September 4, 2014

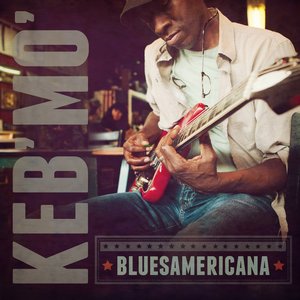

BLUESAmericana & Beyond: Chatting with Keb’ Mo’, Richie Kotzen, Ishmael Herring and Warren Cuccurullo

A Conversation with Keb' Mo'

Mike Ragogna: Hey Keb', how have you been since our last chat?

Keb' Mo': I've been good. I've been on the road, doing the road thing, having fun, playing music.

MR: You're touring with G. Love, right? What kind of shenanigans have you two gotten up to?

KM: [laughs] Shenanigans? G. Love is way cool and I'm very sedated. [laughs] We play a little music, he comes and plays a song with me and I play a song or two with him. We like to hang out afterward and have conversations, we have nice little jam sessions in the middle of the night in the back of the theatre in Alabama. That was fun.

MR: When you're on the road with these guys do you ever sit with them and write a song or two?

KM: No, it's kind of hard because he travels on his bus and I travel on mine, and when he's sound checking I'm waiting. I don't really write on the road myself. I wait 'til I get home to write. I like to really live on the road and then I come home and do some writing there. I think I wrote a song on the road with Zac Brown. But I've only written one or two songs on the road. I like to just be on the road.

MR: Let's talk about your latest, BLUESAmericana. Americana has become associated with a "rootsy" sound. But I think that term--Americana--should apply to American music like the blues.

KM: I agree. I was at an event where we were listeningn to music and we were listening to some Allen Toussaint and someone said, "That's not Americana," and I said, "What do you mean? That's more Americana than anything we've listened to so far today." That's the result of a preconceived notion of what Americana is that that person had. I think a lot of people are jumping into the Americana genre because it's not a genre, it's a place where if you have no genre you can go to Americana. "I'm not really bluesy enough to be total blues, I'm not country enough to be totally country, I'm not folk enough to be totally folk, I'm not R&B enough to be R&B," you can come be Americana.

MR: Maybe it's like a club.

KM: It really is! I think it's a place where a lot of people are gathering in the genre to let music just be music. I know some jazz artists who are jumping in there. I think it's really kind of a neutralizer for music. I don't think that's what they meant to do when they started it, but I think that's what's happening for me. I named BLUESAmericana after them. I liked the Americana genre, it was more like alternative country the first time I went to the awards. I called it leftwing country. Americana, that's a pretty broad name, there.

MR: I think there's even a place in Americana for people like Bonnie Raitt; she's uncategorizable. She's mainly the blues, but she works with so many other genres, what do you do with an artist like that? She's not totally blues.

KM: No, she's not by any means. Never has been.

MR: So how did the material come together for BLUESAmericana?

KM: The biggest difference on this one was our first recording of it. It was completely upside down, which I think is actually right side up. I started with the vocals. I recorded the vocals first, with nothing on it.

MR: You sang a capella?

KM: Yes. I sang with nothing. I had a click track behind it so I could hold a time reference, but I just sang the song. Being that the lyric and the melody was the first thing on it, everything else that went on had to really adhere to that. There was no stepping on it. If I put the rhythm track on it first I may be singing on down but maybe it's right for the vocal or maybe not. I did a lot of the playing myself, too. It really worked. The next thing I put on was the guitar and the drums. It was very, very much all about the vocal.

MR: You have perfect pitch?

KM: I don't have perfect pitch. I have horrible pitch, actually. What I did was I would keep a reference of the guitar next to me and I would pluck the key periodically to make sure I wasn't drifting sharp or flat. I went back and sang them again after it was all said and done, but having the vocal on it first thing was a really interesting way to approach it. It was just really cool. I think I'd like to do that again.

MR: Do you want to continue what you did on BLUESAmericana? Is this how you see Keb' Mo' in the future?

