May 22, 2014

Chats With Camper Van Beethoven’s Victor Krummenacher, The Ready Set’s Jordan Witzigreuter, Alex Orbison and More

A Conversation with Victor Krummenacher

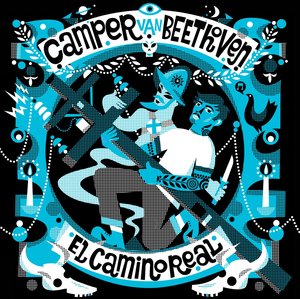

Mike Ragogna: El Camino Real, is the companion album and follow-up to La Costa Perdida, but what exactly was the link to that project? Was it recordings that occurred around the same time?

Victor Krummenacher: We had a bunch of recordings left over. When we made La Costa there were a lot of good things that got left off, they just didn't end up having a home, and we thought, "We should do something about this." It seemed like the logical continuation would be to go write a few more songs and see what we could do. We had such a distinctive theme and it was so Northern California-based, we really worked those metaphors quite a bit, but David [Lowery] and I are from Southern California and we hadn't really worked the Southern California thing, so we thought, "Let's just try it and see if we can adapt the songs in progress and write some new songs and just do something..." In a sense, La Costa... was fairly pastoral, there was a lot of Beach Boys influences and others that were really Northern California-centric, but David and I are from Southern California, and we definitely grew up on pretty aggressive punk rock music, there were a couple of things that were really, really punk rock that we had left off and we said, "Let's just see if we can integrate it, because we already have these California themes, let's just see if we can push this." So it was a pretty simple decision, really.

MR: Is that at the heart of Camper Van Beethoven, the shared experiences of growing up in the same world as David?

VK: Yeah, I think so. That's really how we relate. Camper Van Beethoven is like a diaspora. David lives in Athens, Georgia and Richmond, Virginia, Greg and I are like the last two California holdouts. Our drummer lives in Australia. We're all over the place, but the thing that we really have in common is that we grew up in the same place. It's been a lot of time, 31 years.

MR: Your group is so geographically disparate, so what's the recording process like?

VK: Well, we try and maximize when we're around. Last year, I had a full-time job and played seventy shows, and I'm not quite sure how I did that. It kind of seems like a dream now. But at the end of the touring cycle as we were going into the festival we had a show at Outside Lands and because Jonathan was out from Sweden and everybody was in the area we convened in Berkeley. Everyone had a couple of ideas and we wrote companion pieces--a lot of the work actually occurred during the composition of La Costa...; we wrote those in August. Literally it was like, "Okay, we have an hour, I have a chord progression that goes like this, do you have an idea for a riff? Okay. The clock starts now, it's one o'clock. At two o'clock we have to have a take, go." It may sound strange, but I'm pretty trustful of our ability to write. A lot of people would do this, Richard Thompson sits in his living room, the kid sits in his basement, sometimes you just have to say, "It's time to write!" I work in journalism, you know what a deadline is.

MR: Who do you work for?

VK: I work for Wired magazine, I manage their art department.

MR: So cool! Victor, let me ask you, when you guys listened back to the finished album, how did it strike you as a unique project, despite its association with La Costa Perdida?

VK: The record strikes me as more aggressive and more chaotic, which I think is more reflective of Los Angeles and its environment. Like I said, there's a little darkness in La Costa Perdida but it's kind of more rural darkness. In keeping its more pastoral feeling I think a lot of the places we were kind of psychologically living in the songs were coastal, because we spent a lot of time on the coast, and that can be a little quieter. David grew up in Redlands, I grew up in Riverside, those were hardly pastoral, it's hotter, it's drier, it's meaner, it's grittier. We both spent a lot of time living in Hollywood, so there's a touch of--are you familiar with the Mike Davis book City Of Quartz?

MR: Yes.

VK: Yeah, so it's more psychologically related to City Of Quartz than it is, say, Crying Of Lot 49.

MR: [laughs] That's really cool, I love the references. When you get together for your creative sessions, does it just lead to more Camper Van Beethoven, or does it also inspire David for more work with Cracker? How extensive is your partnership with him these days?

