June 18, 2014

Chats with Peter Frampton, Chicago’s Robert Lamm, The Doobie Brothers’ Tom Johnston and the Legendary Buzz Cason

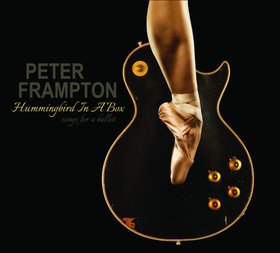

A Conversation with Peter Frampton

Mike Ragogna: Peter, the last time we spoke, you mentioned you were about to score a ballet and now you've released Hummingbird In A Box, its companion album. What have the adventures been leading up to the ballet and this particular project?

Peter Frampton: It all started a few years ago when the Cincinnati Ballet asked if they could do choreography to four of my songs; three instrumentals from Fingerprints and then "Not Forgotten" from the Now album. I said yes, but then I got incredibly busy, was out-of-town, and never got a chance to see it. They sent me a DVD, so I finally did get to see it, and I was blown away with the choreography and dancing. Then Victoria Morgan and I got together at the headquarters to watch a rehearsal for a new performance they were going to be doing--I think it was Carmen at the time--and she asked if I would perform live on stage with my band, saying, "We've done this once before; we had a band onstage and we choreographed to their live music." I said, "Yes, I'd love to do that." There are three segments in the ballet, about 20-to-25-minutes each. I asked her, "So I let you know what music I do live and you choose the choreography?" She said yes, and I ended up writing the music for the middle 28 minutes, seven different pieces. They were floored that I would want to do that, but I did it. We performed with them in April of last year; three shows in Cincinnati at the Aronoff Center. We were on stage, Adam Hoagland was the choreographer, and the whole thing was just phenomenal. Then I went on tour with the Guitar Circus, and after finishing, they used the music for the Cincinnati Ballet at The Joyce Theater, a performance last week in New York. So when I got off the tour, I went into the studio and finished the tracks that we'd played live, and we heard the finished music playing live in Manhattan. Gordon Kennedy--who wrote the music with me--and I went up there and saw the first night, which was phenomenal. So that's the genesis of the music, and of course the by-product of that is that the album's going to be available on June 24th.

MR: Are you going to be distributed through Universal due to your long-term association?

PF: No, we're doing this one through RED Distribution.

MR: There's a fair amount of instrumental playing, if not songs, on this album. How did it feel playing this one back?

PF: Actually, there's only one complete instrumental on this, which is called "The One in 901." All the others might have long instrumental sections, but they all have vocals at some point. Basically, it flows. Adam Hoagland, the choreographer, said to me, "Give me a beginning, a middle and an end." That wasn't a lot of help, so Gordon and I just wrote what we felt would be good, for us and the dance. But listening to the whole thing all the way through, I'm very happy with it.

MR: Did you do any visualization as you were creating this?

PF: Not really. There were certain licks and riffs I chose specifically for movement. "Hummingbird In A Box" is probably the opening figure to that. I just visualized dance; I could see it happening, so it was great to visualize it for real when we played with them.

MR: Were you careful with the lyrics when you were coming up with them for this?

PF: Yeah, we were just telling the story of what we felt. Lyrics are lyrics, it's a story, and the choreography was definitely tailored to the lyrics as well.

MR: Because of your association and connection that you've had now with ballet, is this the first time your mind's been opened and broadened to ballet?

PF: I've always admired ballet; I definitely have a new love for it now, because I'm privy to what goes into it. Everyone loves a good dance--you've got the shows on TV everyone watches, like "So You Think You Can Dance"--and there are some incredible dancers in this country, in the various ballets. I just saw the Nashville Ballet last night. So yes, I am going to more ballets! I do appreciate the talent and the movement and what they can do with their bodies. I can barely run now [laughs], and I don't want to crouch down anymore, or I might not be able to get up! They have these bodies that they've tuned to perfection, and it's pretty amazing what they can do. I love it. I'm going to go to more ballets now around the country and hopefully around the world.

MR: Does this open your mind up to wanting to do other mediums beyond ballet?

PF: Yeah. I love anything different, you know. I've always wanted to do film music, so that's always in the cards. If someone ever asks me to do that, I'd love to do that. I'm not talking about just writing a song, I'm talking about scoring. That's definitely something I've always wanted to do. And the instrumental record I should do next... I just gotta be doing all different stuff. And I know the Nashville Ballet wants to take me out to dinner, so maybe there'll be something else for dance as well. What I would like to do is to eventually write enough work that's specifically to be performed with an orchestra. I'm not talking about just scoring some string for "Baby I Love Your Way." I've done that, it's okay, but it wasn't written with strings in mind. It's good, but I'm talking about, from scratch, coming up with an idea, talking to someone at the symphony here in town and maybe saying, "Look, I want to write this, can you help me score it for an orchestra?" I'm friends with Ben Folds, and he just did his piano concerto here in two different sets of performances; one was just with a symphony, and then he told me he was doing it again with the ballet in Nashville. He did all the orchestrating; he's brilliant and classically trained. It was phenomenal and hysterical. He put a lot of humor into the music and it was very modern. The dance was tremendous. So that made me think, "Now I want to do it differently next time." I want to push myself, do something I've never done before.

