are intense about what they believe in, that’s good. The worst thing in the world is to just sit at home, watch TV, and think, “Oh, it’s all been done, what’s the point?” Once you get out there in the world, you meet people that give you ideas, give you energies, give you reasons to live…yeah.

MR: What people in your life inspired you?

WC: Well, I’m fifty years old, so I’ve been around for a long time. Even in the very early part of my life, I never had to go very far before there was music around, and there were weirdo artists around. I grew up in a family where I have older brothers and an older sister who, for better or worse, loved music, loved to take drugs, and loved to do crazy things all the time. So, I’ve been in this environment, I guess, my whole life, where there is the desire to be doing something with some intensity. For me, growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, I can’t remember a world where there wasn’t something fantastic like The Beatles, or a Led Zeppelin, or a Pink Floyd. I even saw Led Zeppelin and The Who in their heyday, in the ’70s. My brothers took me to see those bands when I was fourteen years old. Even meeting someone like Henry Rollins — when Henry and Black Flag played in Oklahoma City, they only played to about fifty people, this wasn’t a stadium full of adoring fans. I saw that these were people just like me, trying to do their music their way. They were doing it — they weren’t just sitting around, dreaming — they were actually living this life that they wanted to exist for them.

It’s never really been just famous people who have inspired me, so much as people that have been around me. My brothers themselves, to me, were great inspirations because they could draw, and they could fight, and they would do things. They were not afraid, and luckily, I think some of that has rubbed off on me. Luckily, too, I don’t do as many drugs or get in as many fights as they did — a lot of my fight went into being in a rock band, making music, and stuff like that. I can’t underestimate how much being around them and their lives had to do with what I wanted to sing about and what I wanted to be.

MR: Can you talk a little about the formation of the band, just for the ten people who don’t know?

WC: You couldn’t have grown up when I did, and not have thought that being in a rock group was great. This isn’t to downplay the music, but to us, it wasn’t really about the music. It was about being in a rock group because being in a rock group lets you play loud music, do intense things. You got to be around a bunch of weird people, you got to see the world, and it hinted at another life. We never thought, and I still don’t, that we were these great musicians that the world needed to hear. We simply formed this group because we wanted to live that life. Early on, we didn’t know what we were going to do, but we ran into groups from around town, and groups that were coming through town, that were playing this Americanized version of puck rock. These were groups like The Minutemen, Husker Du, Black Flag, and even some local groups here. There were some really great, local weirdos that very much inspired us. So, we though we would just form a group — we didn’t know what we were going to call it, and we didn’t really know what kind of music we were going to play because we couldn’t play very well. As a result of that, we couldn’t play anybody else’s music — we couldn’t just go out there and play Beatles songs, or Led Zeppelin songs, or Sex Pistol songs, or whoever it was that we were admiring because we didn’t know how. So, we just kind of made up our own songs, and I think that’s the thing, in the end, that changed everything. We just thought, “Well, we’ll just be a band that does our music.”

We still run into people that were around us at that time, and they would say, “It’s so weird that you guys are making your own music.” These guys that we were around were in cover bands, playing Lynyrd Skynard, The Police, and groups that they admired. They said, “You guys just started to play your own music, and everybody thought, ‘Wow, how weird, and how brave.’ But they also thought, ‘How stupid.'” We knew so little about how things worked that I think it gave us a great power because we weren’t that afraid. We really thought, “If nobody likes us, we’re not that good, and it wouldn’t bother us very much.” I think the people that did like us saw something about our spirit and about our authenticity and about what we believed in that they liked. So, we were lucky about that thing about us, that I don’t think we have any control over or know how to control, has an effect on some people. I wouldn’t say it affects everybody, but it has a powerful effect on some people.

MR: True, but you and groups like Sonic Youth are the prototypes for indie bands. What advice do you have for new artists?

WC: Well, I would say, you cannot wait, and you cannot be lazy, and you cannot be afraid that you’re not going to be a big rock star — you kind of just have to pursue all these things. The things we’re doing now are very much like the things we were doing when we started. When we started, we made our own record — I sent it out to a record plant to have it made, and I made my own album cover on my kitchen table; and now we’ve been on Warner Bros. for twenty years, and we’re now working with Warner Bros. almost as an independent label, but we’re not. This is the way that us and Warner Bros. want to work because they want us to try new ways of doing things. We’re doing these things now, where we’re making our own records — there is a record plant three hours away from me, where I literally go myself and make the vinyl. I put the vinyl into the machine and it comes out the other side pressed into a record. I’m working with a pressing plant here that makes album covers, and I have a guy that is in my house working on computer graphics, video, web design, and all that. We do it all, really, ourselves, and we want to. We want to make our art be… like you keep saying, “It is an expression of who we are.” That comes down to making these giant, life-sized gummy-skulls that are going to have a USB drive in them. That will be a vehicle where you can have this thing that carries our music in it. It’s an object that we made, it’s an object that you can have, and it’s an object that you can even eat.

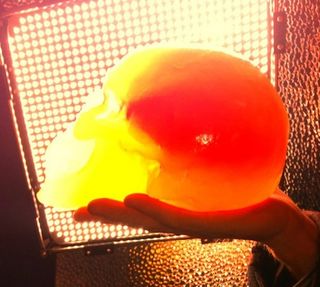

MR: I was seconds from bringing that up. Do you call it the Gummskull?