KM: Well I found that I have to be really careful about deviating too much from the genre. I did a piece on my last record called "Reflection," which was met with very mixed opinions. I was like, "Okay, I did that, I can do that," but I can't really do a whole record of it without giving the audience something to hold on to. James Taylor is always James Taylor. Metallica is always Metallica. The sad part about being an artist is that once your audience likes who you are--you go to McDonald's and get a burger, you want your Big Mac to taste like the last one you had. I'm not saying that I want to be a McDonald's-type artist, but if I want to keep communicating--and my ultimate goal is to keep communicating with the audience--I shouldn't try to take them so far that the go away and can't get it. The objective is to communicate. So the next time I think what I want to do is something that feels good and is kind of acoustic and classic in nature but I'd like to attack the song with [tight singing? 10:54] That's part of my thing. Singing is always the most challenging thing for me. That's what I don't really want to do.

MR: When you put the vocal down first did you discover anything? Do you think you learned some things about your voice, hearing it stand alone?

KM: I'm so familiar with my vocals, I know everything that I do that's screwed up. The trouble with me is I know how a great singer is supposed to sound. I grew up in the baptist church in southern California with all these great singers. Every church had a Marvin Gaye and an Aretha Franklin in it. They all have a Donny Hathaway and a Charlie Wilson. I can't really make my voice do that. Even if I did it, even if I was able to do it, then I'd have to compete with the Donny Hathaways and the Charlie Wilsons. The best thing for me to do is be myself and be the best self I can be. My wife and I were just listening to Celine Dion the other day and I was just going, "Holy Moley." That's singing. She's a great singer. You look at the results of her career and you can hear that the force of her voice matches the results of her career.

MR: Ooh. Nice line.

KM: Yeah! [laughs]

MR: You know, maybe sometimes artists can be a little too analytical or critical of their vocals, huh?

KM: That's true, we are. Artists are sitting in the biggest blind spot in the world about their vocals. Because it's you and it's you every day. I'm Keb' Mo' every day. Every time I open my mouth, every time I play, I'm right there. I enjoy it, but it's like you can be a little too inundated with yourself. Maybe the public is listening to other stuff all the time, but you listen to yourself every day. I think the challenge of being a better Keb' Mo', I know my voice sounds different from everyone else's, I know there's a thing that I do that people like, but I don't know what it is. [laughs] It's a kind of a funny thing when you're not a singer-singer. I'm like a Randy Newman. Randy Newman is a great artist, Bob Dylan is a great artist. I think Bob Dylan is a great singer. Bob Dylan's a great singer in my book.

MR: When you look at the "Lay Lady Lay" period with Dylan, it proves he could hit the notes in a song, but he wouldn't do it.

KM: It sets him apart. The way he phrases, the way he delivers the song... To me it's a brilliant vocal.

MR: For me, Blood On The Tracks...maybe Planet Waves...through Slow Train Coming is a great run.

KM: Yeah. I think he progressed at some point past the enduring voice that made him famous. That's the nature and the hazard of being an artist.

MR: I thought he was at the height of his vocal talents in that period.

KM: Yeah.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

KM: It's almost like the same advice I'd have for someone in any business. You're in a new era now. I don't know how old you are, but I'm sixty-two and the whole world that I lived in is gone. Now's the time for creative people. Everyone that's doing well are creating things. They're creating companies. The job thing is over. Now you've got to be a part of a creative thing. I think if you want to be famous as a musician and you want to be successful, you have to create it it in a way that hasn't been done before. You've got your Facebook, you've got your Twitter, you've got your social media, but then you harken back to one thing that never changes: You have to ignite and excite your audience. You can't just go out and go, "Okay, I'm going to try and get some followers on Facebook, I'll get everybody following me on Twitter, maybe if I get on The Ellen Show people will buy my CD." You have to ignite and excite. The very basic thing that motivates everything is word of mouth. If people are excited about something, "You've got to try this chewing gum! Have you tried this chewing gum?" It has to be so good that people have to tell someone else about it. As much as it goes in the future with technology, the more things are like the way they've always been. You have to excite your audience. James Brown excited his audience. You go back and listen to James Brown. James Brown on his death bed was exciting audiences. You look at his films and the work he did: Wow.