MR: You also mentioned that you're working on another instrumental project after this?

PF: I've already recorded a couple of tracks. I've got little folders of different tracks. Now that I've got my own studio down here in Nashville, the world is my oyster.

MR: You've also got some of the world's best players there, in case you want to hobnob.

PF: Well, I've done that. The very first session, I didn't know if the studio worked yet, and I'd just invite people, saying, "Look, I don't even know if this will work, but come by and have a jam." I brought all my friends from in town and we had a blast. We did a blues number. In fact it was a Buddy Guy number. We had a fantastic time and it sounded great, and it was like a "Studio warming." The beauty is that you can call someone up on a Monday and they're probably free one day that week and you're going to get a session in and get a couple of tracks done.

MR: Peter, what advice do you have for new artists?

PF: If you're unique, people are interested in you. But it's very difficult sometimes when those music business people who could bring you to the masses are looking for something that just happened. Unfortunately, if you sound like somebody else, you might have one hit or something, but if you're not unique and don't have your own style... Make friends, don't follow them. That's the way to be a successful artist, I think. Maybe in today's market, that's the wrong thing to say, but for me, I say be unique as possible and don't kowtow to people who say, "Well, we need you to do this." No. You should do what you want to do, and that's how things become trends.

Transcribed by Emily Fotis

A Conversation with Chicago's Robert Lamm

Mike Ragogna: Robert, I'm honored to speak with you. Let's get caught up with Chicago. You have a lot of irons in the fire right now, including a tour. I'm sure you're looking forward to that, huh?

Robert Lamm: Oh we are, but it's one of those things where we're always on tour so it's just a question of what exactly we're going to do while we're on tour. We started this year going clear across Canada, our second Canadian national tour in the last few years. Of course, we went across during the month of January and February, which was an experience this year, especially with all the zero temperatures. But going from there, going to a couple of concerts with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra interspersed with our first appearance on the Grammys and heading of to Europe next week for roughly three weeks and then coming back to do the REO/Chicago tour.

MR: So how long has Chicago been around now?

RL: I would say about a hundred and thirty-six in rock years.

MR: [laughs] What does Chicago mean to you these days?

RL: For me, besides the extended family aspect which it has become--and I've said this to people who were really involved with Chicago early on--I think that without Chicago there would be no Robert Lamm. I always wanted to be a composer, so I was able to develop as a composer, I learned how to arrange by arranging for Chicago, I've learned how to be a better songwriter, be a better composer, be a better musician. For decades now I've been surrounded with really wonderful musicians who continue to be curious about music and that's really what it takes. Again, I think that it's provided a growing experience for me as a person and as a musician.

MR: Why do you think Chicago continues to be popular and remains part of the culture?

RL: I make a joke about this from night to night about, "What is the reason for Chicago's longevity and appeal?" I joke that it's our dancing, but really I do think that even from the beginning, even from the context of the psychadelic sixties going into the seventies where rock groups were allowed to experiment and record those experiments and in those days FM radio provided access to those experiments, where today that's not so much the case, I think that what we contributed is this enigmatic approach to songwriting. I contend that a lot of our tracks are not really songs, they're compositions because we've always had to make room for the brass sections and percussion and vocals and lyrics, they're sort of longer things than a three-minute song, which I have no problem with. When you can write an elegant song in less than three minutes, like a James Brown tune, forget it, there's nothing more perfect than that, but I think what Chicago contributes is an approach that other people dug and said, "Okay, we can do that too."

MR: I agree with you. I remember Chicago's beginnings were so unique, you were doing double albums right off the bat. I can't think of any other act that was afforded that kind of support by a label as far as their creativity. Right out of the chute you guys were doing double albums, complicated horn arrangements that professors in colleges and kids were getting into together, and it was easy for you. Being a a kid the inspiration was different than being a mature adult. What is your creativity like now versus how you did it then?

RL: Well a lot of people haven't heard the new album because it's yet to be released, but when our manager first heard the master mixes he emailed me and said, "Why are these songs so long? You're never going to get them on radio." I said, "Peter, listen, this is really a pure Chicago album." The atmosphere in the world of music and the music business has completely changed. You'd better be ready to do anything because we're basically on our own here." I think that nowadays we are inspired by the technology and we are inspired by the wild west of the music business right now. We can do anything. We basically self-produced and recorded this on the road. You may have done that article about the rig, what we laughably call "our portable recording studio," even though it takes several people to move it around. All that is inspiring in the context of this large arc of our career where we've gone through so much stuff. Of course as a songwriter the globalness that we're all living with now is a very different atmosphere than the seventies, let's say, when we were dealing with voting rights, racial issues--still--we were dealing with the war in Vietnam, we were dealing with student protests, it's a very different situation now. There are global issues that we now have to look at and a lot of that finds its way into our new music.

MR: Wow, beautiful. You didn't lose the fire.