VK: Here's a really good example: When we were writing La Costa... and we hadn't sat and done the really fertile four or five days of sitting and writing together but we were leading into it and we had a few pieces and were starting to get a shape for the record, David emailed me and said, "Have you got anything sitting around that's kind of darker?" I had some things sitting around, and I sent it to him and then didn't hear back for a long time and I was like, "Well, hell, it was a good piece of music, I'm just going to go work on something based on that," because I do a lot of solo work. So I went and basically finished the same song, and he comes back to me maybe six months later and says, "Hey, I did this," and I was like, "Oh." So now we have two completely different versions of this song. That's just the kind of things that happens. Certainly because there's so much overflow with the bands, you never know. There are definitely things that Cracker has done that influence Camper, and there are things that Camper has done that influence Cracker. There are definitely things that both those bands have done that have influenced everybody in the band in their solo work.

One of the things that we always do, we had this longstanding side project with the lead guitar player of Counting Crows called Monks Of Doom which is kind of the prog rock alter ego of Camper Van Beethoven where the King Crimson influences came out and time changes and really aggressive, strange music. Sometimes David is with me and he says, "We have to bring some Monks into this." I think the older we've gotten we've started to realize at a certain point, "I'm not going to be here forever." We're extraordinarily lucky to be fifty and still be doing this. most people I know my age don't do it anymore and don't have an audience, because the music business is so screwed up. I think the biggest problem with Camper is that we have too many ideas and want to do too many things. At a certain point you have to make peace with it and find the strengths from it.

MR: Well how do you feel about the future? This is a comfortable fit and when you guys get together?

VK: Yeah, I think that's kind of how it has to be. If I got into predicting the future I don't think it would work anymore, it's not a predictable business model, right? I know people who are more famous than me and have trouble getting their records out. A friend of mine took me to meet David Crosby a few weeks ago and he was basically saying the same things that we say. "I'm not making any money and this is really difficult and it's hard to get a record out." I look at that and go, "Wow, that's David Crosby." I think Camper did its part, we made some great influential music, I think we really did change how people perceived and listened to music when we were first a band and everything we've done since is kind of icing on the cake. My one condition with the band when we started playing together was that I don't want to be a nostalgia act. When we get to the point where we're a nostalgia act I'll just not do it, you can get another bass player. We have to have new music and it has to be active. That's my situation. It's just kind of what works. "Where can we make some money and how can we do it?" Otherwise I just consider myself lucky. Let's not forget the future 'cause we can't.

MR: You guys are very proud of the work you do with Camper Van Beethoven, aren't you?

VK: I'm very proud of the band. I'm really proud of the fact that we made good music that people still like. One of the things I'm most proud of is how much it means to people. It's almost a weird burden on some level because every set we have to play "Take The Skinheads Bowling," but we have people come and they bring their children and the children are adults now and they sing along and say, "I grew up on this music." To have it still be relevant to people and play "All Her Favorite Fruit" and someone starts crying, it's pretty touching to have been part of it and that it means so much to--it's not a big group of people but we have a small but dedicated group of people. I put out a solo record and five hundred people will buy it. That's not a lot, but it keeps it going. A lot of people just can't do that anymore. There are a lot of things I wish were different, I wish the music business still existed, I wish that people weren't completely pressurized into being on the road, I wish people cared about albums and content and didn't look at their phones so much and spent more time reading books, but you can't change that stuff. You just can't do it.

MR: Victor, what advice do you have for new artists?

VK: My advice is to do whatever you want to, because that's what I did. Put your heart and soul into it and mean it and don't compromise. Just don't do it. When I make a record, it doesn't matter who I'm making a record with, these conversations come up where we're talking about compromising for the record company or other people's tastes and I'll disengage. I'm not interested. Your art has to have your complete integrity and if it doesn't there's just no point.

MR: Do you have any favorites?

VK: You know, I have my favorites. The Virgin that Camper did were re-released by Omnivore earlier this year and as a result I went and relistened to them and I feel really, really strongly proud of those records, I think they were really well-executed, they were very hard to make and it was a very hard time to be in the band but I think they really stand up and they should last and serve as influential records. The first Camper record we had no idea what we were doing. It's like The Modern Lovers' first records, they didn't know what they were doing, they hadn't got a clue, it was still completely unique. I think there's some great Cracker records, I think Kerosene Hat is pretty marvelous still and I think that Golden Age is really quite amazing. I think La Costa... just kind of proved that were still totally violent and creative, maybe long after the fact that people had said, "Are they going to be like 'X' and not play anything but the first few records?" It'd been eight years since we put out a record and I think if you want to dig deep there's a lot of cool stuff in the solo realm from pretty much everybody. If you want to get deep with Camper stuff there's a lot of places to go and I think there's a lot more good music in there than just the high points that people know.