MR: I look at artists like Bruno Mars and I think he understands the stage.

KM: He's amazing. Once again, the talent matches.

MR: How do you ignite and excite?

KM: I don't know if I'm exciting and igniting as it were. I'm pretty clear on what I got and what I don't got. What I try to do is create a very warm, ethereal, heartfelt evening and connect. People can come and they go home feeling good after the show. I try to write songs that are good enough that they'll excuse my lack of vocal prowess. Songs that speak. Songs are the deal. However great your voice is, or not great, you still need a song. I go to the common denominator of the whole thing, which is, to me, the song. The melody, the lyrics, the message, the tempo, the accompaniment, the feel, every detail of it I try to really make sure that when people leave, whatever money they spent they felt like they got a really good deal.

MR: I love that. Do you notice any effect you've had on your audience?

KM: Well the audience is a mixed bag. I'm one thing up there. They can look at me or they can look at something on stage but I'm looking at hundreds of people. I wish I was looking at thousands, but I've got hundreds right now. Depending on what face I look at, there's people having all kinds of experiences. Sometimes people are falling asleep. Not because they're bored, but sometimes you see someone bring their girlfriend and maybe their girlfriend's not into Keb' Mo', or maybe the girl is but the guy's not or something and one of them's falling asleep! Other ones might be up dancing, partying, having the time of their life. At that time instead of going, "Oh my god, I'm putting everybody to sleep!" I try to just find someone who's having a really good time.

MR: We talked about BLUESAmericana and your tour with G. Love, what else is up? What mischief are you getting into?

KM: Ooh, mischief, I don't know. I'm trying to get on Bonnaroo. I want to be on the big stage at Bonnaroo. They haven't called me yet and I'm a little miffed about that.

MR: [laughs] You tell them the guy that played Robert Johnson on screen demands it!

KM: [laughs] I'm miffed to the point now where I'm losing sleep over it. It'd be nice. Maybe I'll just have to go and bring my guitar and talk to somebody and say, "Can I do one song in your set?"

MR: That's kind of how it works. You know how to work a room.

KM: Yeah. Basically I just have fun. I try to be really present with the audience, really present in any moment I'm in and just have fun. I'm very grateful for my life and what I'm allowed to do. At the end of the day, that's what it's about.

MR: As I mentioned, you were also an actor. Do you miss it?

KM: I never really tried to be an actor. People would call me to do parts and I would go do them and then somehow people started thinking I was acting. I've never had an acting agent or anything but if someone calls me, I'll go do it. I'm no Robert DeNiro or Meryl Streep or anything like that, but it's fun to do. When I sit in, I get to go and it's fun.

MR: I think if Robert DeNiro made a call to someone who's booking over at Bonnaroo you'd be in in a second.

KM: Yeah! That's what's missing. That's what needs to happen.

MR: You've got your fingers in so many pies.

KM: I've been very fortunate like that, and that's what I'm just being very grateful. I keep trying not to piss anybody off. [laughs]

MR: Yeah, I imagine that's a hard thing to do.

KM: If I ever talked politics, I'd piss a lot of people off.

MR: Well let's test that. What's in the news right now that's bugging you?

KM: The Middle East. I just wish at some point, we would cut our losses and leave and use our own oil. Leave them alone.

MR: It seems we get so close to self-sufficiency as far as energy and then it gets derailed.

KM: It's human nature. I have an agenda. I want to be a musician. I want to sell music. If people start buying video games and start doing different things, I don't get to sell music. It's kind of human nature. We're creatures of habit so they keep doing what they do. That's what they know. They don't know geothermal, they don't know wind, they don't know solar. They know oil. That's such a big old rabbit hole, I don't even know where to jump in. The gun thing with kids going in and shooting up the place... There are any number of issues.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

A Conversation with Richie Kotzen

Mike Ragogna: Richie, whose idea was it to put together a Richie Kotzen Essentials collection?