RL: Well we are all bombarded by the twenty-four hour news cycle. I think if you're reading newspapers or watching television or online at all there's a lot of information coming in. It's amazing how much information we didn't used to get. Of course, it's all really controlled anyway, but we do have access to so much now. It's the same with music, you have this incredible access to music in every corner of the world. Every culture in the world that's making music somehow finds its way onto the web and you can hear things you never dreamed you would ever hear. I find that very inspiring as well.

MR: Any current social issue we should be discussing?

RL: Well, I would say obviously the issue of guns in America...definitely global warming--and this is an issue that appears in one of the Chicago songs that Lee Loughnane wrote, a song called "America." It was when our party politics had descended to a new low where nothing was getting done and we had lots of pressing problems in this country last year and the two sides of the aisle could not even sit down and talk as adults. They were squabbling like grade-schoolers. Of course, the big thing is that USA always seems to be involved in some sort of conflict and the thing that's not spoken about is that it's usually about access to oil. All those things bother me and I don't want to waste your time by going down my shopping list. All those things are worth thinking about and worth raising in the context of a song when it's appropriate.

MR: Again, wow, well said. How do you think Chicago music fits into this mess?

RL: Hey listen, when we play our concerts we play two, two and a half hours, maybe thirty or thirty-five songs and there's a lot of, "You're the inspiration" and "Hard To Say I'm Sorry" and "If You Leave Me Now" and all that kind of stuff because that's what we all relate to and that's what we want to hear to kind of shut off the stuff that's going on in the world around us. I understand it's necessary to have both things.

MR: Robert, one of the projects that you worked on that I've always liked was Like A Brother with Gerry Beckley and Carl Wilson...

RL: Oh, no kidding! What a surprise, thank you.

MR: What's interesting to me is that for years Chicago and The Beach Boys almost had this cousinship going on. What was that relationship built on?

RL: A lot of it had to do with our longtime producer Jim Guercio who produced a dozen or so Chicago albums and also helped revitalize The Beach Boys. They had kind of lost their way, by the early seventies I would say no one even wanted to think about The Beach Boys. Guercio was convinced that Brian was a genius and if he could get on the right path The Beach Boys could be revitalized. It didn't quite happen the way that Jimmy was hoping it would happen but Guercio did play a lot of bass on some of those mid seventies records and really was the inspiration for the two bands touring together, which is where we met for the first time. It was a really crazy couple of years, two bands hanging out and as you say a cousinship developed. I had friendships with all of them, I'm still very close friends with Brian and as you may suspect Carl was one of my very closest friends. We had him for as long as we had him but it was really an honor to call him my friend.

MR: Beautiful. You were in a choir, too, with Harry Chapin. Do you remember Harry?

RL: Of course I remember Harry. Harry was a little older than me, he was already in college I think when I was in junior high school. All the Chapins were musical, their father Jim is a very famous jazz drummer, but I remember Harry, when he first started hanging around with the younger Chapins and the kids in the choir he was actually playing trumpet at the time. He was good trumpet player. I don't think anybody knows that. He and Tom began teaching themselves to play acoustic guitar and that was my first exposure to the possibility of small groups of musicians sitting around playing instruments. That was sort of the beginning of the folk immersion into pop culture.

MR: I've heard that phrased as "The Folk Scare."

RL: [laughs] It was a strange time, wasn't it?

MR: Hey, I want to talk about Phil Ramone. You shifted from Jim to Phil as a producer. Was it just time to move on to another producer?

RL: There was actually a business acrimony going on between Guercio and the band. It was a very good relationship and a long relationship while it lasted, but at some point, we had to walk. While we were with Guercio, Phil had done some remixes, mixed some singles for us. We had done a number of television specials in the mid to late seventies and Phil was always the sound guy on those, so we developed a friendship with him. He was a gregarious, smart, fun guy to hang out with. Just to hear him tell stories about who he recorded and what went on in those sessions was worth the price of admission anyway.

MR: You were on the stage with Robin Thicke at the Grammys, what was it like merging the genres?

RL: First of all, we didn't know we were going to do the Grammys until a couple weeks before and we had rehearse and do the Grammys around the concerts we did with The Chicago Symphony, so it was really switching gears back and forth across a couple weeks there. Our attitude was that we were a little skeptical going into rehearsals but I Googled the guy, we listened to stuff and I realized he knows his way around a studio, he had had some succes already, I thought the music he was making was worthwhile. He was very professional. He showed up on time, he was prepared, he made some suggestions, he helped us put together that little medley that we played during the Grammys. Once the skepticism was gone--on both sides probably, he probably expected he'd be playing with dinosaurs who needed to sit down to play, I don't know--after the rehearsals were over he knew we were the real thing, too. I think our attitudes were, "We can do this, this is not a problem, we've done this before." We had a lot of fun.

MR: And in the back of his mind, he had to be thinking, "I'm playing with the world's greatest horn band."

RL: He did confide that to me later on.

MR: You talked about The Chicago Symphony earlier, that must have been a very cool event for you guys.