MR: One of the interesting things about Camper Van Beethoven is that it's always cited as having been influential. Do you think that's true?

VK: Oh yeah, I think so. I think you see it in Pavement, I think you see it in Cake, that kind of absurdist sense of humor that seems to percolate through culture, people were very earnest when we came along. The whimsical bands were either like the B-52s which was pretty camp or things like The Fibonaccis who were this Los Angeles new wave art rock band. It was all either very campy or very esoteric and high brow and we were just kind of a circus which harkened back maybe more to things like Country Joe & The Fish or some other sixties bands where there was a little bit more of an educated mindset but not elitist, you know? We're from the suburbs. One of the first reviews that I remember that really rubbed me the wrong way was Spin magazine saying of Telephone Free Landslide Victory, "Don't these guys realize there's no culture in the suburbs?" [laughs] It still pisses me off. What a really, really horribly arrogant thing to say. There's a lot of culture. Culture is where humans are. Just because it's suburban... I think what we did is that we opened up the door to not being from "the right place." We're from Santa Cruz, we're from Redlands, we're from Riverside, we weren't from San Francisco, we weren't from New York, we weren't from LA. In the way that R.E.M. was from Athens we were able to do a California analogue. There was a lot of affinity for bands at the time like The Minutemen and the Meat Puppets and things like that, like all good revolutionary groups we didn't sit and talk about it, we just kind of did it. But we understood the kindship, I think we all instinctively understood where we were coming from and what we were doing.

MR: You also played with Cracker. What do you think about Cracker?

VK: They're recording some stuff right now and I really want to hear it but he hasn't played it for me. I mean, I've been busy and he's been busy too, it's a nudge, but I'm not really pissed about it. When the band broke up it was a bitter breakup and I was very much off in a different world, I didn't much care for what they were doing because I wasn't listening to it. When David and I reconciled I had to go listen to it and learn how to play it and my respect for it went way up. There's a lot of subtlety and a lot of nuance to what they're doing. When Cracker's at its very best it's got a lot more going on than I think first meets the eye, I think people always see it dumbed down compared to Camper but it's not, it's actually slyer than that, it's smarter than that and musically, especially, there are certain people who played in that band who did remarkable work. It's pretty deep. It's a longstanding relationship. I still don't always get along with or agree with David, that's just how that works, but if you don't have a tension then nothing goes on. If we all agreed... The last thing I want to do as a creative person is go into a situation where everybody agrees. It never works.

MR: And what two brothers haven't fought with each other?

VK: Exactly.

MR: Is there anything else you'd like to mention?

VK: No, just that in regards to El Camino Real, we didn't really plan on having a record out so quickly and we're all kind of happy that we did. It's nice that it's working.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with Alex Orbison

Mike Ragogna: There are so many releases oriented around your dad's work and his catalog right now, and one of the major releases is the deluxe edition of Mystery Girl. What was your participation in that and how do you like the end result?

Alex Orbison: Well, Mystery Girl Deluxe happens to fall on the 25th anniversary of the annual release. My brothers and I put this together, we all had our parts. I directed the documentary Mystery Girl Unraveled, which is the camera part to this. We started with archive footage that was very strong. A bunch of it we did not know that we actually had, there were recordings that we'd found in the last two years that really made the documentary appealing for us. We have behind the scenes footage of the guys recording all through Mike Hammel's Garage and then in Rumbo studios with archive interviews from and Tom Petty and Mike Campbell and Steve Cropper among others. We're really, really proud of that. On the audio side, we have nine bonus tracks which are studio demos and in studio jams more or less. Some of them are just the band and my dad running through the songs before they were doing the takes, and then we actually have very intimate demos that are blue box recordings from my dad. Out of those, one of them has never been heard before. One of those songs had such a beautiful sound, but the tape was unlistenable, so we used new technology to go and scoop out just the vocal and be able to turn that up and put new instrumentation on it.

My brothers and I are all musicians, so my brothers and John Carter Cash and I played on it and then my brothers and I sang backup and John Carter coproduced it with us at the Cash Cabin in Hendersonville, Tennessee. There's so much to this deluxe package and the forty page booklet that has a five thousand word essay and never before seen photos and all the original artwork. We tried to only add and not take away, keep things in that original format from the late eighties. It's been very exciting. We're really, really pleased with what we came back with. The expression is, "Everything but the kitchen sink," we've been calling this "The kitchen sink." We just wanted to see how much we could put on a CD and with the documentary we just started where we started and did it primarily for the fans. It's a real nice little piece.