Richie Kotzen: It really came from the label. I wasn't planning on doing it. I would've done another Winery Dogs record or a solo record or whatever. There's this big demographic of people that come up to me and are like, "Wow, I didn't know you sang." I'm thinking, "Well I've been doing that since I was seventeen but I understand." They're excited and they say, "I want to hear your music, but there's so many records, I don't know where to start." So we decided to make a collection that answered the question, "If I don't have any Richie Kotzen records, where do I start?" Now there's a starting point. That was really the objective of the record.

MR: You've lent your talents to so many other artist's projects. But did you originally focus on a solo career?

RK: That's what I did. I made my first record when I was eighteen. I've always been a solo artist. I got my contract bought by Interscope when I was twenty and I moved to LA to work on my solo career. Unfortunately once I was here after a year of writing and I had Danny Kortchmar lined up to produce my record and write with me, they decided that they didn't want me to make the kind of record that I wanted to make, which would've been a little more like what I'm doing now, combining my influences the way that I do. They wanted me to be more of a hard rock artist. I refused, I didn't make a hard rock record, they dropped me and my career went the way it went. I continued to make records, but first and foremost I am a solo artist, it's what I've always done. I go into the studio and I come out with a record. It's just what I do. I know people who aren't really super familiar with me hang on to the fact that in 1993, I did a record with Poison. I think a lot of people kind of stopped listening or paying attention, but I've always been a solo artist, it's really who I am.

MR: You can understand why they emphasize that, though. You had some big hits with them, like "Stand" and "Until You Suffer Some."

RK: Yeah, yeah. It's definitely not evil that I was part of that, that was a great record that we made. I still stand behind that record. It was a great time in my life. I do understand the perception, but again the idea with this record was to shine a light on what I've been doing for the last fifteen years and also, like I said, give people a launch point if they're curious to get into my music.

MR: That's true. You were also part of Mr. Big, and you had "Change" and "Get A Life," which were both popular.

RK: Yes, that was right after the Mr. Big era that I put that record "Change" out. There were some TV spots in Japan that used those songs.

MR: You've listed Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan as some of your influences. Do you still feel those influences affecting your choices?

RK: Yeah, I do still feel that. I always think that what I do is definitely a product of my environment. I trace it back to when I was a kid. Right around the time when I was learning the guitar, I was around seven and my mom was a real rock fan. She saw Jimi Hendrix, she saw The Beatles when they came over the first time, The Stones, Blood, Sweat & Tears, The Who, all those acts. Those records were played in my house, so there's that classic rock influence that was just constantly in the hallways and through the rooms, I was always hearing it. At the same time, my father was more into the R&B stuff, so Talking Book, the Stevie Wonder record. I kind of have this divide between R&B of that era and rock of that era. I think that kind of defined who I became as a musician. Those are my primary influences. As someone that's been doing music as long as I have I don't necessarily think about influences, I just kind of act upon what I hear in my head. When I have an idea for a song, I work it through and it becomes what it is. I'm not dissecting myself, but if a Curtis Mayfield song or a Who song comes on the radio it brings me back to a certain era in my life. I'm aware of my roots, so to speak, but as far as the act of being a recording artist, when I'm writing a song that's the farthest thing from my mind.

MR: You seem to have a bit of a jazz influence, too, since you've been hanging out with folks like Stanley Clarke.

RK: Well I did do the record with Stanley Clarke and Lenny White and that was a real education. Honestly, I'm surprised that they chose me because I'm not a jazz guy. I don't know any standards, I don't have a lot of history. I appreciate it, I love John Coltrane and Miles Davis, I understand the art form, but I would never call myself a "Jazz Guy." Even in that band, playing with jazz musicians, I was still being me and doing what it is that I do. So apparently, there's an element of my playing that can kind of move into that direction, but it probably is something that comes more from the R&B side of things and definitely not because I studied jazz, because I really didn't. I wish I did. I'm blown away when I hear some of these guys, but I can't claim that I'm a jazz guy.