RL: As you know, that is a world-class orchestra. A couple of the players were young teachers of their instrument back in the day when some of the horn guys were studying their instruments at the University level. So there was an awareness of the guys in the band already but we also were aware that that band, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra had won something like three or four dozen Grammys over the years. We just walked into rehearsal and said, "Listen, we are totally intimidated by you guys. Let's just have some fun." I have to say, at this point in our career we've played with a number of symphonies and The Chicago Symphony was spectacular. They rocked. Mostly the problem with symphonies is that htey can't swing, they can't rock. That group can do it. It was really terrific fun.

MR: Was that recorded? Will it ever be released?

RL: I'm sure there's already bootlegs of it around, but no, we couldn't record it or film it. Riccardo Muti, who is the main director of The Chicago Symphony attended the concert on the second night and was completely blown away. He's been chasing everybody around trying to get us to come back and do that again and film it and recorded it. I'm sure it will happen sometime in the next year or two.

MR: Speaking of projects that are or were release-challenged, Stone Of Sisyphus remained unreleased for a long time. What is that story?

RL: The story was that sometime in the early nineties, I'm guessing '93 or '94, it was time to do another album for Warner Brothers. The producer was Peter Wolf, again a terrific producer and a terrific musician. In pre-production, we talked about the kinds of songs we wanted to do. We wanted to stretch out and harken back to the way that Chicago recorded during its first albums and approach the songs that way. We did, and Peter Wolf was especially leaning on me to provide lyric content that was a little more meaningful than some of the eighties ballads. So we did all that, we put it together, we loved it, but the mistake we made was that we didn't let the executives at Warner Brothers come to the studio and listen during the process. We didn't tell them to stay away, but we also didn't invite them. There was no particular reason why we didn't, but I later found out that they were offended because those guys like to feel like they had a hand in everything. When we finally delivered the album, they essentially didn't like it, and they said, "We can't release it as this, you guys have got to go back in the studio and do some other tracks." We, at that point, were in love with the album as it was; we loved all the elements of it, we liked the energy of it, we liked the forward-thinkingness of it. We said, "Number one, we don't have time because now we have to go on the road, and number two, we like this album as it is." We agreed to disagree, we owned the album, we walked away and that was that. Cut to the following decade when we were essentially on our own and we decided to remix it and see what else was happening and we released it ourselves.

MR: That album was somewhat appropriately titled, huh.

RL: Yeah, really. Who knew?

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

RL: My opinion is that when your muse leads you to doing music it needs to be something that you would do no matter what. You need to realize that aside from practicing and aside from playing it really is a lifetime exploration. An important component to being a musician that some people don't understand, aside from practicing and playing, is listening. You need to listen to music, you need to listen also to the other guys in your band when you're playing music. I think that component gets lost. Nowadays I would say don't expect to be famous next year, or even two years from now. There are all these alternate ways that people are accessing music now and alternate ways that people are beginning their careers whether it's The Voice or American Idol or anything like that. The other day I just happened to be looking at my Shazam app and I decided to click on it and I looked at the top hundred Shazsammed artists or the week or the month and there were some artists on there I had never heard of, I never would've ever found them, I never would have found them on the radio, they wouldn't have been on television but interestingly enough there was some good music on there I really want to explore further. Having said that, you've still got to go out and play, you've still got to do live gigs and as they say, "you never know how people are going to find your music, but the only way you can be sure they won't find your music is to quit." So don't quit. Keep it going.

MR: Over the years, you've been able to donate about a quarter of a million dollars for breast cancer research for the American Cancer Society from performances. How is that going now?

RL: For a number of years now, I'd say at least five years we have run kind of an auction where the highest bidder for any given show comes up on stage and sings with Chicago. The audiences have loved it, we've raised a good sum of money for the American Cancer Society, specifically for breast cancer research. It's something that we find we usually know somebody or are related to somebody who has this disease. The treatment programs have imporved quite a bit as a result of the research but it's still something that is on the horizon, that needs to be solved. That's the reason that we got involved with it.

MR: Do you have a favorite Chicago song?

RL: I always like playing "Just You And Me" mainly because of the soprano sax solo, it gives us a chance to stretch out between Lou Pardini and myself on keyboard we have a great time grooving with each other and making that solo into something different every night. So for me that's always been my favorite song to perform live.

MR: And also with a catalog as huge as you've got, how do you even start to choose a set list for a live show or a greatest hits album? It must be very hard.

RL: [laughs] We argue a lot. We do. On the bus, backstage, in airports, you can make a case for almost any of the songs. I'm the radical guy in the band, I always want to play the newest stuff or the stuff that is the most obscure. Then there are the conservative party within Chicago who claim that if it's not broken, don't fix it. "The set worked last night" or last year or ten years ago and that's a reason to play it the same every night. Somehow we find the middle ground...unlike our congress.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with The Doobie Brothers' Tom Johnston

Mike Ragogna: Tom, the Doobies have a new album coming with lots of guests and a country vibe.

Tom Johnston: It's pretty much all based on country. It's our songs and those people singing them, and it's been a gas to do.