WC: Well, the Gummy-skull. If I call it a gummy bear skull, they think it’s going to be a bear skull, and I’m like, “No, it’s made out of Gummy Bear candy, but it’s a life-sized, human skull that has a life-sized brain inside of it as well, and inside this gummy-brain is a USB flash drive that has four new Flaming Lips songs on it. This is just another version of how people can deliver music to their audience. I wouldn’t say that every band would be able to do this — it’s hard even for a band that has as many connections as we do. But it obviously can be done. I don’t know if the audience will like it, but I think that the audience should love it… in a way, I know I love it. It’s absurd, it’s unexpected, and I think it’s wonderful.

We had this concept, even with our first EP that came out in ’84 — it had this skull on the cover. For whatever reason, we thought this was a resurgence or a revisiting of this independent way that we had. So, we started thinking about this skull as our mascot. At first, we were trying to make it out of bubblegum, but we couldn’t find any bubblegum manufacturers who would do it. Then, we stumbled onto this guy in Raleigh, North Carolina, who was already making giant gummy-things, so we sent him a mold of our skull, and he said, “Wow, I’m a Flaming Lips fan already, let me help you.” In some ways, you have to hope with some serendipity that you run into people who will help you, and we’ve been lucky that that’s happened.

MR: Yeah, I’m dying to see, on YouTube, somebody eating their way through that gummy-brain to get to the USB.

WC: Well, I have a video of one of our roadies, who has great, sharp teeth, biting into this because we had to know if it would work. Frankly, we didn’t want to put it out there if it wasn’t going to work, but mostly, we wanted to see if the USB drive got damaged in any of this cooking that you have to do to make this gummy candy. So, we have a video of him eating into the skull, then the brain, retrieving the USB drive, and lo and behold, it plays perfectly. So, I feel confident that it’s all going to work. There will probably be some weirdoes here or there that are going to complain about a stomachache. But other than that, I think it’s going to be wonderful.

MR: Well, there’s going to be a children’s warning on there, right?

WC: Do you really need a warning? I think it should say, “Look, this is a big piece of candy. Eat it with about twenty of your friends, otherwise, nibble at it here and there.” Everybody already knows that, right?

MR: Let’s talk about all the touring you’ve got going to support all this stuff.

WC: Well, in a sense, we never really tour — we’re just always out playing. I think if you were to speak with a group like Pearl Jam, they would play two-hundred shows in a year, and then, you wouldn’t see them for a couple of years. And in a lot of ways, I think that’s a great way for most groups to do it, but it doesn’t really work like that for us. We kind of are always playing, but we don’t play that many shows — maybe 50 or 60 show per year — but we do it almost every year. We try, every year, to play quite a few new places that we’ve never played somewhere out in the world. I’m leaving for Chile and Argentina, and I’ve never been there, so, for me, it’s already a great adventure to say, “Look, I get to go visit Easter Island and I get to play Flaming Lips music in Buenos Aires.” To me, that’s already wonderful. And, in a sense, we get to play all around America, Europe and Asia, sometimes at giant, established festivals, and sometimes at strange little festivals that are in the mountains out in North Carolina somewhere.

It’s not always just to Flaming Lips fans, either. Sometimes, we’re playing festivals that are attached to bigger things–like the thing we’re doing over the weekend is a Lollapalooza, where Lady Gaga is headlining the day that we’re playing. So, there’s always a big variety in the audience that we’re playing to, but we’re also often playing to the hardcore Flaming Lips audience somewhere out there. It never feels, though, like we’re promoting something–we’re there to play for that audience. We’re never saying, “Hey, this is about this record we have.” It’s always about the experience that we’re going to have with the audience. Obviously, we’ll play a couple of new songs here and there, but it mostly is something about this life of being in The Flaming Lips. We get to have this night together wherever it is in the world that night when we’re playing this music. Without the love and energy of the audience, it is just people playing music. But with the love, energy, and life that the audience gives it, it can be an epic experience, not just for the audience, but for us, playing.

MR: And you’re still going to be performing The Soft Bulletin, I hope.

WC: We’re doing some shows throughout the summer where we just play The Soft Bulletin, and other shows where we just play The Dark Side Of The Moon… So, there are opportunities to see these exclusive shows, where you’ll know, in a sense, exactly what we’re going to play. A lot of the shows that we’re playing will be a combination of everything that we deem to be our greatest hits or our great live performance songs that we do. But some of them are, like you said, these moments that are only from The Soft Bulletin record or The Dark Side Of The Moon… record.

MR: Wayne, I wish we had a million years to talk, but I’ll let you go. You’re one of my heroes, and I’m so glad that I got to interview you. Any last thought?

WC: Well, thank you for saying that. A lot of times I’m speaking with people that know a lot about music, a lot about art, and a lot about this thing that you speak of — expressionism. When you said that earlier, I thought, “What a great thing to say.” Thank you for having me on your show, and I hope your show goes on for a million years, and we’ll speak again.

Transcribed by Ryan Gaffney