MR: What is it about your sound, maybe your style, that makes other artists seek you out for their projects?

RK: It's hard to step outside of yourself, but I think there's an honesty that exists in me musically that I discovered as I went through my growth as a musician and also the experiences that I've had in the music business that put me into a position where at some point, I decided, "I'm not going to make music that I don't love, and I'm not going to play songs that I don't love." Creativity comes out of being connected with yourself. If you're doing something that is not really something that you feel good about instinctively, you're going to suffer. I've really created a scenario where I won't do something unless I absolutely believe in it. Even with the Winery Dogs, when we got together, we didn't discuss a direction or anything, we just kind of let it happen naturally, and it worked because we didn't have that pressure on ourselves. I think that kind of approach is healthy because you never find yourself in that position where you're unhappy creatively. I don't ever want to be mad at music. The short answer to your question is there's an element of honesty in what I do. A huge element. I won't do something unless I fully believe it's a part of me and I'm connected to it.

MR: Speaking of being connected to it, are there any songs on this collection that are more essential to you than others?

RK: I don't necessarily go back and relive my past, but I can say that there are songs that I think are really significant, especially a song like "Fooled Again." If I was somebody who'd never heard me before and I wanted to know what I sounded like, I'd probably start with that song. It kind of encompasses all the elements of what I do. Stylistically, it has this Curtis Mayfield kind of vibe, but I'm also singing in my style that I sing in and there's the solo that I pretty much go totally off on. It's an important track for me. There are other tracks on here too... "Remember" is one. A lot of these songs are songs that I always play live. There's reasons for that, I guess. But like I said, I never really analyze it, it's just something where I know which songs really hit home for me.

MR: After listening back to a project like this, does it inspire you to do more solo work?

RK: Uh, not really that. I live in that world all the time. If anything I like taking breaks from myself. It's funny, when the Winery Dogs thing happened I had just come off of an album cycle of my own, a solo record called 24 Hours. We were touring a lot, we were out for about two years on and off. I remember saying to someone, "Before I dive in and make another record, I really want to take a break from myself." I even said, "Maybe I should do a project where I work with some other people and then come back to myself when I'm recharged." No sooner did I say that than I got the phone call that Mike Portnoy and Billy Sheehan were looking to do a power trio and wanted to get together with me. It's funny how stuff works, things just kind of happen the way they're supposed to happen I guess. I don't really analyze and look at it like, "Oh wow, look at this thing that I did," or "Look at these accomplishments," because I'm still in a place where I want to continue grow and do work and move forward. At some point I guess I'm going to get tired and not want to put records out and not want to tour and it'll be nice because then I can look back and have that kind of attitude and say, "Wow, I released a lot of music over my life," but for now I'm excited about what I'm doing today and moving forward with that.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

RK: Musicians ask me--mostly younger guys--"How do I grow, how do I move forward?" A big component to that is playing with other people. Not everybody has to be a great musician, but by playing with other people and interacting with them and really listening, you grow. Even in my solo band, for example, we're obviously playing my music that I wrote and mostly performed on recordings. I pick guys that can elevate this music to a place that excites me so that night after night there's always something different that happens that I pick up on an improvisation level. That keeps me excited. A key thing for young guys is just to get out, play live and play with other people in different styles. Maybe someone's more of a musician and that's not really your thing, but don't be afraid to experience that. That will help you grow. Once you've arrived to a place where you feel like you have your own identity musically, then the parameters are a little different. Then you select people that have more in common with you and that can elevate your music. In the early stages, play with as many different people as you can. Play live. Playing live is a key component. That would be my advice to young artists.

MR: Do you remember what advice you got when you started?