MR: Where did the idea come from to do this project?

TJ: It came from Sony Nashville. We had a meeting with David Huff who produced it. He brought it to our attention and said, "This would be great thing for you guys to do" and we said, "Sure, why not? Let's give it a shot." It turned out to be better than I'd even hoped. Another thing I have to mention, I'll just mention it quickly, is that playing with the studio guys we had in there was phenomenal. They were the band. If it was "China Grove," I was playing guitar but I was the only one playing at the time. If it was "Black Water," Pat [Simmons] was the only one playing, or if it was "Take It To The Streets" it was Mike. Basically, it's not like we sitting as a band and playing. The band was all the guys from Nashville. It was unbelievable.

MR: It seems the two phases of The Doobie Brothers are with and without Michael McDonald; that was the group sound. Now Michael McDonald is back on this project, what was the tearful reunion like?

TJ: We don't see him every day and we're not on the road with him all the time, but every once in a while, we play a show with Mike. We see him once or twice a year. He has a place in Hawaii, so Pat sees him a lot more than that, actually, because they both live in Maui. It's a happy reunion, it's always good to see him.

MR: On recordings as well, I imagine.

TJ: Yeah, he's got three songs on the album, "Takin' It To The Streets," "What A Fool Believes" and "You Belong To Me."

MR: Beautiful. When you look at the number of hits and influence you guys had, what kind of impact do you think you had?

TJ: I've been asked that question before and it always takes me by surprise because I don't ever think about that. It's not like I walk around seeing people emblazoned with Doobie Brothers shirts, constantly singing Doobie Brothers songs, so when I found out from doing this album just how much an effect we've had on musicians in Nashville--guys that I respect and people who are doing really well in country music and they can't say enough good things--it just blew me out of the water, I had no idea.

MR: What is it about The Doobie Brothers music that makes it so enduring?

TJ: I think it's because The Doobie Brothers is basically all about roots Americana music, and I don't mean strictly bluegrass or something like that. We come from all areas of Americana music, we come from roots, we come from rock 'n' roll, we come from R&B, americana, bluegrass and there's some country influence in there aw well. We threw them all together and that's what the band is. You've got the harmonies, you've got the finger picking, you've got R&B rhythm styles and singing styles hinting at the blues or R&B depending on what the song is, and then you've got the two versions of the band as well, you could say, when Mike was the spotlight guy, if you will, and that totally took it to another place. Yet the band still not only stayed relevant but actually became even more popular for a while. You put all that together and you've got a large swath of American music to look at.

MR: The songs on this album have really evolved over the years. Are there any evolutions that really took you by pleasant surprise? New configurations you play live now?

TJ: David Huff produced the album and he did some really cool production on some of the songs. There's a couple of tunes that are very far from what the original songs are like in a very positive way, one in particular. It was our first single and it's killer. "Nobody" is the name of the song. But all the songs have a thing that David did with them, be it a loop thrown in or pedal steel on it, this and that. You have people like Brad Paisley playing on "Rockin' Down The Highway." Nobody plays guitar quite like Brad Paisley. And on "Black Water," The Zac Brown Band, they put their own stamp on it because they're all singing on it and the track has got really cool elements that David put in there. "Long Train Running" has Toby Keith. There's a whole slew of people on here. Chris Young singing "China Grove." As far as the actual tracks themselves, that would be more of what you're referencing, the way they were cut is the guy that wrote the song is the only one that's playing on the track. If it was a song that Pat wrote he's play on it and if it was a song I wrote I'm playing on it. If it's a song that Michael wrote he's playing on it, but the rest of the guys playing aren't on the band, they're all studio guys and they're phenomenal. Unbelievably good. Pedal steel, three guitars going on every song, keyboards... And in Mike's case, probably two sets. We had bass, of course, and a phenomenal drummer. The tracks were done very rapidly but really, really well because these guys are used to working like that.

MR: You guys are taking it on the road and doing a summer tour that looks pretty extensive with Peter Frampton and Boston for part of it. Is there something about this tour that will make it different from previous ones?

TJ: Not really. I don't mean that in a negative way, but usually you get out and you play with another band and if you have chemistry with them that makes it a lot of fun. We played a lot of tours with Chicago and we always had a great time with those guys. And we've played with Peter Frampton before, but I think we've only ever played a show with Boston, just once so we don't really know them that well and we'll find that out as we're playing with them. It also has to do with the venues, which with those bands will be sheds. We just came back from doing about three weeks in Australia and New Zealand and we did quite a few festivals and that was unbelievable. The one in Byron Bay was jaw-dropping. Hundreds of thousands of people in front of you while you're playing and the list of people who played on that thing was a mile long and most of them were from the states so we kind of wondered, "If everybody's down here, who's playing in the United States?" Every gig has its own personality and every crowd has its own personality and when you're playing with another group that will affect not only the demographic but the fans of that group as well as the ones that come to see you. And it doesn't matter, as long as you're having a great time and as long as you put that out for the people and the people respond then that's what it's all about.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