MR: Can you tell me the story of Mystery Girl? Were there any surprises about your father when you went through the archives?

AO: The footage is very, very candid at the Mike Campbell studio. It was just a camera that they set up because the control room was in a guest bedroom and my dad was recording in the garage. The footage is very candid and the personal details we all remember very, very clearly but the actual technique that they used to record Mystery Girl and specifically "You Got It" and the Mike Campbell songs, this stuff came out sounding so amazing and they were literally in the garage and they liked the sound underneath the light that goes on the motor that pulls the garage door up. So they would literally pull the cars out and set up everything from my dad's vocal to the drums and they would just go for it right there in that garage. I knew that they did some stuff there but I didn't know that they did everything there, and that was very, very surprising to me. Also "She's A Mystery To Me" with Bono and the Edge, we remember Bono coming by the house and seeing him and discussion was a big deal, but I did not know that Bono had gotten my dad into the big drum room at Rumbo studios. He had his guitar amp in that big room with the drums going and my dad singing the vocal and I had no idea that they had such an unorthodox approach. They had the chance to go to the big studio that was all polished and they huddled in one room like it was the garage.

So the intimacy and the actual technique they used was so much different than anything that I'd imagined while listening to the end results of "You Got It" and "She's A Mystery" and the actual polish on the record. There's also TV footage from the Netherlands, a guy who came and interviewed my dad and there's footage of the song "In The Real World," it had aired in the Netherlands but I had never seen it. I ended up seeing it on YouTube some time in the last year and contacted them and got that footage. To have a live performance of my dad singing one of these special songs was really incredible. I'll go on about the record: Mystery Girl was started in 1985, in late '84 Jeff Lynne came to Hendersonville, Tennessee, where we lived at the time, where Johnny Cash fell in the lake. He wanted to get together with my dad and talk about doing some recording and writing some songs and putting a record together. We had moved to Malibu, California within a year and when we got to Malibu my dad started to put together a team with a publicist and start recording other stuff that was not the new record. He did Class Of '55 with Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis and then he went and re-recorded his greatest hits because Monument, the label that put them out originally went bankrupt and the fans were unable to get those recordings of the classics.

He was doing that and David Lynch had put "In Dreams" into Blue Velvet. He went and recorded "In Dreams" with T-Bone Burnett and T-Bone was introduced and my dad signed with Virgin records at the same time. Then they recorded the first song from Mystery Girl sometime in 1987, I want to say. Right around then they had the "The Comedians" and the black and white special, and that was a good glimpse at what Mystery Girl would look like live as well. The first songs were done with T Bone Burnett and then at that point I think T Bone had another project and my dad sent out for Jeff Lynne again and Jeff did a little part on "You Got It" and "California Blue." Then The Travelling Wilburys happened and that footage ended up in the documentary. In "California Blue," George Harrison shows up...then The Travelling Wilburys happened right in the middle of my dad's record. Jeff also did a song that they wrote together called "A Love So Beautiful," they did that during the Travelling Willburys while normal people were sleeping Jeff had constructed that song and my dad sang it in one take, there's a beautiful piece on that in the documentary. After the Travelling Wilburys my dad came back and grabbed Mike Campbell and they went into Rumbo studios and cut the song "Windsurfer" that my dad wrote with Bill [Dees], a song called "In The Real World," the last song on the album "Careless Heart" was done there as well and then after that Bono had come up with his song and they went back to Rumbo and they had a magical tracking session there, Bono and my dad and Jim Keltner as the drummer, you can hear it on that tape, it's magical. My brother Wesley actually wrote the last recorded song on the album, it's called "The Only One."

My dad had talked to Wes, who had started writing songs, and he submitted three songs and my dad picked "The Only One." My dad had closed out that record with my brother's recording, basically it was Roy Orbison and the Heartbreakers, he used Tom Petty's band for a lot of this stuff but that one was from Memphis Hall so it ended up being a really special track for us. That was late in 1988, sometime around November, so my dad spent a couple of weeks out mixing and mastering all of the songs with the different producers. My mom and dad actually produced "In The Real World" and Mike Campbell did all the other songs and Jeff Lynne and T-Bone worked on it and even all the different engineers were different for that. To get everything into one sound my dad spent a long time doing the mixing and mastering himself. It's interesting because over time people have imagined that my dad cut the record and went back to the Wilburys because they had become so successful and that he passed the record off to someone else, but my dad actually had the test pressings from Mystery Girl and played it for everyone that he saw by the end of November there. That was a really great page from the documentary, I wanted to show how much fun everyone was having and what a great experience it was in the making of the actual record. It really ended up being a nice timeline and I was surprised by how much footage we had of my dad through this time.