RK: Funnily enough, there's an Ozzy story floating around from one of the interviews that I did; in that time that I spent with Ozzy we were talking about the record business and one thing that he said to me was, "Always pick the money." We were talking about record deals and I was explaining how I had several deals from major labels that went south, and he said, "Here's the thing. People talk. On one hand, you've got a guy telling you that they're going to give you a twenty year career with box sets and everything and then in the other hand you've got someone who seems like they're not interested but they're going to give you a half a million dollars to go and make a record; take the money." That was his advice. It seems like at least in the music business that's the only thing that's concrete. Everyone talks a lot of shit, tells you a lot of things that are going to be happening, but they don't really commit. The only way to force a commitment, at least back in those days, was through a front-loaded deal. That was the advice that Ozzy gave me.

MR: It's the proverbial bird in the hand.

RK: Exactly.

MR: What about your future looking like?

RK: I have a new solo record that's going to be released in January, it's called Cannibals. It's ten new songs. I'm very excited about the record because there's one piece on it that I wrote with my daughter and I can't wait for people to hear it. My daughter's seventeen now, but probably four years ago she was playing this piano piece every time she'd sit at the piano and I said to her, "What is that?" and she said, "Oh, it's something I wrote." I set up the microphones and recorded this and it lived on my hard drive for years. When I was finishing my record I went back to look at some of things I had recorded and I discovered this piece and I just had this idea for lyrics, so wrote lyrics and sang on it. It's one of the coolest things I've done. It's different from what I normally would've done, it's just piano and voice, and because she wrote the changes it's got a whole other vibe. It's really a cool piece of the record.

MR: Is this where your daughter's going?

RK: Yeah, she's really doing well with music. I don't want to jinx anything but she's got some great opportunities in front of her. I'm very excited for her right now.

Transcribed by Galen Hawthorne

photo courtesy Anderson Group

A Conversation with William Pilgrim & The All Grows Up's Ishmael Herring

Mike Ragogna: Ish, you and Jesse Holt joined forces on "In The Streets" for the Blind Boys Of Alabama. First off, relative to the song's topic, please would you go into your history and relationship with Jesse?

Ish Herring: I spent six years on the streets of Los Angeles. Jesse came into a circle of friends I was in. He also came with a really good friend of mine named Joshua Douglas to our "In The Streets" music video shoot, who is also a hugely talented singer songwriter from the street. Within the homeless community, kids come and go. Sometimes they disappear and you never know what happened to them. I hope his appearance at the VMAs can be that opportunity that helps him leave as well.

MR: Were there times during that period when it got so sketchy that you guys weren't quite sure if you would pull through and if so, what kept you and Jesse going through the extreme challenges?

IH: Living on the street, things in fact did get very dangerous for me, but I made it through. I lost some good buddies who were not as lucky. Every day it was a different kind of crazy; someone coming at you with a knife or chasing you out of somewhere you shouldn't be. Oddly, you become addicted to the energy, as crazy as it may be. What kept me going through those situations was hope, as well as close friends who were willing to lift me up from time to time.

MR: Do you feel that the environment is changing in a positive way for those caught in the same situation or system and if not, what needs to be addressed immediately and might you have any suggestions to improve things?

IH: I don't see things on the street changing at all. Youth homelessness is a symptom. Until we deal with the underlying issue of poverty we will continue to feed our children to the street. I grew up in the foster care system, living in boys homes across Kansas. What I saw in myself and in others who ended up on the street is the fact that we were never given the tools to become productive members of society. In the absence of family or healthy role models, we created our own understanding of what it meant to be grown up, and not in a good way. To help kids on the street you are constantly chasing issues like drugs, alcohol, poor parenting and mental illness. To really eliminate youth homelessness, you must tackle economic policy.

MR: You not only participated behind the scenes with the project, but you also wrote the song "In The Streets" that the Blind Boys of Alabama covers. What is it about the song that resonated with the group? Why do you think they may be the best to deliver this message at this time?

IM: Philip Romero and I wrote "In The Street" as a plea for change. What we need right now is a civil rights movement inclusive of all races. One that fights back against the policies of poverty. We couldn't think of anyone better to help deliver that message than the Blind Boys of Alabama. They were a soundtrack of hope during the '60s in the Jim Crow era in the South. It was an honor to work with them.