TJ: Well I've been asked that a lot, and the music business has changed so drastically from when we came in--it's like night and day. Number one: Be as good at your craft--whatever that is, singing, playing or both--as you possibly can. Practice as much as you can, but I have to be honest with you, and this sounds cold but it's the truth: you'd better find somebody that's connected. Play as many shows live as possible. That's another hardship because nowadays the venues that used to be available for doing that have stunk, a lot of times you have to pay to play it if you're just starting out. Radio's changed, how you buy music has changed, how music is brought to the public as far as streaming and downloading has changed. Radio is still the same in as much as you hear it on the air, but radio has changed a lot. My advice is make sure it's what you really want to do and you're going to have to get used to the idea that you'll really have to work at it unless you know somebody who's high up in the hierarchy.

MR: What's next for the group?

TJ: That's a great question. I kind of have a tendency to live in the here and now, I don't worry about the future too much. Basically it's all about the gigs you're going to be doing. Right now the future to me is this album and the fall. We'll be back in the sheds again and that's always fun. As far as what's down the road we've got a studio album in the mix right now, 'cause we've just finished doing this and we haven't gotten into songwriting because we have been touring so much. I'm saying we've been doing two hundred seventy dates a year like the old days, we've been doing between eighty-five and a hundred shows a year at this point, but we all have families and we all have other things we do on the side when we get home, like pay bills and stuff as well as write music. For me that's my hobby, I love writing music. I like to try and do that in other genres, too if possible. It's something I'm looking into getting more heavily involved with. But the band I think just takes it as it comes. The idea of taking this album, being as how these aren't new songs, and playing them live, the thing that makes this album special is having these other artists on it and the different sounds of different artists. When we go out and play live it's going to be how it always sounded. WE can't get those people out on the road, it would never work.

MR: Obviously, you guys have a set list for every show. Is there a song on that list that when you see it, you just can't wait to get to it?

TJ: What makes those songs so special to me after playing them for as long as we have is the crowd reaction. We've played them so many times and rearranged them so many times, it's really all about how the crowd reacts. There's always something positive about having a crowd get up on their feet and sing along if they know the words to the song. It's very gratifying, and it doesn't matter if you've played the song before because it's fresh that night because of those people who are in front of you. I have songs I look forward to that people don't know. In this case because we're doing a shorter set because we're co-headlining with somebody else we're only doing one song off of World Gone Crazy and that is the song that we're doing. I love that song, I think it's a really cool tune and I look forward to playing it every night. We brought up a deep cut, we're doing "Eyes of Silver" and we completely rearranged it and it's got a big jam right in the middle of it with Marc Russo playing sax and it's really funky. That's a hell of a lot of fun to play. But I enjoy all of them! As long as the crowd's digging them, I'm digging them.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with Buzz Cason

Mike Ragogna: Let's do a little catching up with Buzz Cason. You have a new album out, Troubadour Heart, and it's already getting some action. The track "Pretend" was picked up by folk charts and "When I Get To California" went up in the Americana world. This album seems to be getting some attention.

Buzz Cason: Yes, Michael, it's kind of a multi-genre type album. For instance, the song you mentioned, "Pretend" is sort of a folky kind of song, it's acoustic, it's just myself on mandolin, Bryan Grassmeyer on bass and Amanda Contreras does a duet with me on it. It's a little song I'd had around for a while and I thought, "Hey, let's just do a little change-up on the record." The rest of the record's a little more edgy, like "When I Get To California" was recorded with Anthony Crawford in Loxley, Alabama. Anthony plays with Neil Young, he's played with Steve Winwood, he was part of the Blackhawk group, he's an accomplished musician and he helped put that record together.

MR: What was the process like recording the album?

BC: I basically produce my own records, I have my own creative workshop studio there in Nashville, it's been in Berry Hill since 1970, so whenever we feel like we've got a good song we go in and record, it makes it very convenient and easy to do a record like that when you have your own place, and I have my own band, the Love Notes which plays on a lot of the cuts. I did three cuts with Anthony in Alabama, then one cut with Jeff Silbar called "Pacific Blue" which wraps the album up, it's got sixteen vocal tracks on it, kind of a Beach Boys type esoteric-type song that wraps up the album.

MR: You also have Dolly Parton's "Don't Drop Out" as a credit.

BC: "Don't Drop Out" was a song I wrote way back with Bobby Russell, my partner who wrote great songs like "Honey," "Little Green Apples," and "Sure Gonna Miss Her" back in the seventies. The great Ray Stevens produced that record, it came out on a box set by Dolly and it gets played on the airlines a lot, I know that, and Pandora maybe.

MR: And of course I need to visit your everlasting hit, "Everlasting Love" that you co-wrote with Mac Gayden.

BC: Yeah, that's been a great song by us, originally by Robert Knight who appeared with us at the Baby Boomers Legends show in Franklin, Tennessee, on April 29th. The great Robert Knight, his photo was in The Tennessean. He had the original, then Carl Carlton came along in '74 and then Rachel Sweet and Rex Smith in the eighties and then Gloria Estefan in the nineties and right at the end of the nineties U2 did a great version of it. It's been a wonderful song for us.