MR: At that point in time, Roy Orbison had almost never been more famous.

AO: It was wonderful that he had made a point to be more publicly visible. As contemporary as he tried to be, he ended up making a record that sounded totally classic. If you listen to this next to the other albums of the time there's not a lot of that eighties funky electronic heavy synth keyboards and stuff. It really was magical, the genesis of it was very organic and I think the timing was just right. I think everyone knew it was going to be a big deal and they felt it was going to do well. It was amazing. Personally, I attribute a lot of this to the move to Malibu, California. There were always people who came by Hendersonville because Hendersonville was a little beacon of safety when you're touring. Nashville is centrally located so if you end up in Kentucky or somewhere then why not drive the extra three or four hours on the bus? For someone like Bob Dylan to come to Hendersonville in the middle of a tour happened a lot, but when we lived in Malibu people started to realize, "Hey, Roy Orbison's in town, why don't we just call him and get him over here?" Everything from hearing Bruce Springsteen sing Happy Birthday to my dad and my dad during the national anthem and going to the Hard Rock for just random parties and stuff. He was getting out and being a public figure which hadn't really happened for quite some time. It was part of his diligence to get out there and be seen and also put together the right team to get there.

MR: Was Roy aware of his contribution to culture? And how did you view your dad's place in music history?

AO: You know, when I was very, very young I could tell that were just a different type of family, and we were, even outside of my dad. It just seemed like we were all different from other people. Then I started to realize around age four or five that my dad was really special and the nature of his performances were so incredible that I was a fan from that point on, I went to all of those shows from that point on just to go see him do his thing and hit those high notes. It was such a spectacle and an event, every time he would start off on "Running Scared" and get to those high notes, it was like watching a stunt. It almost seemed like it couldn't be real. With the writing at home and the people coming by and the work that was being done, that was so steady through my life that all seemed very normal. It's funny that you mentioned Chris Isaac, I remember Chris coming by the house and he was with us for a couple of days, literally he would come by mid morning and we would have lunch together and he would sit around the table with us at dinner time and he and my dad would walk across the street to the beach and talk and have guitars and they would go over stuff. There was definitely time spent with so many people in that manner that it all just seemed really normal. It's amazing, the amount of people that my dad touched throughout his life all the way from Nashville, Tennessee, producing people through the sixties, I went through his schedule, he would be touring and then I'd see these albums that my dad produced and I would look back and say, "Wait a minute, that was when 'Pretty Woman' was out on the charts for four weeks," because it hit the number one slot twice, once at the end of summer and then again in fall. In the interim my dad went back to Nashville and produced another band's album and went back when "Pretty Woman" hit number one again. So seeing the scope of the work and the extent of it is really incredible. My dad's opinion on it, he was a humble, gentle soul, and in the documentary we made I think we relayed that more than probably had ever been seen before.

His expressions about people's admiration, he'd say a lot of these things, but I know he was deeply touched by all that. It is really amazing because these people that my dad touched ended up resurfacing and joining around him and being the creative base that my dad was able to use to have his resurgence and really creatively have the most freedom that he had ever had and be the most effective with that absolute freedom of creativity. He was in admiration of them and the thing that I find interesting is that everyone was on equal footing and my dad just saw eye to eye. It's Jeff Lynne, my dad and Mike Campbell and everyone had an equal vote and it was just really democratic and easygoing. I saw Bono and my dad writing together and they were just like two guys. There was no before or after, everyone was just right in that moment and working as a team. It's a great thing to be able to see a little bit of that.

MR: You talked about Chris Isaac, I wish we had gotten to see a duet between them.

AO: Yeah, yeah. And when my dad and Chris actually toured together with Dizzy Gilespie, Chris opened up in Saratoga, California. I'd say that was 1987, so things were really cracking. My dad had started recording and the k.d. lang duet was the last thing of that nature before my dad was a hundred percent concentrated on making the new stuff. The duet with Chris would not have come until probably the end of '90 or even '91, it would have taken another year for my dad to slow down from putting together Mystery Girl and the next new album that he was really excited about. So yeah, it does seem like a missed opportunity, but when you look back through the career--I saw a picture of my dad and Otis Redding on the same plane and they were talking about doing "The Big O's" because that was both of their nicknames. They laughed about that, they became friends so fast on that plane ride that they had planned to do a "Big O's" record. If you start following that "lost opportunity" thing you can really go down a wormhole. [laughs]

MR: I just mean to say that it's like the James Taylor and Carly Simon album that never happened, moments in history that would have been terrific.