MR: Jesse appears in the video and helped you with the project. How do you think you both have grown from the experience?

IH: We both have experienced great opportunity as of late. Me with William Pilgrim and Jesse through Miley Cyrus, but there is a lot of undiscovered talent just walking the streets of America without a place to stay or sleep. I hope we are able to bring attention to these invisible people.

MR: What advice do you have for those who find themselves living on the streets?

IH: If you find yourself living on the streets, friends are everything and loneliness will drive you insane. You have to establish a routine that allows you to survive and get food. In an ideal situation, you could just wake up and look for work but when your spirit is broken, substances sound better than responsibility. One must be careful not to fall into this snare, it leads to total destruction.

MR: This is a bit of a non-sequiter but I do ask every professional musician this. What advice do you have for new artists?

IH: My advice for new artists? Be brave and unwavering with your goals. A lot of it is just busting your ass and not giving up before the miracle happens.

MR: Is there any further commitment on yours and Jesse's to helping behind the scenes with causes related to runaways and the homeless?

IH: We started a program called "Write Off The Street." The goal is to help homeless and at-risk youth gain power over their experiences on the street. Many have horrible things bottled up inside. Music can foster a creative and healthy outlet for expression. We give guitar lessons and teach song writing techniques. You would be surprised at the talent that is out there.

MR: Are you hopeful that poverty, abuse and homelessness will be addressed better and if not eliminated, then significantly improved in your lifetime?

IH: I remain hopeful. When the people demand a change as a whole then we will see the birth pangs of what could be change.

A Conversation with Warren Cuccurullo

Mike Ragogna: What was your vision when creating The Master?

Warren Cuccurullo: Initially I thought we'd have my ambient guitar loops and he would sing & play over them. Some lovely relaxing soundscapes with the haunting sound of sarangi. When I saw his reaction to certain acoustic pieces I previewed for him I knew we would have to be developing those. I thought if I could surprise him with something intricate we would have the entire project complete. Some contrast to the free form of the more textural tracks. That's what led to the creation of "4D Suite."

MR: Do you consider Ustad Sultan Khan one of the great masters in music? What resonated most with you about his music?

WC: I believe that, like the great Pandit Ravi Shankar, at any given moment he could've been considered the greatest instrumentalist on the planet. His playing could have me in tears in about three minutes. When he played it went right to my heart.

MR: What are your personal high points of this new album? Are there any performances on The Master that are your favorites perhaps more than other moments on the album or even your past recordings?

WC: When he was recording his parts it was like a concert performance. There were about 9 people in the room and there would be applause after he'd finished. The one that sticks out for me is the take for what would become "The Lost Master." It was glorious, amazing, but he wanted to do another one! We did, & that's the one we used on "4D Suite" but his first performance warranted it's own new track.

MR: Ustad Sultan Khan was considered an Indian music icon and Warren, you've played with icons such as Frank Zappa and Duran Duran. Warren, what are your feelings and observations about your bodies of work and statuses?

WC: We have both been in the presence of very great masters in Frank Zappa for myself and Ravi Shankar for Khansahab. Much is learned from these types on many levels not just musically. I feel we are always responsible in our output to somehow be true to where we came from & to bring the listener back to the original source of inspiration.

MR: Do you have favorite songs or performances from yours and past catalogs?

WC: Some of my current faves would be "US Drag" by Missing Persons, "4D Suite" from The Master, "Be My Icon" by Duran Duran, and "Sid Arthur's Message" from my Playing In Tongues CD.

MR: What advice do you have for new artists?

WC: Be yourself, never compromise, always do your very best, work hard. That's what I did. Not sure if it still works.

MR: What was the best advice you ever received?

WC: Frank Zappa once said to me during a parting embrace "don't spend all your money on scenery." I had just explained our Duran Duran '93 stage set to him.

MR: What does the future bring for Warren Cuccurullo?

WC: I am hoping to connect with Sultan Khan's son Sabir who also plays sarangi & sings. We've been in touch and are discussing the possibility of performing the music of his father & myself. That would be the immediate future.