MR: How does it feel to have a song like that? It's a modern-day classic, and you have so many in that category.

BC: Well my great partner Bobby Russell and I, the first song that we got recorded by Jan & Dean was called "Tennessee." We were just kids, he was out of college, I was out of high school and man, we thought, "Hey, this is easy! We might never have to get a job if it's this easy!" But we had a great mentor Gary Walker who's still in business in Nashville, he owns The Great Escape, a great vintage record shop. Gary Walker got in touch with Snuff Garrett and Lou Adler, at Liberty Records. They produced that record and it was a moderate hit and then they recorded another one of ours, "Popsicle" and that was an even bigger hit, so we thought, "We think we can do this!" We started doing that and then when Arthur Alexander recorded "Soldier Of Love," it was a highlight. Tony Moon and I wrote that for him, which is very unusual, getting to write for a particular artist. Then of course The Beatles heard him doing it in England and they did it on the BBC and the great Marshall Crenshaw did a version of it for us and then Pearl Jam did it and the Derailers did it on their album in 2011. That one has not ever really been a big single hit, but it's had a lot of lovely recordings.

MR: Buzz, do you still get the fever? Are you still writing and pitching songs to this day?

BC: I don't pitch as much as I did to other artists, I've kind of been wrapped up since about 2011 myself doing my own little Americana records. Occasionally someone will cover a song off of there, but we do some pitching and sometimes some of the catalog songs get cut. For instance, there was a cut by Dion [DiMucci] and Christine Ohlman which was an R&B song Mac Gayden and I wrote a few years back. But I have some younger folks in the office that do some of the pitching there, but I'm kind of more concentrating on my own productions and my own records and a duo called Sugarcane Jane which I'm co-producing with them right now.

MR: You're still pretty active, there's no retiring for you!

BC: Yeah, it's like someone said, "Retire from what?" It doesn't seem like work, what we do, but it really is. I've been very blessed. I've got to do what I wanted to do most of my life, so it's been great.

MR: Do you have a favorite song that you've written?

BC: That's an easy question, the song is on this album. It's called, "Going Back To Alabama," and it's a duet with Dan Penn, the great songwriter, "Do Right Woman," "Cry Like A Baby," "The Dark End Of The Street," he lives part-time in Alabama and part-time here in Nashville. Dan wrote that about our Alabama memories, my mother grew up there and I spent a lot of time as a kid down there and he grew up down in Vernon, Alabama. So we just sat down one day and reminisced and wrote this song. It recently got a very good review in England and the United Kingdom in the country music magazine over there. It's very special to me, I just love the feel of it. It was one that we were pretty much totally happy with the recording of. Sometimes you listen back and say, "Oh, I wish we'd added this," or "I wish we'd done that," but I really appreciate what happened on that song.

MR: What do you think about country music these days? It can be argued that what you're doing with Americana is more true to what the country genre could be as opposed to where it is now.

BC: You know, everything evolves, and you have a younger generation, which I think is very healthy for country music, digging the Jason Aldeans and the Luke Bryans and the Taylor Swifts and all of them, I don't want to deny them because that's their music. What's beautiful about Americana is it allows older artists to still make records and kind of get a little feel of what it was like. We always put a little retro in our records, and we also try to punch some new things in there, bright new ground. On my record we've got "Private Insanity," which is almost like a punk song, and "Something I Can Dance To" which is like a Rolling Stones song. In fact, we had Bobby Keys, the sax player for the Stones and an old friend, play on that. We're pretty much far removed sound-wise from country, but we're able to utilize some of the knowledge that we gathered coming up in that classic country era, we can utilize some of those shall I say tricks that we put into our Americana records.

MR: Americana embraces many genres. I remember in the eighties when country music started to adopt other sounds and production values, it was dismissed as "Nash Vegas" and all of a sudden, the big hats were whipped out to come to the rescue. It's almost like country wants to evolve and my feeling is that it wants to get closer to what you're now doing creatively. Country music seems like the only genre that won't allow itself to grow or evolve.

BC: Yeah, that's right. For instance, there's a song on my album called "The Call," which ironically, my son Parker Cason plays the lead guitar on, it's an outstanding lead part that he plays. It's almost as if someone in country now could cut that and it would be considered a country song, but the way we did it we felt it had an almost U2 feeling or something.

MR: You've done so much in your career, like singing background for Elvis Presley and Kenny Rogers in addition to many others.

BC: Right. I did background work for something like twenty years. I sang with the great Don Gant, who produced Jimmy Buffett and Bergan White, who's a great arranger and was with Bobby Russell and I from the beginning helping with our records and singing on them. I did a lot of background work for the producer Larry Butler, we did the Kenny Rogers records, and Mel McDaniel's great producer Jerry Kennedy. I just did a lot of jingles and voiceover work and just a variety of stuff in the studio, I loved it. It was great, I was bouncing a lot of balls because I already had my own studio and was always writing and publishing but trying to do sessions, too. I kind of had a full plate.