AO: Oh, of course. I completely understand. There's several of his friends that I wonder, "Why didn't that happen?" but we do have more of those things that are relatively unknown, Roy Orbison penned songs that Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Holly cut, and the connection with the Johnny Cash songs and stuff that's not far back, when it comes to light it's really cool to piece together these pictures. Part of what we've done with the Mystery Girl Unraveled is get a good visual representation of what was going on and chronicle it in the liner notes. It's really the first time that this part of the career has ever been in order from 1985 until my dad passed away, because everything did happen so fast. It's really cool to see the way everything unfolded.

MR: Alex, what advice do you have for new artists? And what do you think your dad might have had as advice for new artists?

AO: I think being a new artist is almost tougher now than it was before. I would say that being able to change with the game is very important, but you have to maintain integrity through that, so that's a real fine line to be able to do. I know my dad started as a lead guitar player in the middle of the fifties and did that exclusively and then was singing a little bit and then quit and became a songwriter and not a performer until he pitched a song to Elvis Presley and that song was called "Only The Lonely." Elvis asked my dad if he could come by the next day. It was very late at night so my dad drove all the way to Nashville and cut "Only The Lonely" himself and ended up having the smash hit with that that changed his career forever. That kind of thing is good, to stay malleable but also have integrity and know if your position changes or whatever your creative outlet is or even your instrument or anything, I was a drummer for years and years and I had tried to learn as much as I could about the music industry and it's really paying off now that I'm taking care of my dad's stuff. It's very helpful to know both sides of the coin. My dad's thing was "Practice, practice, practice." He told it to me, he told it to Roy Junior and he told it to Wesley. I said, "I'm practicing three or four hours a day," I was practicing much more than that usually but he would say, "I would do eight hours a day of singing and we would have rehearsals before that," so my dad was singing as much as twelve hours a day through the fifties and early sixties.

Practice does make perfect and for us that was the only way to get there. So I know that's what my dad would say because that's what he told me. I got to the point where I played the drums so much it affected my school performance. So that's the clear-cut path to doing it: Start with that and get that strong base of really going over stuff. But it's almost like the stock market; you need to diversify your practice, there's practice at home where you're practicing your instrument and your craft and then there's practice with a band which is rehearsal and preproduction for a record is super, super important. I could hear that through my dad's stuff, we would work on it before he would record it and really try to figure it out and then practicing the final product and going on the road with it. There's a lot of practice involved, I think.

MR: Van Halen had a hit with "Pretty Woman" and others have covered your dad's material. What did Roy and your family think of some of the covers that have been recorded over the years? What were his thoughts on the finished results?

AO: We had the Van Halen "Pretty Woman" single. My dad listened to that a lot because the big stereo was in the living room. When he came home I don't even know if he was aware of it yet because we had caught onto it very quickly. He thought it was great. He was always quoted as saying, "Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery," so when people would recreate his music it was a way that the music was living on and having younger fans hear it and it was just the highest form of compliment. With all the people have cut his songs, it's a pretty wide swath from Ronstadt and MacLean in the seventies all the way to newer bands and people you would never imagine to cut Roy Orbison songs. I think the number of covers is in the thousands, twenty-five hundred or thirty-five hundred different versions of different songs in different languages that we've collected over the years. It's really amazing. He was very, very flattered by that and I think that's another nice part of his nature as a person.

MR: What do you think might have been or was his favorite song that he'd ever written or recorded? And what did your family like the most?

AO: We were all so goo-goo over Mystery Girl, probably because I know that he enjoyed all of the songs immensely. The fun thing to me was the actual parts of the songs. There's a song called "California Blue" and Jeff Lynne has this light effect in the back, the name of it is actually "Bubbles" but it doesn't sound like bubbles. My dad was singing the vocal part and then when they finished the song it wasn't really in there. You can actually hear him humming it in the documentary. When Jeff mixed the albums he put this little ascending keyboard part that goes up and my dad was just tickled pink with the bubbles, that was all he talked about for days. He would play it and just listen to it. I think he was missing the forest for the trees, he focused on the little things that were making these songs that he was comfortable with and enjoyed. The little things made it for him. I think that's a little different than looking back in retrospect and saying, "This song was my favorite." I know that the earlier works were such masterpieces, my dad wasn't really like that, though, he didn't really look back. He wasn't ever thinking about "The glory days," he was always focused on moving forward, especially with recording. It's great that the newer songs had such similarities, the essence of "California Blue" is somewhat "Blue Bayou"-ish, and that kind of matches with the up tempo-ness of "Pretty Woman" and "In The Real World" is what happens in the real world and "In Dreams" is the other side of that. There is a kinship to the earlier stuff. They're little tips of the hat to each other, but now that 25 years has gone by, looking back in retrospect and seeing how this mystery girl album has stood up over time, I was just in Europe last week and I met several people that knew "You Got It" but didn't know the name Roy Orbison or the song "Pretty Woman," but I said, "You Got It," and they said, "Oh, yeah, yeah!" and I said, "That's Roy Orbison." That's really amazing to me.

MR: What do you think is the Roy Orbison legacy?

AO: The Roy Orbison legacy moving on from here?

MR: Yeah, how do you think he will be remembered decades from now?

AO: I hope that in a decade from now more people know who Roy Orbison is than ever before. I believe it's possible, and all joking aside it's pretty remarkable, he's got very good days ahead, and we three brothers have been having good days. It's very important to us.

MR: Is there anything else that we should know about Roy Orbison? Something that didn't even go in your documentary?

AO: He was absolutely the funniest guys in my entire life. Having the dark glasses and the dark hair, that wouldn't be the first thing that you thought, but it's true. Aside from being one of the most special and overall really nice across the board people, you never find someone of that stature, where one hundred percent of the stories we got back were about how nice he was, even people who had casual encounters with him in airport halls all the way up to Jeff Lynne it was consistent and that is really amazing. That's something that normal people wouldn't know because these are all stories that have come back to me one by one, but it's amazing to go through everything he went through and do the things he did and still be a good guy.

Transcribed By Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with The Ready Set's Jordan Witzigreuter

Mike Ragogna: Jordan, your latest album The Bad And The Better was produced by Ian Kirkpatrick. What's the band's process in the studio like with him?

Jordan Witzigreuter: My process with Ian is very laid back. I had already finished a lot of the songs before going into the studio with him, so it was a lot of editing and double checking to make sure we agreed that everything was written as cohesively as possible, and honing in on small production things. We wrote and produced couple of songs from scratch as well, so the process really varied on a song-by-song basis. Ian is great at making sure that I don't get too carried away on one idea, and explore every other possible way of phrasing or delivering something before I commit.

MR: Can you take us on a tour of the album's material, like what was it like writing the material and do any songs have an unusual or particularly unique origin?

JW: I wrote a bunch of songs -- 70 or so -- over the past two years, and only a few of those 70 were even considered for this album. I tend to like a song when I finish it, give it a week, and then I'm over it, so the ones that made the cut were the ones I still felt passionately about. The album is about 40% of those songs, and 60% songs I wrote in the studio while recording. As far as origin goes, I actually finished the song "Fangz" quite a while after the album was finished, and I didn't know if I planned on using it as a TRS song or as something to pitch to someone else. When I switched labels, from Warner Brothers to Razor & Tie, I had to chance to change things, add songs, and go back through the music to make sure the album was what I wanted it to be. I remembered Fangz and thought "this song is kind of weird for me, and I know there would be no way it would have been approved before, but I don't have to worry about that now". I recorded and produced it myself at my place in LA instead of at a studio. It was strangely liberating to just make a decision like that without having to get approval from 100 different people. At the end of the day, I think my fans will like it, so it makes sense to me.

MR: Do you have a favorite cut among the tracks, which is it and why does it resonate with you?

JW: My favorite song is "Are We Happy Now?" It's about me chasing these external forms of validation for happiness -- crowd sizes, song sales, chart position, radio play, etc., etc. Those are all really important things of course, but when you're someone who has always been very goal-oriented, those things can become huge weights, especially if they don't live up to your hopes and expectations. It reached a point where even if something amazing happened, I would be too caught up in worrying about next step toward reaching an "ultimate goal" to even appreciate it. The craziest part is that chances are, that goal would shift to something else as soon as it was obtained. In the simplest sense, it's about stopping to smell the flowers. The present moment is where you find happiness, because that's all we actually have, and it is amazing. The future is always going to be the future.

MR: What is it about the themes within The Bad And The Better that you can relate to the most?

JW: The best way for me to describe the overall theme within The Bad And The Better is to explain why I named the album that. The Bad And The Better symbolizes perspective. There is an inherent element of bad in every good, and of good in every bad. It's all in the way you choose to see it. The idea of that comes through in some of the songs, like "Higher," "Are We Happy Now," "Bleeding," etc.. When I was writing the album, perspective and my decision of how to interpret things shaped a huge turning point for me as a person.

MR: When you look back at the guy whose band had a hit with I'm Alive, I'm Dreaming five years ago, what are some of the biggest challenges and biggest evolution you've had since then?

JW: I feel like I learned how to write songs again. I had a loose grasp of how to write a song five years ago. Now I am more confident, but I'm still learning. I got to write with incredible people, like JR Rotem, RedOne, some of RX Songs camp, and a ton of others. Every session i would go into would feel like class for me. I started touring straight out of high school and didn't go to college, but after spending all that time working with incredible people, I feel like I attended some kind of "real-world-experience-songwriting-college". I'm really lucky I was able to do that -- it taught me how to trim the fat on songs, how to make the best parts stand out, and really edit myself while I write and work on tracks.

MR: What are a couple of your favorite moments of The Ready Set journey so far?

JW: My favorite moment of all was probably the first time playing at an arena. it was a radio festival in Minneapolis, it was sold out at 14,000. We opened the show, but had never played to more than 2,000 people up until that point. The funny thing is that I had no idea it was even that big of a show, like I didn't put it in perspective until I walked out on stage. 2 years prior I was playing to 50 people. I felt really lucky. Another awesome moment was getting to play in Manila--I had no idea I had fans overseas, let alone ones as passionate as them. You really feel a lot of love in other countries.

MR: You went on tour with Maroon 5 and other major acts which initially got you big visibility. Do you return the favor and try to help out bands or acts that are just starting out?

JW: I love bringing smaller bands on tour. The first time I got to be a part of a real tour was with Boys Like Girls headlining. They treated us so incredibly well--their crew helped us with gear, their sound guy ran sound for us, and they definitely didn't have to do those things. I always hope that after a band tours with us they feel that we treated them well. It's not as common as you might think, but it really does go a long way to be as nice to everyone on the road as possible. When you treat people poorly, word spreads like wildfire.

MR: Jordan, what advice do you have for new artists?

JW: Put 100% of your energy into making it happen for you. Ignore all naysayers, spend all your time on your art, and fully devote yourself to it. Have a plan and a goal in sight, and do everything you can to convince yourself of it's reality. Don't worry about how you will make it out of your current circumstance to succeed, just do everything you can where you are at that time to get yourself closer to where you want to be. It's always a step-by-step process. Don't get caught up in let downs or failures, everything is part of the journey. The seemingly worst situations make the best stories down the road, usually!

MR: What musical or creative goals do you have for The Ready Set?

JW: I actually have just started getting really excited about the idea of starting the writing process for the next album. I have a lot of things I want to do, and I think the door is really open for me right now. I have an amazing team with my management and new label Razor & Tie, and I think creatively, everybody is truly on the same page in a big way. My goal has always been pretty simple--put out music I love, play that music for as many people as I can, and maintain the same excitement and passion I felt when I started this. Right now I am pretty excited.

LOVES IT'S "DANCIN'" EXCLUSIVE

photo credit: Laura Partain

According to Loves It's Jenny Parrott...

"'Dancin'' is about the journey of a young emotionally vulnerable woman who goes out to find love and to try and fulfill her potential. More specifically, it's an autobiographical song about my first love, my music, my dreams and the loss, crisis and ultimate resolution that followed.

"My first love was a wonderful musician who invited me to move away to Nebraska and front my first band. It felt like someone had given me the helm of an awesome fireworks show. The problem was that everyone seemed to notice that he was an alcoholic but me. I was 19-years-old, and had been raised by an alcoholic mom with similar behavior.

"My dad didn't want me to go, but my boyfriend was the first to see the singer and songwriter in me that I wanted to see in myself. But, when he wasn't sober, he did the things that we know addicts do and I didn't manage to face it until the end. My dad saw this from the beginning, but I was so caught up with being in love.

"I was blind at the time, but in the end there was resolution: the song concludes on a compromise between father and daughter where he shows his love and approval by buying her dancing shoes. I dreamed my dad took me shopping, and it meant that everything was okay and he could rest somewhat assured that I wouldn't make any more horrible romantic decisions. In the actual dream the shoes my Dad bought me were bright orange platforms!"