MR: And your publishing company is still running full force, right?

BC: That's right.

MR: And you also own Creative Workshop.

BC: That's the studio we still own, my sons are kind of taking that over. It's been there from 1970 and everybody from--Elvis' last track was cut there, "Lay On Down"--plus Leon Russell, The Doobie Brothers, Merle Haggard, Olivia Newton John, all kinds of folks have recorded there, so we're still active in that.

MR: Do you have any advice for new artist?

BC: Well, I think it's such a wide-open field with so many multiple genres that you should just be true to yourself and do the music that you feel comfortable with and find people of a like mind with you, the ones with music you're into and do your thing. It takes a lot of persistence, a lot of stick-to-it-iveness. Try your music out on people and play anywhere you can play to expose your music.

MR: What advice would you have given yourself as a new artist?

BC: Not that this is an ego thing or a selfish thing, but I think I would have been more satisfied and maybe even had a little more of a career as an artist had I focused on that. I went years without cutting any records for myself, just running the business and doing those sorts of things.

MR: It seems like beyond just yourself you've been helping out new, growing talent for many years.

BC: Yes, and I'm very proud of that. I've been blessed to meet so many great folks and be a part of their career. Like Jimmy Buffett, we started him out in 1970 and still publish some of his tunes, and we're still friends. I sang background on his first five records. A lot of the folks that came in as interns, a lot of the ladies that were my assistants went on to greater things, and some of the guys, too. We were able to kind of catapult some of them.

MR: That Jimmy Buffett connection... I think the songwriting on his early albums was solid. Is that because of your encouragement?

BC: I don't know whether I had that much to do with his creative process or not, I think if anything I might have moved him a little more into the commercial side of it, because he was very folky in the beginning. The songs we wrote for High Cumberland Jubilee which also came out on a record called Before The Beach, most of them we cowrote, and they weren't really hit songs, but they were entertaining songs.

MR: Let's get back to Troubadour Heart. After you recorded this album and gave it a listen top to bottom, what was your impression of it?

BC: I have a feeling that the song dictates how it's to be sung. I've listened to several interviews where people say, "This album's kind of all over the place, musically" and I say that my influences and my roots come from so many different fields of music that I've got a little bit of all of them on this record. I just wanted to do the vocal like I thought the song dictated. I was pretty pleased to listen to it. It took us about a year to do all the cuts. Of course, "Goin' Back To Alabama" is an old song, ten or fifteen years old, that we put in there. But I was relatively pleased with this, more than what some of the previous albums have been.

MR: Do you feel like between albums--and even as a continuing songwriter and artist--you are able to look at what you've done and say, "I'm still getting better at this!"

BC: I really have. I think since I started writing more for myself and going around doing festivals and clubs and some house concerts and getting out with the people, I believe it's freed my mind up for more songs to come into it and be turned out. Whether I've reached my peak I don't know really, I'll probably try one more time to do another record, so we'll see.

MR: Were there any surprises while recording this album? Maybe a song that took a right or left turn as you were recording it?

BC: Actually, yeah. "Troubadour Heart," the title song, was more of a novelty-sounding song when I first wrote it, it had a line in it, "Be kind to your travelling troubadour, because one day he might be your son-in-law" or something like that, but I took it in a little more serious direction.

MR: Right. You were also Snuff Garrett's assistant back in LA in the sixties, and you produced The Crickets and Leon Russell and those guys, is there any particular classic moment that makes you say, "If this hadn't happened, the rest wouldn't have either?"

BC: Oh gosh, I know that was a great opportunity for me to go out there at about age twenty-three, something like that, to California and just work in those studios. I learned a lot about mixing...and Snuff taught me a lot about producing and I got to meet artists. I got to meet Jan & Dean in person after they'd cut our songs. That was a great era right there, '62 to '64 was when I was out there.

MR: Do you feel like if that hadn't happened there wouldn't have been a corner turn?

BC: Well when I came back to Nashville I kind of had a little bit of a name behind me, they wanted to send me back to Nasvhille to open a Liberty National office and I said, "I don't think the timing's right, I just got to California, I'd kind of like to stay out here a little while. But when I came back I had a little bit more notoriety than I had before I left. So I went to work for the great Bill Justice, I ran his publicist company and then I met up with Bucky Wilkin and worked with Ronny & The Daytonas in about 1968. I've had some good turns in the road that turned out real well for me.

MR: Interestingly, they wanted you to start a Liberty National when you started out as The Statues for Liberty.

BC: That's right, we were one of Snuffy's first acts, we barely hit the charts with a song called "Blue Velvet" and then I hit the charts with Garry Miles in 1960.

MR: I've taken enough of your time, Buzz. Do you have any words of wisdom before we part ways?

BC: Well I tell you, if music's what you love, give it a shot, especially the young guys. You may just have one shot at it, and you're only young once. You have the energy and you don't have the restrictions on your life that older guys and gals do. Just go for it, be true to your music and your heart. And stay off the drugs, call mama, and always floss.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne